CHARLOTTE, N.C. –There was a bustling Pagan Pride Day event in the Piedmont region of the Tar Heel state since early this century. It eventually came to be called Piedmont Pagan Pride Day in reference to the name given to the central region of the state. Now, the organizational structure has been dissolved, a lot of money is missing, and there are many people seeking to understand what went wrong and find a way to heal and move forward. To that end several involved have agreed to mediation, but it’s unclear when that might occur, or how the service will be paid for when it does.

The disrupting impact of child porn

While no one has suggested that Druid Scott Holbrook is directly tied to the eventual bankruptcy and dissolution of Piedmont Pagan Pride, his fate is inextricably tied to the events that unfolded later. In late 2016 Holbrook, then a coordinator for Piedmont Pagan Pride, was arrested for disseminating obscenities after sending a nude image of a child, some eight to 10 years old, to an undercover detective. Holbrook eventually entered a no contest plea, but the loss of his leadership position with the local pride organization was one of the immediate consequences of the news.

He allegedly resigned to shield his colleagues from “the difficult situation that had been laid at their feet,” as he said. At the time, he was serving as treasurer.

According to Heather Darnell, who was Holbrook’s predecessor in minding the organization’s purse strings, it was during the transition from herself to Holbrook that the Piedmont name was officially assumed. A new bank account was established at that time, with both Holbrook and then-president Carla Smith having access.

After Holbrook’s resignation, it appears that things started to unravel. New people began stepping into the leadership roles, tensions with vendors and presenters began leading to questions about management of the organization, and eventually it was determined, according to reports, that PPD funds had been quietly siphoned out of the account by Holbrook’s successor, Trilby Grace. Holbrook was responsible for none of this, but it has been argued that his resignation provided the opportunity for the events to come.

A call for religious freedom

Holbrook served on the board with Carla Smith as president and with Christopher Annon in the role of vice president. After his resignation, Holbrook was replaced by Trilby Grace. Annon ended his tenure as vice president after the 2017 PPD event. He then replaced Smith as president in March of 2018.

These several leadership changes happened as cultural changes also occurred.

One of the earliest public outcries took place in September, 2017 in the days leading up to that year’s PPD event. Presenter Mortellus was informed that calling a class “ritual etiquette” would be in violation with an agreement with park staff members, one which apparently had been in place for at least five years.

“Perhaps I’d never have discovered this if not for offering to teach a workshop and having it censored before I’d even emailed a description,” Mortellus wrote at the time, “but it’s out now, and I’m left wondering why we’re doing this.”

As volunteer Cameryn understood the situation, “Basically there was an agreement that Willow from Misfits [Sanctuary, a local business and coven] and a couple of others agreed to that [making] it so that we couldn’t use the terminology we normally would surrounding Pagan rituals and such. We were told by Annon and Misfits that we couldn’t use the word ‘ritual’ to describe our rituals, that we had to use ‘ceremony,’ or a less religious term.”

A call placed to the employees of Kevin Loftin Riverfront Park was all it took to straighten that out; there are no restrictions in park policy or in the PPD contract.

“We found a problem, yelled about it on the internet . . . and then put our heads together to make it better,” Mortellus posted the next day. However, she also observed that Annon, who had disseminated that misunderstanding to pride organizers, was resistant to the change. Of Annon, she wrote that “as the facts came out that this was not in fact a city of Belmont policy – nor had it ever been – he seemed to double down with the notion that this was in fact a state or federal law,” which it is not, she explained.

Discovery of the agreement, which Cameryn described above, led to a public expression of “shock” at the time, according to a statement that Cameryn wrote for the organizational Facebook page and that was soon thereafter removed.

That matter raised other concerns, such as the fact that none of the pride coordinators had a copy of that contract. Mortellus describes Annon as “defensive” when faced with such questions, and “rather a bully,” suggesting that if Mortellus didn’t participate in the event, “it would be for the best.”

Annon initially responded to a request for an interview, but later said that he’d been advised to wait for the planned mediation before making further public comment.

