A while ago, when I was just starting to try and figure out what the holidays meant, I took to scavenging from the bodies of dead traditions to cobble together my own practice. One of the scraps I latched onto seemed like a good fit: mistletoe, a holy plant, something cheerful and foreign and Pagan enough to give my stumbling attempts some credence. It was a part of the holiday I had grown up in, too, although no one in my family was particularly big on it.

Still – kissing and Victorian parties and all that. It would be nice to bring something from the old holiday into my new one. Plus, it would tie the holiday to my patron. What could go wrong?

The plant would have to be real, though, the kind I was sure ancient druids had cut down from its perch for their own holy reasons. I’d never seen it alive, just plastic reproductions in the decor aisle, but I wanted authenticity. I wanted to put some nature in my nature religion. Surely someone would sell it around the holidays for just this reason. I live in a big city. I could afford to shop around.

It took longer than I thought to find a florist that sold it. The plastic clamshell she handed me contained a pale, sickly, and venomous-looking plant. I don’t mean “poisonous” – sure, munching on one of the pus-like berries would do some serious damage to my internal organs, but this thing looked like it wanted to kill me through its own actions. It looked malignant, a creeping, reaching being of ill wishes. I hadn’t known it was possible to dislike a plant instantaneously and with no good reason – but this thing was vile.

That said, it was what I was looking for, and I figured I’d get over this weird gut-level reaction to it. So I took it home.

Mistletoe joined to a tree [J. Engelhardt, Wikimedia Commons, CC 1.0]

It hung on my pegboard, lurking and making its plans, until the rotten-looking berries shriveled and dried. Eventually, when the season ended, I took it down and bagged it up to put with the rest of the magical plants, safe and far away from anything that might touch food. I wanted nothing to do with it – but maybe, sometime, it would be useful.

That was the year I first read Lupa Greenwolf’s books and encountered the idea of plant spirits. Greenwolf is very clear that even after its death a plant or animal is usually still accessible. I could probably speak to this plant itself, but I wasn’t interested in doing that, not really. The spirit of Mistletoe, though, the spirit of all plants like this one, that might be someone worth knowing. At the very least, I figured, they’d be able to offer an explanation for why I hated this sprig of theirs so violently.

I therefore set out on my first real astral trip. I don’t remember how long ago this was, or which apartment I was living in at the time, but I remember my altar: a blond wood dinner tray, covered by a goat skin and with a tiny cauldron for the haphazard fires I would occasionally set. That cauldron would eventually rust from the way I treated it and need to be disposed of, and it was already showing its age then, when I settled down onto the ground and lit my flame, putting the sprig of dried mistletoe next to it as I closed my eyes.

The figure that stepped out to meet me in the wooded clearing was shorter than I was. I read them as masculine, although I knew that didn’t mean anything, and as tending slightly towards a paunch. They seemed wealthy, or at least important – anyone who would wear a doublet of green velvet so dark, with seed pearls scattered across it like stars, would have to be important.

Even before they said anything, I got the impression that I was trying their patience by asking for an audience, and they didn’t like having their time wasted. They stepped closer and, as I bowed, I saw that the pearls on their outfit were small, white berries.

“Thank you for – I just wanted to say hello, and thank you for your time,” I said, stumbling. I knew spirits, of course, but nobody quite like this. I wasn’t sure about the rules. Greenwolf had suggested asking a specific question – what was it? “I wondered if you’d like to work together.”

They laughed, and while it was pleasant, it wasn’t at all kind. “If you want to kill something,” they said, their voice unpleasant in my inner ear, “give me a call.”

“Is that how you want to work with me?” I asked.

“It’s what I do,” they answered, grinning, and raised one hand. I knew their plant was a parasite, and in that same way I knew what I saw on their finger was a poisoner’s ring.

“Thank you for your time,” I said, meticulously polite, and they left me alone.

