When you die a pagan, roll +versed or +3 if you died in a fight or battle. On a hit your name lives on, affecting those that come after you. Create a token through which your memory survives: a poem, a story, a family heirloom, a runic inscription or something similar. On 10+ you gain 3 bonds, on 7-9 gain one. Spend these bonds at any time to influence those that know your memory.

-Gregor Vuga, Sagas of the Icelanders

Your author is always willing to throw the rune-carved bones.

I have played roleplaying games since I was a child, my activities peaking in college, where, alas, at one point I scheduled myself to play a different campaign every day of the week – and literally twice on Sundays. Although my time to play has diminished over the years, I retain a deep fondness for the art form and all its fascinating twists. No other form, for my money, gets deeper into ideas of identity and performance than a roleplaying game conducted purposefully: in a film we may see a character and sympathize with their actions, and in a novel we may listen in on a character’s interior monologue and discover how that character’s mind works. But in a roleplaying game, the player, who is also actor and author, actually shifts her conscious thought into a different mode of being and makes her decisions according to the preferences and abilities of a character who may have almost no resemblance to her usual personality. As the game designer Robin Laws said, “A roleplaying game is the only genre where the audience and the author are the same person.” So too is it the only genre where the audience identifies so closely with the protagonist, one becomes entirely subsumed by the other.

Because of this, roleplaying games also allow for fascinating experiments in religion. I have attended (for instance) Catholic church services before; I find them uncomfortable, because I am Pagan and everything about those services reminds me of the gulf between me and the congregation. Despite their frequent beauty I can only stand to be in those spaces for so long. But within the context of a roleplaying game I can assume a Catholic persona and attempt to act as that character would act; I am presented with the opportunity first to develop a theory of mind that matches the fictional biography of the character, and then to think according to the precepts of that theory. I understand that this theory must necessarily be incomplete, for I lack the lifetime of experience that informs an actual Catholic’s life and belief. But within the game, I can try my best to act according to the theory of the character I have developed – and from experience, I can say this: when it works, it can lead to what I can only call an epiphany of empathy.

Recently I have become interested in games that model, more or less realistically, other historical periods, and especially periods where old pagan religions were dominant. (This is a niche within a niche, of course: most roleplaying games encourage the play of sorcerers, vampires[1], and space marines, rather than historical personae.) This interests me for two reasons: one, because of the opportunity to inhabit a historical mindset and attempt to act within the bounds of what we know of historical pagan religions; and two, because I am fascinated by how games encourage these personae through their rules. Since actions in roleplaying games are mediated through rules (and, usually, through the game masters who interpret those rules), the rules themselves provide a document of the author’s own interpretation of history and attempts to incentivize players to act in accordance with that interpretation.

The game on my mind at the moment is Gregor Vuga’s Sagas of the Icelanders, a game meant to adapt, well, the sagas of the Icelanders, and more broadly the mid-9th century Icelandic society. Iceland has just finished its initial settlement period, and the Icelanders confront a number of drastic evolutions in their culture. Vuga’s Sagas tackles, through its mechanics, gender roles, societal in- and out-groups, legal affairs, and even family legacies – and, of course, it handles religion, as well.

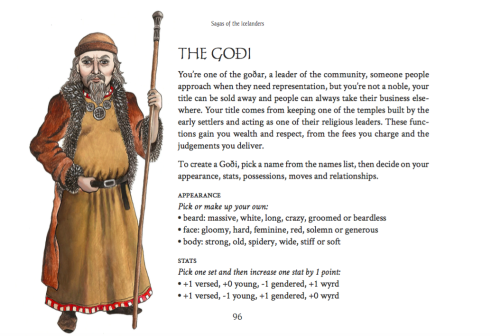

The first page of the Goði rolebook. Art by Eva Mlinar.

In the course of play, players develop a character from a selection of archetypes, including the baseline characters of The Man and The Woman, who represent the common free farmers of the island; The Goði, a powerful (male) lawyer-priest; The Seiðkona, a wise woman with gifts of divination and sorcery; The Huscarl, a man-at-arms in service to a goði; and many others. These characters have access to a variety of “moves” that trigger at certain points in the narrative.[2] The quote at the beginning of this piece, when you die a pagan, is one such move. Some are basic narrative elements: when you tempt fate, when you look into someone’s heart, when you goad a man to action. Others, however, are more specific, and some specifically model the characters’ religious lives. Here is a move from The Goði playbook:

Rites: You can convert your and other people’s possessions into sacrifice. Hold sacrifice equal to their level in silver. While conducting a rite you can spend sacrifice, 1-for-1 to:

- gain a bond with the gods

- give the gods a bond with you

- make it disappear and fill your coffers with an equal level of silver

Here the move presents the player with options about how their character interacts with the religious ceremony. The Goði’s sacrifice can potentially create a legitimate connection between himself and his gods: a “bond” is a kind of relationship currency that the parties can “spend” to influence one another, so a Goði who has a bond with (say) Óðinn can spend that bond to ask Óðinn for a favor. But a Goði is just as capable of ignoring the connection to the divine altogether and using the “sacrifices” provided by his followers to line his own wallet. The character’s religiosity can be either sincere or for show, depending on how the player conceives of the character’s attitude.

