SAUGERTIES, NY — Robert Place didn’t set out to be a tarot artist and scholar. Once upon a time, he made jewelry, including the wedding ring worn by Margot Adler. Through a series of messages and signs he received from his patron deity Hermes, Place set aside that work and turned his artistic abilities to the creation of cards for divination, including tarot. Along the way, he became an expert in the history of how cards have been used for oracular purposes.

Place’s best-selling work thus far has been the Alchemical Tarot, but he has created several other decks in that style, as well as writing a treatise on the subject, called The Tarot: History, Symbolism, and Divination. He’s also explored other divinatory card traditions, such as Lenormand; his newest project, the Hermes Playing Card Oracle, is named for his card-publishing company, as well as the two activities its creator designed the deck to be used for.

Over lunch one autumn day in the Hudson Valley, Place spoke to The Wild Hunt about his work and scholarship, which have become his life’s journey.

Robert Place [Courtesy Photo]

In his dream, Place accepted the call, and was advised that he had an inheritance from an ancestor coming. “They asked me if I would accept it, but warned me that there was certain karmic debt associated with it, but it had a lot of power. I remember thinking, ‘How can I resist this?'” he recalled. “They wouldn’t tell me what it was, only that it was going to come in a box from England, and is referred to as, ‘the key.’ It was so vivid that I woke up the next morning expecting the box at the foot of the bed.”

The box actually arrived with a friend, someone who wanted to show him a tarot deck he’d just purchased, the Smith-Waite deck. Although this deck is more commonly called the Rider-Waite, Place names it Smith-Waite, which comes from long years of research into tarot. First published in England in 1909 (by the Rider Company) and first introduced into the United States, the deck was conceived by the mystic and academic A. E. Waite, but drawn by Pamela Colman Smith, who followed Waite’s instructions. Smith’s illustrations, by which the deck is instantly recognizable to so many, were given no credit in the name settled upon by U.S. Games when it acquired the stateside rights in the 1960s. “Scholars call it the Smith-Waite deck, because Pamela Colman Smith designed it,” Place explained.

Nevertheless, his friend arrived with this English-born treasure, and Place felt a compulsion on him. “I remembered the deck from college,” he said. “I realized that the trumps were called ‘keys,’ and that even the instruction book was called, ‘The Key to the Tarot.’ I decided I had to buy one of these decks.”

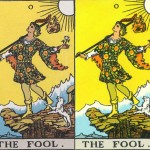

1909 original (left) and 1971 revisions (right) of the Rider-Waite tarot.

Buying tarot decks today is as easy as an internet search can be, but this was before Amazon was a glimmer in Jeff Bezos’ eye. There was no internet, and the closest metaphysical shop to Place’s home on the New Jersey-Pennsylvania border was in Manhattan, close to a hundred miles one way. However, that’s exactly where he went and what he did.

Not long afte,r he was contacted by another of his friends, an astrologist named Ed. “He told me he had a deck [that] he had a feeling I was supposed to have,” Place said, a Tarot de Marseille, the traditional French deck that popularized tarot throughout the world. “I was never a writer, but I started making notebooks,” as he learned about the decks. Books, too, began piling high in his studio: volumes on Gnosticism and alchemy in particular.

From those, he started to see connections. The World card, in particular, struck a chord: “It opened a door in my mind, and images were flying out. Alchemical images, and how they related to tarot cards. I got out my psychology and alchemy books by Jung, to look at the images. I wasn’t sure what to do with it. I was taking notes, and I would tell anyone about it who I could corner. Then it dawned on me to write it down, rather than accost people at parties with what I’d learned. Eventually, my friends asked me why I didn’t just design this deck already. ‘After all, you’re an artist,’ they said.'”

Place continued to have weird moments of synchronicity. He found a magazine called Gnosis, which he read cover to cover. He recalled, “Then, in the back of my mind, I got the idea to send in the Star card I’d already done since they were doing an issue on tarot.” When he did so, the editor called him. They had no plans for a tarot issue, despite the idea planted in his head, but could use the drawing as an illustration for an article on Sophia in an upcoming issue on the goddess. That led to a request to illustrate a tarot book by Rosemary Ellen Guiley, and further work as a ghost writer for her on alchemy, all while continuing to work full-time as a jeweler.

Finally, Guiley asked about his tarot deck. “I told her it was going slow, and she said that I needed a contract, with an advance,” and opened doors for him. That led to the Alchemical Tarot, which is still Place’s best-selling deck, in part because problems with the publisher led people to believe it was out of print long before it actually was, and the demand grew. “When I saw that thirty-dollar deck sell for $2,017 on Ebay, I decided to get the rights back, and publish it myself,” he said.

Priestess from the Alchemical Tarot

This also allowed him to correct problems he’d had with some of the creative decisions, like having to replace the original Lovers card — which showed the act quite clearly — with a chaste version depicting the couple simply kissing. Later editions have both cards, representing different aspects of love energy. He’s put out three editions himself, in runs of 1,500 or 2,000, as well as art copies which are printed on rag paper, signed by the artist, and packaged in a decorative box.

