People in my life know that I only travel for a purpose. There are some who take vacations where their goal is to sit on a beach and not have to worry about much besides the flavor of the next margarita. I admire this impulse, but I have never shared it. As with much of my personality, I blame this on my father, who instilled in me that “vacations” were about seeing as much we could with the time and money that we had. We went on the road to see places we had only read about. I’ve never really thought of doing things differently.

As a Pagan, the places I’ve wanted to see have usually been the monuments of Paganisms past, and that was true enough for my visit to Mexico City. I wanted to see the ancient sites of the indigenous religions that surround the metropolis, like Teotihuacan and Tula, and I wanted to see the Mercado de Sonora, the famed “witch market” I had read about on Atlas Obscura. (Reader: the Mercado was fun, but I have to admit I found the selection of positively enormous rabbits for sale at the market more fascinating than any of the putatively “witchy” wares I saw.) But in truth, these places were all additions to my itinerary, decisions made after my companion and I had already set the reservation on our hotel.

You see, I wanted to see the pyramids, but I came to see La Catedral.

No, not the big Catholic cathedral in the Plaza de la Constitución, lovely as it is – I mean Arena México, la Catedral de la lucha libre. The arena is the home base of the world’s oldest professional wrestling promotion, Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre, better known simply as CMLL, which has been running shows in the building since 1956 (and since 1933 in the arena that stood on the site beforehand.) Unlike American professional wrestling promotions, which tend to be peripatetic, CMLL runs multiple shows a week in Arena Mexico, including their primary event, “Super Friday,” which is broadcast around the country. Because CMLL is such an old institution in Mexico, and because the vast majority of the promotion’s famous matches have taken place there, Arena Mexico has achieved a certain religious significance of its own, the heart of the distinctively Mexican approach to the art form called wrestling.

A panorama of Arena México’s interior [Carlos Adampol Galindo, Wikimedia Commons]

Like many children in the late 1990s, I was introduced to professional wrestling through the infamous “Monday Night Wars” between the American WWF and WCW promotions, when performers like “Stone Cold” Steve Austin and Bill Goldberg were lords over an empire of basic cable. But the wrestler I adopted as my own, my personal protagonist, wasn’t one of the main event players; where American wrestling was (and is) dominated by enormous, over-muscled men, the person who caught my eye was a short, wiry Latino man who wore a mask embroidered with wings and crosses.

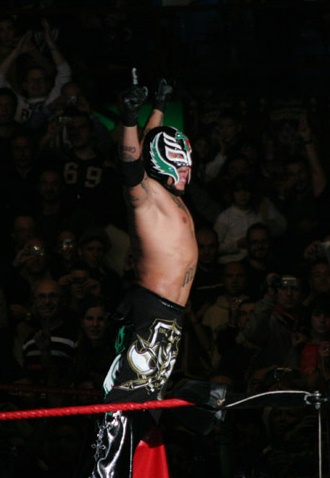

Rey Mysterio Jr. was the standout of WCW’s cruiserweight division, which was famous for showcasing smaller wrestlers who eschewed the heavyweights’ reliance on brawling and feats of physical strength for lightning-quick offense and masterful technical wrestling. Mysterio certainly delivered on those accounts – even my father, less than pleased with my wrestling obsession, had to admit that Mysterio was an incredible performer – but more than his athletics, I loved his persona, his aura, and above all, his mask. The mask made him more than human – it was like watching a superhero, or a demigod.

Rey Mysterio Jr. in 2008 [Wikimedia Commons]

My love for Rey Mysterio led me to find corners of the online world where I could learn more about the lucha libre culture in which he had come up. His mask led to a whole universe of other luchadores, some of whom wore masks of their own. I learned of saintly figures like El Santo and Blue Demon whose names had passed into legend among Mexican wrestling fans. And I learned of Arena Mexico and the whole world it represented, a tradition of wrestling that seemed to my young eyes completely fantastical in comparison to what I watched on Monday nights.

Those early days of the internet were strange, in retrospect; I knew all sorts of things about lucha libre, but because the idea of streaming video was still decades in the future, I never actually saw any of the matches. But that distance only made the idea of lucha libre more tantalizing. The pageantry I saw in my head, legendary struggles between good and evil, all clad in dazzling masquerade, was surely more splendid than anything a real promotion could have feasibly put on.

We had always planned to spend the Friday evening of our trip to Mexico going to see the Super Friday show, but by luck, we happened to be attending the week of the Aniversario, the biggest event of the year, when CMLL celebrates its birthday with a card full of important matches. This year’s main event was a seven-man elimination cage match, where the last person eliminated would have to face the indignity of having his head shaved. (These kinds of stakes are common at major lucha libre shows; the biggest matches often feature the loser giving up their masks or their hair.)

Like any cathedral before one of its high holy days, the grounds outside of Arena México were crushed with parishioners, seventeen thousand people trying to muscle their way inside and to their seats. Vendors called for passersby to stop and examine their stalls full of masks, each of them a token of remembrance for the legends who had passed through the arena before. I bought four, myself, my own mementos of the pilgrimage before my companion grabbed me by the scruff and we made our way inside.

I wandered the halls of Arena México for a moment before I took my seat. There isn’t much to it, to be honest; it is a 1950s concrete stadium, the walls fluted and painted in the colors of the Mexican flag, full of niches where boxes of corn chips are stacked high. It is functional, but not at all ornamented. Unlike a Catholic cathedral, the interior is not meant to bring one to a state of awe in the face of the Christian god; it is meant to efficiently move thousands of people to and from their seats several times a week. But those sorts of utilitarian concerns are not ultimately what makes a place holy.

Atlantis [Alejandro Linares Garcia, Wikimedia Commons]

In the entry foyer, just before the matches were set to begin, a masked wrestler named Atlantis – a legend in his own right who had headlined the Aniversario a few years before despite being in his 50s – stood taking photographs with children. One could imagine similar set-ups reaching back decades, as the crowds of mostly working-class Mexicans poured in for the peculiar mixture of sport, theater, and ritual that is lucha libre.

Above Atlantis’s shoulder, I spotted a shrine on the wall dedicated to the Lady of Guadalupe, something I saw all over Mexico City. I smiled and whispered the goddess a prayer. It seemed only appropriate to do so before entering a cathedral.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.