Historically, of course, Iceland adopted Christianity (supposedly after a meditative vision by the Lawspeaker Þorgeir Þorkellson at the Alþing in the year 1000). The game models this as well, with the moves when you accept the gospel of the White Christ and when you preach the gospel of the White Christ to an audience, a move which allows the player to convert other characters to Christianity. The mechanics end up emphasizing the inevitability of Christianity – there is no counter-move to encourage the Icelanders to remain with their Heathen gods – though the book also says that part of the point of the game is to work through whether the players’ Iceland turns out like the historical Iceland, or if they end up following a different path.

As a Heathen, the premise of Vuga’s Sagas of the Icelanders is immensely intriguing. The question of how well we can truly know the mindset of the ancient forbears of Ásatrú remains a prominent one in Heathen circles. While Vuga’s game is not perfect (some moves will raise the hackles of the stickler for historical accuracy), I appreciate the offers it makes to me as both a player and a Pagan: the chance to wander for a while in the mind of a medieval Heathen, and the chance to consider my own attitudes towards the past while playing.

* * *

[1] Perhaps I should have mentioned my that the Catholic character above was a vampire? My apologies to Anne Rice.

[2] Sagas of the Icelanders is based off a game engine, conceptually similar to a video game engine, called Powered by the Apocalypse; all games in this family use the “triggered move” system.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

“within the context of a roleplaying game I can assume a Catholic persona and attempt to act as that character would act.”

As a “recovering Catholic” who attended Catholic school for 12 years, came within 1 inch of going into a cloistered monastery (yes, they’re called monasteries, not nunneries) I have to dispute this statement. Unless you grew up in a Catholic household, and had a fairly religious family, you wouldn’t have a clue as to how to “act as that character would act”, no more than you would be able to act as a Muslim, or a Buddhist, or a Hindu. It’s +not+ just about religion, but about the +culture+ that is a direct consequence of the religious beliefs. Even if you “convert” as an adult, you still would be missing certain experiences that only come from growing up in that “culture”. This is true not only of religious experiences, but culture in general. That is probably why people tend to get annoyed with folks who try to “imitate” certain cultures.

It’s easy to emulate a Catholic. Just be a Nazi without the uniform.

All the top Nazis were devout Christians.

Hitler had no interest in ancient Pagan religions. That was Himmler. Himmler’s interests only went so far. He still spoke frequently about Christianity. The Nazis believed Jesus was not a Jew but was the first Aryan.

Hitler was devoutly Catholic and Christian. But he wanted the church subordinate to that state. Both the Catholics and Protestants were all too happy to oblige him with a few minor exceptions. The photos speak eloquently for themselves regarding that.

Nazis artifacts were frequently covered with Christian iconography as well.

The Nazi war against the Jews was the result of many hundred years of Catholic and Protestant anti-Semitic indoctrination in Europe. The Nazis nearly achieved both major branches of the Christian churches goal of the eradication of the Jews and Judaism.

There’s a reason why the Catholic Church was so instrumental in the escape of so many Nazis from Europe in order for them to escape justice.

http://www.nobeliefs.com/hitler.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/speeches.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/henchmen.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/hitlerchristian.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/ChurchesWWII.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/nazis.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/mementoes.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/HitlerBible.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/HitlerSources.htm

http://www.nobeliefs.com/hitler-myths.htm

How is this any different than having to deal with all the Folkish and Theodish nutters who like to pretend it’s still a thousand years ago? These are the cretins that embarrass those of us who are grown-ups and accept the fact we live in the real world? Heathenry’s equivalent of the Westboro Baptists.

I’ll pass on role playing it as well as having to deal with them in real life. I’m an Asatru Modernist. I live in 2016 and have no problem with that. The people who the Folkish and the Theodish seek to imitate are the losers of history. They failed our gods and surrendered the worship of them and eventually surrendered their freedom. They have nothing to offer us but to show us how to utterly and completely fail our Gods and surrender their worship for a second time. The only person who’s a bigger loser is someone who seeks to emulate a loser. The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.