Allegations of bullying and reprisals

Mortellus maintains that there was fallout from her leading the charge to be able to use words such as “ritual” and in the marketing of, and during, Piedmont Pagan Pride. For one, the vendor’s booth run by her cousin was, as she recounts, “moved to the far reaches of the festival” – one that attracted perhaps a hundred different merchants and a couple thousand attendees. Further, the food donations collected there — food drives being a staple of Pagan Pride events — were, reportedly, not counted toward a contest held each year. In Mortellus’ mind, that fact ensured that the contest would be won by the members of Misfit Sanctuary, as is usually the case.

Members of Misfit Sanctuary, including former Piedmont Pagan Pride president Carla Smith, have been heavily involved in the local event, according to Mortellus. A message sent through the Misfit Sanctuary web site seeking comment never received a response.

Cameryn, who started volunteering January, 2017 by organizing the interfaith panel, saw unwelcome changes occur, as she reported, from that point until being “unceremoniously” dismissed from service. In the months leading up to last year’s event, others reportedly stopped pitching in and, as she said, “eventually, my list of responsibilities grew to include coordinating the interfaith panel effectively alone, participating on the first aid team, scheduling/coordinating the classes, reorganizing the website, and more.”

That others were ceasing their work on the event was seemingly a red flag, Cameryn explained. “Piedmont Pagan Pride Day is rife with bullying,” she said. “In the beginning, when I first started helping, I was welcomed. I was told that we needed more people like me. I was ambitious; I was fearless and ready to go. As time went on, more and more people dropped off from the event, as is prone to happen in events that take a year to plan. This meant more burden on fewer people, myself included. I began with the interfaith panel and assisting in first aid, and moved into other areas. I was asked about the website, and when I suggested changes to the organization of the website, after having been told that I was in charge of the online presence, I was bullied by Christopher Annon and several members of the Misfits[sic] Sanctuary, including Carla Smith,” who also serves as national vice president of Pagan Pride Project, Inc., the organization which serves as fiscal sponsor for many pride events.

As an email address for Smith was not immediately available, an attempt to contact her via Facebook was made, but yielded no response.

Much of Cameryn’s frustration came from a lack of communication with local pride leaders. The issue around words such as “ritual” was one such sticking point, but it’s further intimated that neither Annon (overseeing children’s activities) nor Grace (who was organizing the adult class schedule) provided information timely for web updates.

Just prior to last year’s event, Cameryn was out of a job. “I worked on the event, its website, classes, first aid, and other areas, and when I was of no more use to the event, I was kicked from all groups and admin privileges on our online presence with no explanation except a series of messages from [Grace] that really didn’t help anything.”

When public announcements about the serious financial problems facing the organization were finally made last month, others in the community also brought forth allegations of bullying, particularly fingering Annon, now the president, as the culprit.

Mortellus places much of the bullying culture in Annon’s lap, saying that he exerted that negative pressure on all the coordinators, and that she fears for the impact on the pride event in Greenville, South Carolina, with which he is now involved.