While he hadn’t set out to create a tarot deck, much less several, Place had always had a deep appreciation for art history and used that in his research. To his surprise, “All of the books on tarot were nonsense. They said things like it came from ancient Egypt, but they didn’t have paper. Some people said that things were in the primary sources that, when I finally got translations, just weren’t there.” Scholars like Michael Dummett have since raised the quality of the literature, but Place’s early research eventually led him to lecture about tarot at the NY Open Center, where he taught about its real history.

In short, the earliest known decks, Mamluk cards, found their way to Spain from Islamic sources in the 1300s. Even those first examples often included Arabic calligraphy that included divinatory meanings, suggesting that cards were used for games and divination from the get-go. Once they reached the Italian city-states, some artists added a fifth suit, the carte de triomphe, or “triumphant march” in the tradition of the Caesars returning victorious. Such parades would be organized from the least important captured soldiers all the way up to the winning army’s leaders; likewise, these cards would be ordered so that each one trumped the card preceding it.

Originally they had neither names nor numbers; the order of the trumps varied based on local preference, and all the users knew each card by sight. Once these five-suit decks made it as far as France, users unfamiliar with the images needed names for identification, and numbers so as to order them correctly. The carte de triomphe become tarocchi, and “tarot” in French.

The Smith-Waite deck was based on the Tarot de Marseille, and its wide distribution gave the sense that, not only was tarot the only type of card deck used for divination, but that the suits and trumps were standardized, which they never had been. In fact, that deck switched the order of Strength and Justice, to fit with a belief that astrological symbolism was secreted in the original tarot. Place has seen much older decks, such as one of 40 trumps that was made in Florence, which discredits that theory. He said, “It’s got astrological symbols all through it. That wasn’t considered esoteric knowledge. If they’d wanted to use astrology, they would have; the artists at the time were just more familiar with mysticism.”

Place also knows that tarot was also not intended as an alchemical tool either, despite how well the system fits. Creating a Buddha tarot was surprisingly easy once Place saw that the three groupings of seven cards each within the major arcana (not counting the Fool) paralleled the periods of Gautama’s development.

Some decks were created simply because he was hired to do so. “They were using angels to sell shoes in the 1990s,” Place joked about why he did the Angel deck in six short months. But other decks were works of love, such as the Sevenfold Mysteries, which he developed over ten years.

His research also made him realize that tarot was almost nonexistent through much of the history of cards, while the four-suit Lenormand decks were commonplace for divination. In addition to painstakingly recreating one of those decks in what he imagined was the original, vibrant color, Place collaborated with reader Rachel Pollack to create an entirely new one, the Serpent Oracle deck.

With Lenormand, an image was added to each of the 36 cards, and the deck could be used for games or the telling of fortunes. There were no two, threes, fours, or fives, hence the small number of cards. With Place’s most recent project, he took that idea and expanded it for the modern 52-card deck, by adding other traditional imagery to fill in where the Lenormand decks didn’t have cards. He’d already had experience with such adaptations in the Serpent Oracle deck, which included dimensions not contemplated in the original Lenormand. For example, as Place explained, in many versions of Lenormand, “The aces of hearts and spades were significators, a woman and a man, and you’d do the reading in relation to the appropriate one. We added a second man and woman, so the relationships could be more dynamic, as well as a god and goddess to represent a higher level.”

He’d originally planned on calling this latest project the “Playing Card Oracle Deck,” but that wasn’t very descriptive, so he went back to the beginning, and named it after Hermes. That’s the name of the publishing company that he created to keep his cards and books in print. And that is the name he came in time to realize, of the voice which had nudged him onto this path in the first place. “He almost always talks to me in dreams, and he’ll lie to get me to do the right thing,” Place said. “I go to Pagan events, but I don’t really fit in with other covens or groups. I’m just a spokesperson for Hermes.”

The Hermes playing card oracle is currently being funded on Indiegogo.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I was also told, once upon a time, that tarot was in fact the Egyptian Book of the Dead in pictures. Enjoyed his book on tarot origins and this interview.

Just a note: it’s the Burning Serpent Oracle deck that he did with Rachel Pollack–and it is beautiful.

The Tarot trumps are a sampling from a much larger range of symbolic figures who appear as motifs in Renaissance art. Court entertainments were typically tableaux, ballets, operas or plays representing elaborate groups of allegorical figures. When rulers visited a city on the occasion of their marriage or some other joyous event, it was common for the city to stage a welcome in the form of a lavish parade of decorated carts which were floats carrying people dressed up as gods, nymphs, planets, virtues, ancient heroes, and so forth. They spent as much money on this sort of thing as Americans do on the Super Bowl.

Artists got a lot of commissions designing these “chariots” and they also made paintings and engravings depicting totally imaginary triumphal processions. Albrecht Durer did a series of them. There’s a lot of information about this in the “Joyous Festivals” chapter of Joscelyn Godwin’s The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance.