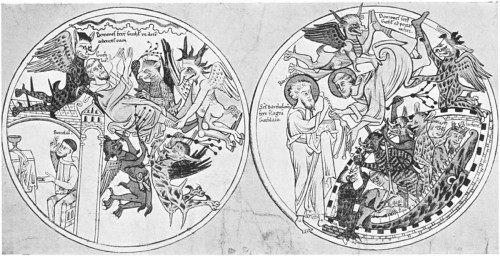

St. Guthlac and a bunch of demons.

From the 13th century Guthlac Scroll, housed in the British Library.

[Author’s Note: Before we get into the column: this summer I am looking for second-generation Pagans of all stripes for a series of profiles. Much of my material comes from thinking through my own life as someone who was raised by witches, but I’m interested in getting the stories and perspectives of other children of Pagans. The profiles will, of course, respect the wishes of anyone who chooses to remain anonymous or only known by a craft name. Interested parties should send an email to eric.o.scott@gmail.com or on my Facebook page. Now, on with the column.]

I have never known much about saints, nor have I worried about my ignorance of them. They belonged to a religion that was foreign to my own and were bound up in traditions that meant nothing to me, so I had little incentive to study them. Although I grew up in a Catholic city and had many Catholic friends, I never had reason to engage with Catholicism itself. But I do study Old English, and the way my university is set up, there would only one graduate seminar in Old English literature offered during the two years of my PhD coursework – and that seminar was about the lives of saints. In particular, the course studied a group of obscure Old English texts with no authors, simply called the anonymous saints’ lives (as opposed to the body of saints’ lives written by Ælfric, one of the best-attested authors in the literature.) It sounded painful. I signed up anyway.

My apprehensions weren’t assuaged by the class’s first readings. “Certainly Ælfric regarded himself as the apologist of the universal church,” says Michael LaPidge, an expert on these texts, “and it would have been no compliment to tell him that his hagiography imparted individual characteristics to individual saints. On the contrary, Ælfric would wish his saints to be seen merely as vessels of God’s divine design on earth, indistinguishable as such one from the other… hence it did not matter whether the saint was tall or short, fair or bald, fat or thin, blonde or brunette. In a sense it did not matter whether he was named Cletus or Clement, Narcissus or Nicasius.”

No wonder nobody wants to read these stories, I remember thinking. They’ve stripped out everything interesting for the sake of uniformity. Come to think of it, this has been my critique about everything involving monotheism.

Thankfully the texts weren’t quite as boring as I anticipated – the anonymous saints’ lives actually feature a variety of strange goings-on, perhaps because their authors did not share Ælfric’s love for universality. We read of time-traveling saints, cowardly and lazy saints, transvestite (and perhaps transgender) saints, even one saint who literally exploded out of the belly of a dragon named Rufus.

That said, although there was novelty to be found, most of the saints’ lives tended to follow a formula: the saint, born to noble pagans, rejects paganism and turns to Christianity. There the stories divide into two broad camps. In the passio genre, the saints are brought before a cruel pagan ruler, who offers them the choice to renounce their Christian faith or die; inevitably they choose to die, because that is what makes them saints. In the confessio genre, instead of martyring themselves for their faith, the saints go into solitude, denying themselves the temptations of this world. They earn their sainthood through asceticism, which is often represented as an attack by demonic forces which are repelled through their faith, in imitation of the first saint of this type, St. Anthony.

Reading literature like this is always difficult for me – it reminds me of my own otherness. The point of a saint’s life is to imagine oneself as the saint, who is in turn an emulation of God, a winding chain of models to base one’s own existence around. But I do not find connections with the saints; I know too well that they don’t belong to me. When I read these stories, I find myself thinking only of the fallen world surrounding the saint and seeing myself in that image: my face on the head of the saint’s noble-yet-damned father, my hands holding the pagan executioner’s tools. Saint’s lives are supposed to invite the reader into their moral universe, but instead, I find myself reluctantly siding with the saint’s enemies, no matter how cruelly they are described. I can’t help it. They – the fiends, the heathens – are my people.

Intellectually, I know that the “paganism” represented by Christian literature is at best a distortion of actual ancient paganism, and more often just slander – and that, in any case, the paganism of the ancient world is not the Paganism I have grown up within. I can counterfeit dispassionate analysis of these subjects in conversation and writing. But the truth is that the whole process is tremendously alienating. Perhaps this is the danger of investing so heavily in a single world to describe oneself: I can’t help but associate with the villains of these stories, even if they are vicious caricatures. They still remind me of myself.