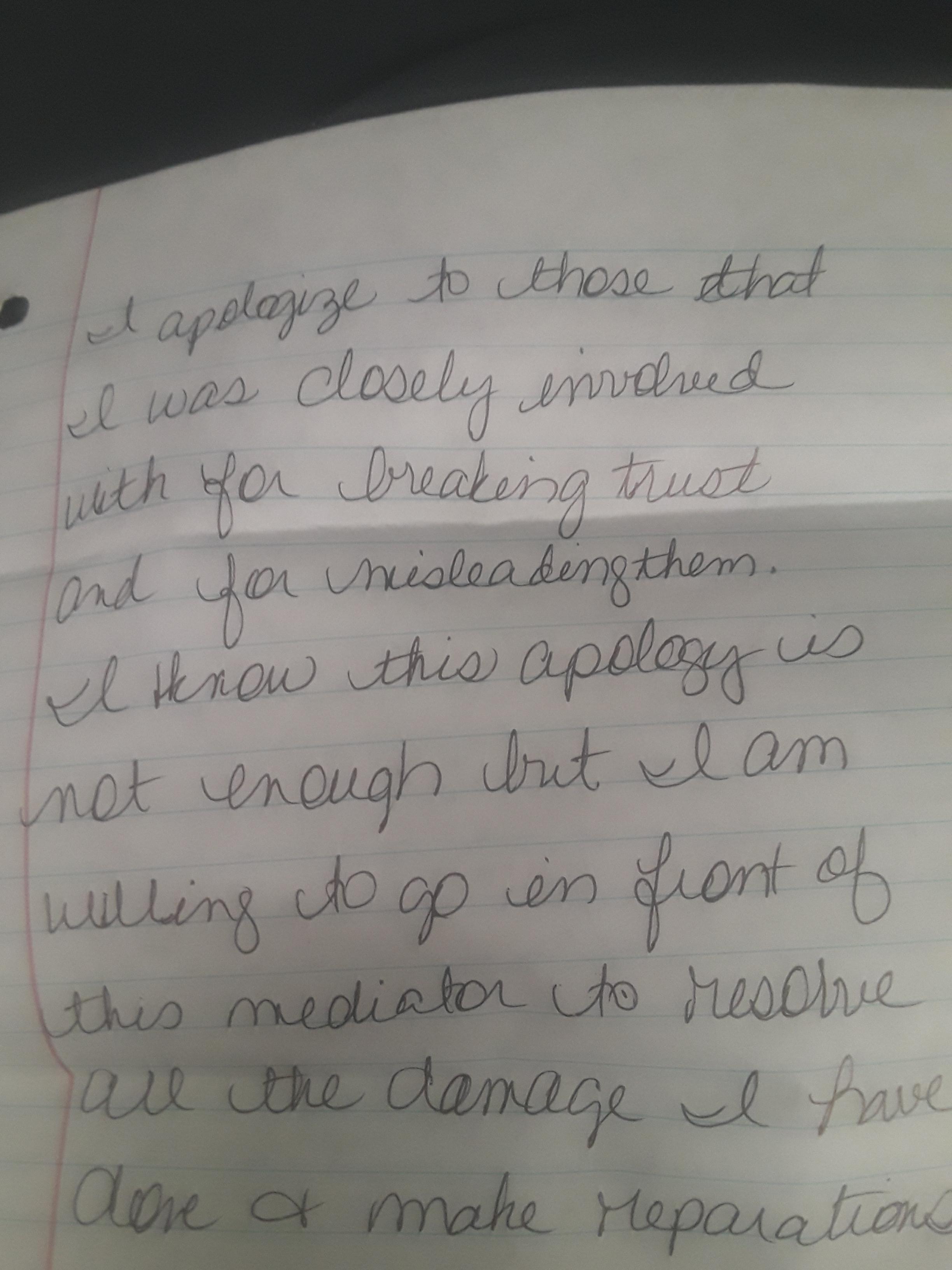

When he eventually resigned his post at the end of May, Annon wrote in part, “I am guilty of speaking harshly to former board members and volunteers in such a tone that could have been construded[sic] as bullying. I am guilty of breaking the trust given to me by my friends, family and my community.”

Later, in what he said would be his final public comment prior to mediation, Annon acknowledged some responsibility, writing that “those people will be heard and a reasonable compromise will be met. . . . I would be glad to meet with anyone I hurt . . . on neutral and safe ground and I will listen. Then we can talk and come to an agreement. Again, did I do things wrong, yes! Am I the monster that a lot of you think I am, not even close.”

Questions emerge about money

“I had my suspicions of foul play around July, when [Grace] wouldn’t produce the financial records,” wrote Cameryn. “I asked if she needed help with accounting, and she said no. I know that there are numerous others who offered the same. She refused to provide the records, so when I heard about the missing funds after I had been removed from PPD, I was not surprised.” Cameryn was told “that it wasn’t my concern because I wasn’t an officer or a local coordinator.”

Mortellus said that she had her own concerns following the religious freedom dust-up and, following the 2017 event, she reportedly discovered that PPD leaders were raising questions about the finances. They not only allegedly couldn’t get bank statements out of their treasurer, they now also couldn’t make important organizational purchases. She said that she fired off an email to Pagan Pride Project leadership, inquiring into copies of financial documents and also asking about what she termed the “erasure” of Pagan terms from the event.