*

One of my partners tells me about the year ze flirted with Datura, the spirit of the plant also called thornapple or, more colorfully, “devil’s trumpet.” They never made contact directly, or at least were never close enough to touch. Ze showed me the bottle they made of datura’s relatives, all of the nightshades they had around the house, locked in vinegar together to fester and sharpen into an envoy, an invitation. They undertook months of reading, research on the correct preparations, firsthand accounts from people who had partaken of the flower, scientific write-ups of the care and tending of the plant itself. Ze was fascinated.

The risk was too high, in the end. I watched as ze discarded the spell bottle, looking a little uncomfortable with the benign nightshades inside. “Datura would work with me,” ze said. “But I don’t think it’d, uh, benefit me? So I’m gonna let it go.”

Sometimes it takes a while for me to get that message.

*

The year after I spoke to Mistletoe, I tried again to make it a part of my Yule. I was hungry for traditions, and this was something I had done once. The sprig that year was bigger, and I thought it might be happier if I hung it on the Yule tree itself.

It looked like the sound of Mr. Smith’s voice calling human beings a virus in The Matrix.

The partner I live with was firm. “I hate it,” she said, looking at it as though it were a stain on our tree. “What if we didn’t do this, next year?”

I thought of the spirit’s unpleasant smile and nodded. “Fine with me.”

Afterwards, while putting the dried sprig into its bag, I thought back on this. I knew this, I knew it wasn’t pleasant, – the spirit had told me so themself. I knew it was poison. Why had I brought it back in?

I wanted it to work so badly. My patron doesn’t have many images strongly associated with him, but mistletoe, that’s the big one. It’s not exactly the most flattering part of his story, but Loki knows how to take a joke. If I were going to have a winter holiday, I wanted him to be a part of it, and this should have been an easy way to make that happen. Too bad it refused to work.

I now had in my hands another dried piece of poison. I didn’t like discarding magic, even when it made me uncomfortable, but what did that leave for it? The altar, maybe? I considered it – the placement of the sprig, the way it would need to sit – and decided it was a terrible idea. Loki is a multifaceted god, but I don’t often work with the bitter, pained side of him responsible for the mistletoe story. Into the cabinet it went, then. I’d find something better to do with it.