As I write this, morning birds are singing in my back yard, which makes me think of an episode from a poem about St. Guthlac, one of Anglo-Saxon England’s home-grown saints. Guthlac, like St. Anthony, wanted to deny the world of man and goes off to live in seclusion on a hill in the wastes, so that he can better contemplate God. He is, like the other hermit-saints, assaulted by hordes of demons who hope to tempt him away from the righteous path, and failing that, to assail, torture, and distract him from his holy purpose.

Guthlac, being a saint, endures their attacks, and with the help of another saint, Bartholomew, he expels the demons from his land. Once the demons are gone, his only companions are birds, many kinds of them, who bless Guthlac with their songs. One of the poem’s final images is of Guthlac feeding the birds, perhaps anticipating St. Francis, who would preach to those same creatures some centuries later. “So that gentle spirit detached himself from the joys of mankind,” the poem says, “served the Lord, and took pleasure in the wild animals, after he had rejected this world.” Guthlac the Saint lives in a world populated by demons and songbirds; and I suspect I must be one of these things myself, but I cannot say which.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I know the feeling, in a sense. Although technically raised a Christian, of a sort, I, too, have always identified with the Pagans of antiquity. They, too, are “my people”. It didn’t help that, as a teenager in Latin class, I was reading Pliny’s Letter to Trajan in the original, nor that I recognized the *real* values of my family as ancient Pagan rather than Christian as claimed. As a Gaulish Polytheist, I specifically identify with ancient Continental Celtic Pagans, more than others. But I suspect I would have the same queasy identification that you have with the villains in the Lives of the Saints, the same doubt as to whether I am a demon or a songbird, even though my Gods stand for the good.

I wouldn’t be troubled by Horrible Pagan imagery in the Lives of the Saints. These are tales told across a sort of ethnic boundary, kind of like Palestinians and Israelis purportedly relating their sorry mutual history but each beginning and ending their narratives at different points for purposes of persuasion.

I grew up very Catholic and went, until high school, to Catholic schools. Generally, my favorite part of the schooldays was when Sister would read to us from the Lives of the Saints. Here’s one — and I do have more, just ask me — of my favorite stories: St. Theresa the Great is traveling across Spain, going from one nunnery to another. She’s riding on a donkey and there have been rainstorms in the mountains. At one point, her donkey throws her into the mud. St. Theresa looks at the sky and says to the Christian God, “If this is how you treat your friends, it’s no wonder that you have so few.” I swear that this story has influenced my relationship with divinity even long after I adopted beliefs and practices that would, beyond any doubt, have resulted in my excommunication from the Catholic church.

When I read your story, I thought, “That’s the kind of thing that Jews say to God.” And then I remembered that St. Theresa of Avila (if that’s the saint you are referring to) had some Jewish ancestry. Quite a lot, and recent, and she knew about it. Her father and her father’s father were Jews who converted to Christianity under pressure and were pursued by the Inquisition. http://www.jta.org/1981/03/24/archive/study-claims-jewish-ancestry-for-st-teresa-of-avila

I can see other qualities in St. Theresa that are more typical of Jews of both sexes than of other female Catholic saints, but this probably isn’t the forum to go into that.

Same Teresa. I can’t remember if the French Thèrese was of Lourdes or another place. Her statue is the one where she’s full of arrows and the look of eros on her face.

Love that story! I was in Catholic school only in 6th & 7th grades, and I was a righteous prig during that time.

I’ve always had a thing for Jeanne d’Arc (hey, woman with a sword!) and a fondness for St. Francis and St. Clare. Too bad the Franciscan order seldom followed his example. I think Francis did more to embody Jesus’ words and example than any other saint.

Great piece Eric !

It also reminds me of my younger school days. Where I was raised, education is hundred per cent secular but church history is very much treated like History so there’s still a good amount of propaganda left…I was raised completely non-theistically and I still remember the day, when we studied the reformation: There was a very bright picture in the History book of people destroying a church.. Unbeknownst to me at that time, the picture was supposed to represent protestants destroying the ornaments of a catholic church but when I saw the picture I immediately thought: “These guys are destroying a church, I’m with’em !”. I was, like, seven.

I took a class on Old French literature. One book we read, with an eye to translation (I think) was La Vie de St-Alexis (the life of…) When he was a teenager, he left his family with no word, and practiced asceticism and went to live under his parents’ porch! I think at 33 he did something else allegedly saintly, but I was outraged that he treated his parents so callously. I couldn’t think highly of him at all.