“I got a rather rude reply from Johnson Davis,” the PPP coordinator for the southern region of the U.S., “telling me that I could start my own Pagan Pride Day.” Davis, Mortellus asserts, is friends with Annon.

Cameryn said that she also reached out to Davis, after being removed as a volunteer, “and let him know in late September [2017] that there were likely some financial irregularities that would need to be looked into. I believe my claims fell on deaf ears, as it was apparently not investigated for some months after.”

Davis was also invited to comment for this story, and like Annon, declined to do so until mediation is complete.

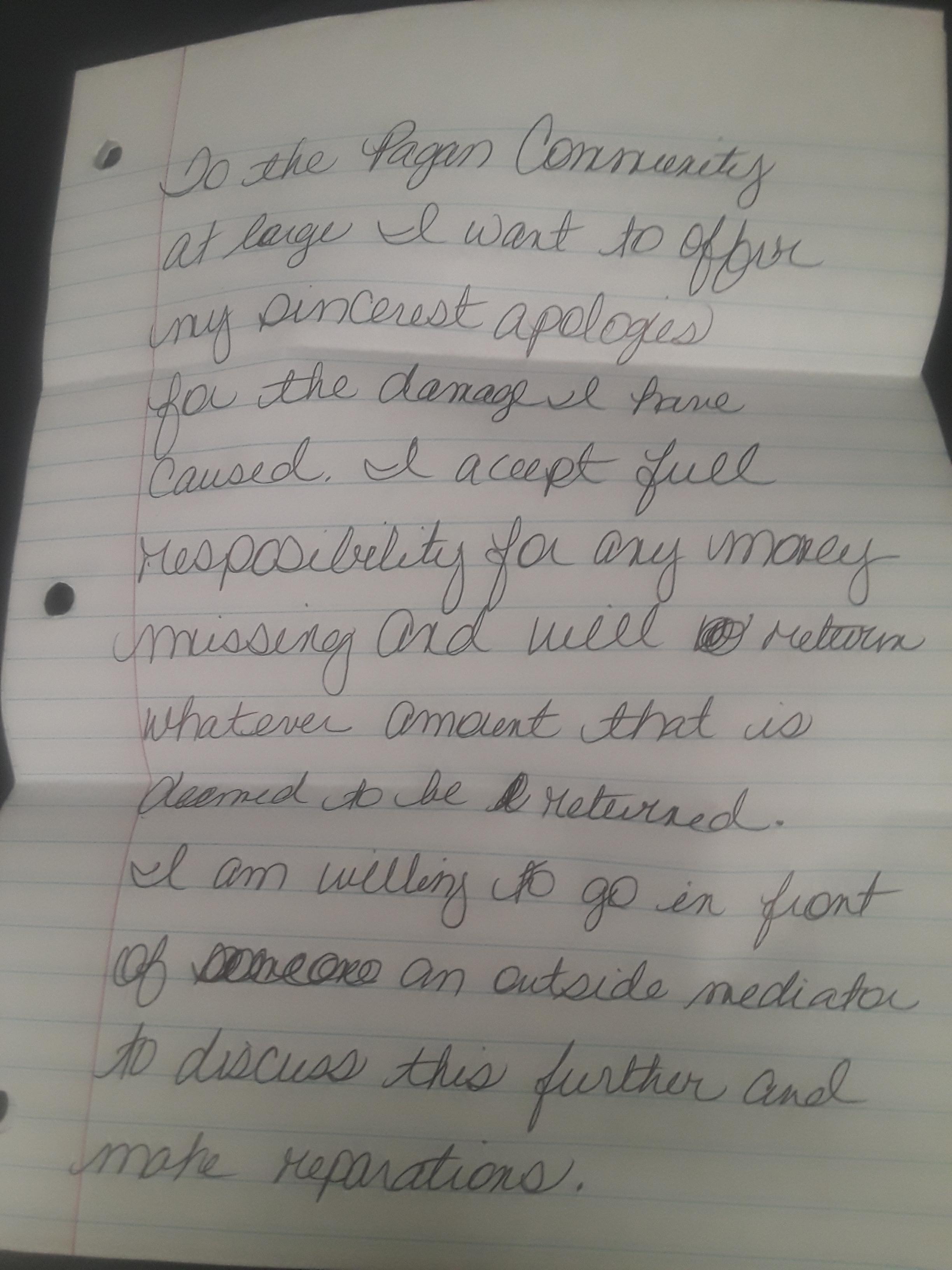

As for the money, it eventually came out that Grace reportedly has been using the Piedmont Pagan Pride account for personal purchases, but Mortellus and others who later came together to investigate that specific situation believe that Smith, in particular, should have been aware as early as October of last year, when the insufficient funds notices started getting generated. Mortellus characterizes Smith’s inaction a “grievous oversight.”

Grace initially attempted to place blame for the questionable transactions — Amazon purchases, pizza dinners, and other clearly personal purchases — on her son, claiming he had taken the debit card. However, there was no record that any of those charges were ever disputed. Later, Grace provided “something of a written confession,” which has been obtained by the Wild Hunt.

Later it would come out that Brian Ewing, president of the national Pagan Pride Project, had counseled Annon to handle the matter internally, and that in similar incidents, “chapters had simply swept the incidents under the rug.” It’s not clear if that wording was selected by those investigating after the fact, or if it was used by Annon himself to describe the conversation.

The public revelations about Piedmont Pagan Pride did not begin until May 30, nine months after Cameryn raised initial questions, and it escalated quickly. In just four posts over two days, the misappropriation of funds was revealed, an explanation as to why Grace would not be prosecuted was posted, a promise to rebuild was made, then finally Annon announced both his resignation and dissolution of the organization.

“I am guilty of give[sic] our treasurer a chance to redeem themself[sic] and not press criminal charges over stupid decisions,” he wrote. “With this being said, affective[sic] immediately, I am stepping down as president of Piedmont Pagan Pride. Our charter will be given back to Pagan Pride national as well as any money left over after refunding our vendors. They will also receive any paperwork available.”

Recrimination and investigation