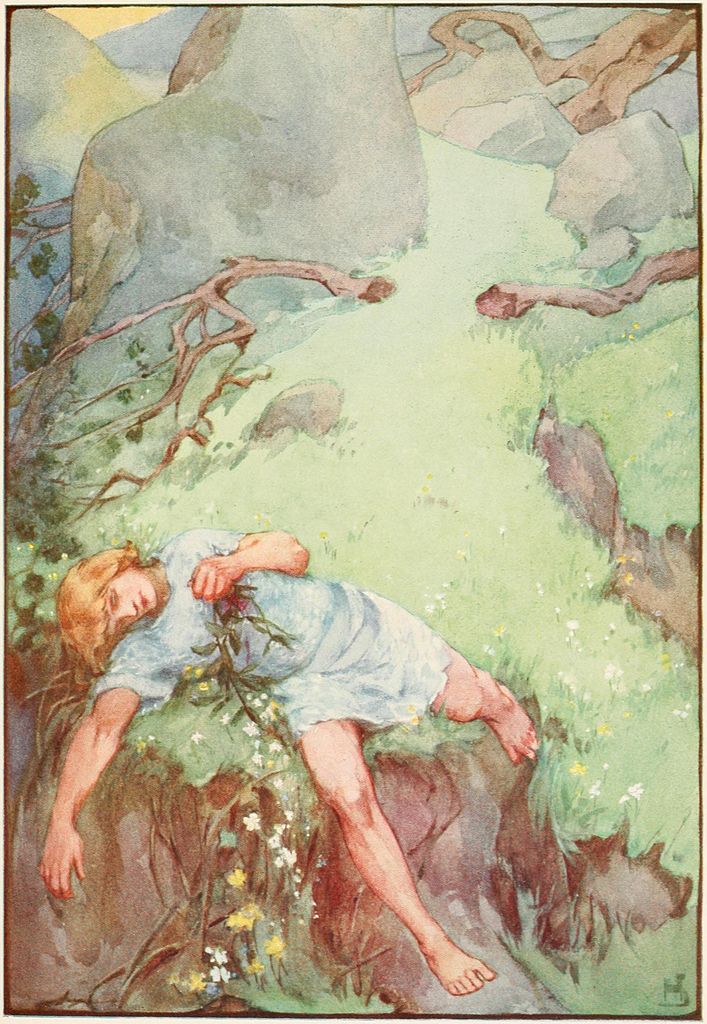

Baldur’s death by mistletoe, from “A Book of Myths” by Jean Lang [Helen Stratton, public domain]

The story is the death of Baldur, as any Heathen knows. As it is usually told, Frigga asks everything in the world to keep her son safe – but she doesn’t bother to ask Mistletoe, because it is so innocent and young that it couldn’t possibly hurt anything. As such things go, it’s the very item used to kill him.

Common knowledge in Heathen circles is that the people telling that tale in Iceland wouldn’t have known anything about mistletoe, except perhaps that it was considered a powerful plant in England. That’s how most scholars make sense of the myth. Mistletoe is a vine, not a tree, and making any sort of projectile out of it would be almost impossible. For me, the paradox was doubled by the idea that anyone could look at it and see anything other than a killing blow.

It seemed like there was a joke I was missing, a nuance to this complicated myth that I wasn’t considering. I’d thought about it a lot over the course of my work with the plant, turning it over in a way that wasn’t quite meditation. I considered the motifs: a beloved child, dead too early; a murder weapon that made no sense; a murderer at a remove; a blameless proxy punished. There are many details in the sequence of events that lead up to Ragnarok I don’t claim to understand. This one felt personal, and it rankled as I went on with other parts of my practice.

My magical apprenticeship started that year. My teacher keeps a neat but busy house, filled with a variety of spirits, and it seemed only polite to introduce myself if I were going to be practicing in their space. I remember packing up my backpack to head over, and choosing gifts for the house spirits, the major allies, and Baldur, my teacher’s patron.

I was just going to bring mead, and in the end that’s all I brought. But as I was decanting some into a small bottle, my eyes fell on the mistletoe, wrapped and faded and waiting for a use. I paused, and the small voice that is sometimes intuition and sometimes the interjection of the divine whispered in my ear. Why not include a leaf? Show him you’re in on the joke, that you’re a Lokean and have a sense of humor and are making a good offering? What else are you going to do with it?

I picked the bag up.

Then I put it down again, quicker than I needed to, and closed the stopper to my offering before I could be swayed. “Sense of humor, sure,” I muttered to myself. “But what if I didn’t anger literally all of the Aesir on my first day?”

Spoilsport, the little voice said, but it sounded fond as it faded.

In the end, I burnt the sprig as an offering. That was the year I carved a wand out of yew, oblivious to the poison covering my jeans and my gloves and a swath of my lawn. I’ve been taught many things, but I don’t know much about plants. That was the end of it, I decided. Good riddance to bad ideas.

The author’s altar, with the imitation mistletoe to the right [L. Babb]

This year, as I was digging through my wrapping paper, I found a wreath of fake mistletoe. I don’t remember exactly where it came from, or why I packed it away there. It isn’t something I’ve used to decorate my home. A gift, perhaps? It’s nothing like the real thing: the leaves are too dark and berries too big and benign. I sat with it for a few moments, and then went in to set it on my altar, which sits next to my Yule tree.

Maybe there’s a moral here, some insight into interacting with a symbol rather than a source, something to do with how things are different in their own contexts. I have no doubt that the plant means many different things, and can exist in ways I haven’t contacted. Maybe it’s something to do with that.

Or maybe I’m just slow to learn my lessons.

The Wild Hunt always welcomes guest submissions. Please send pitches to eric@wildhunt.org.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.