Community reaction to the cancellation of what had become a beloved event was swift and sure. In addition to the inevitable questions about how and why the treasurer was able to get away with using PPD funds for well over a year, there were comments from those infuriated by what they saw as a coverup.

As Mortellus had concerns about the event management prior to this announcement, concerns which had been shared with other community leaders, it wasn’t difficult to cobble together a group of Pagan leaders in the area who decided to conduct their own investigation into the matter. They included, in addition to Mortellus, Tony Brown (first coordinator of this event), several PPD volunteers and supporters, and Carla Smith, among other community leaders. Dissatisfied with Annon’s explanation that an investigation into Grace’s actions had taken months, yet she was not to be charged in part due to counsel from Pagan Pride Project officers, led them to dig in and try to figure out what had occurred.

The result was a statement of preliminary findings posted on a new Facebook page entitled Piedmont Pagan Pride postmortem information.

First was that there were numerous reports of “verbal abuse and intimidation” of volunteers by Annon, which “led to confusion, stress, and general loss of organizational cohesiveness resulting in greatly reduced effectiveness during the run up to the September 2017 PPD event and culminating in the loss of multiple active team members.”

Grace was implicated as stealing somewhere from $800 to $2,000, although Mortellus said she suspects it may have been a good deal more, as it appeared that cash deposits were never made. During that period she reportedly withheld bank records from other organizers, but, as Mortellus said, “notifications of overdrafts from the bank eventually brought the situation to light in October 2017.”

While it’s not clear when Annon became aware of the problem (Smith having been president when the overdraft notices were first issued), Mortellus said that “[Annon] took no corrective action for several months and instead appeared to engage in obfuscation in order to withhold information about the problem from interested parties in the community.”

Moreover, she added, “Efforts by others, both within and outside of Piedmont Pagan Pride, to engage the national organization on the matter proved unfruitful as several contact attempts were made and met with no response.”

As noted by several parties, there is a plan to conduct some sort of mediation, but when and if that will occur is not at all clear. “It is not scheduled yet,” said Brown. “We’re looking at a few possible agencies and getting ideas about pricing and such. . . . As far as I know, both the president and the treasurer have agreed to participate, but that might change once we start deciding how the process might be paid for.”

Brown noted that the “bargain price” will likely be at least $160 an hour, and added, “I’d be very surprised if it could be settled in less than three hours.”

If it ever comes to pass, the structure is expected to involve a group of community representatives — none of whom has yet been selected — engaging in separate sessions with Annon and Grace.

Another task this ad-hoc committee — sometimes called a “council” — assigned itself was actually getting some money back to vendors, fees paid for an event that never occurred. Annon had reportedly promised it, but Mortellus said that trying to wrest PayPal credentials from former officers was challenging.

Annon has stated publicly that he became aware of the financial issues only in May, two months after assuming office as president, as he didn’t have bank account access prior. He further maintains that the results of the PPD board investigation were posted as soon as they were finalized.

When questions were raised in that thread about Smith’s culpability as Annon’s predecessor, she asserted that neither Grace, nor Holbrook before her, “filed financial reports or ever produced bank statements,” and that those bank statements handed over to Holbrook by his predecessor, Heather Darnell, were “never disclosed” to Piedmont Pagan Pride board members.

Postmortem ad-hoc committee member Gabriella Laughingbrook noted that the scope of their inquiry did not include Smith’s tenure as president.

Implications regarding Pagan Pride Project, Inc.

It may be inferred — and has been, by some of those reacting on Facebook — that PPP officers were in some way complicit with Annon’s alleged bullying behavior, and perhaps even Grace’s financial misappropriation. What’s clear is that the national officers have strong ties to this particular event: Smith, former Piedmont president, is listed as the PPP vice president (although some sources indicate she has stepped down); Johnson Davis, southern regional coordinator, was in contact with several people with concerns about the local event. Both Smith and Davis are described as being friends of Annon.

Tony Brown observed, “The number of people who were not surprised by [PPP leaders’] reaction has really surprised me. I remember them being aloof and maybe a little unorganized, but I never suspected they were so dysfunctional. I think that any PPD that succeeds must do so primarily by luck. I know that PPD events pop up and then disappear all the time, and now I’m starting to wonder what patterns might emerge if they were all really looked into.”

Pagan Pride Project president Brian Ewing was provided with a series of ten questions, but responded with only this statement: “The Pagan Pride Project takes seriously all incidents of missing funds. This is a rare occurrence, which has never occurred at the national level. When the missing funds can be traced to a specific person, a decision has to be made between the local chapter and the national president whether to take further action. This decision is based on, among other things: the amount of money missing, the degree of culpability of the person responsible for the missing funds, and the cost, in time and money, of potential efforts to regain the funds or pursue other legal action.”

Davis chose to chime in on the postmortem findings thread on Facebook, observing, “To my knowledge, no case like this has ever been ‘swept under the rug.’ I think the recommendation was to first try to handle this internally. At least one previous situation at another event was handled that way, with the funds recovered, resignations accepted, and the reputations of PPD, the local event and all parties involved fundamentally intact.” All parties presumably includes those identified as stealing from the organization; however, as noted previously, Davis declined to answer Wild Hunt questions, citing the pending mediation.

Said mediation is not anticipated to include any national officers.

It is presently unknown if, as Brown wondered, other PPD events have faced personality or legal difficulties such as those purportedly attempted to be “swept under the rug” in North Carolina.

On the other hand, Witches and others have been known to observe that “a new broom sweeps clean.” North Carolina Pagans seem poised to make a clean sweep and begin anew, but with lessons learned there’s no guarantee that they will seek any support from Pagan Pride Project for the next chapter in expressing their local pride.

We will report back with more as the story develops.

Edits

- July 12, 2018, 10:30 EDT: corrected name of South Caroline city to Greenville.

- July 16, 2018, 12:50 EDT: changed references to one source to more accurately reflect requested preferred name usage.

- July 17, 2018, 19:47 EDT: removed the word “Pagan” as an example of a word which purportedly could not be used in marketing the Piedmont Pagan Pride Day; clarified the history of the usage arrangement by providing a link.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.