A view of Öskjuhlíð from the University of Iceland. The domed building is Perlan; the Heathen temple will be built on the hill’s south side. Photo by the author.

Outside of my dormitory room at the University of Iceland stretched a long and mostly empty expanse of land. Directly across the street, construction crews were erecting new campus buildings, but beyond that, I saw mostly empty ground: the pond called Vatnsmýri, the lawns surrounding the Reykjavik airport’s landing strip. In the distance there was a hill with a shining dome resting at its peak.

The dome is called Perlan, a revolving restaurant and tourist hub; the hill itself is called Öskjuhlíð. I never had reason to visit Perlan during my visit, but I came to the base of Öskjuhlíð several times –a trail leading to the beach at Nauthólsvík runs alongside it, and I often went there to swim. I got caught in a rainstorm while walking there one day, a heavy, cold rain that pierced through every piece of clothing I wore. I felt wretched. I looked up through my water-spattered eyeglasses and saw the hill before me on one side, the ocean before me on the other, and I started to laugh uncontrollably – a mystical vision from Thor himself, or perhaps just the first signs of exposure.

The site of Ásatrúarfélagið’s new temple, news of which has swiftly wended its way through the Pagan internet since Iceland Magazine published an article about it earlier this month, is only a few hundred meters away from the site of my rain-drenched epiphany. The temple, which is scheduled to be opened in autumn 2016, will be the first Heathen temple built in the Nordic countries in a millennium, and has been rightly seen as a milestone for modern Heathenry and Paganism.

The temple, or hof, has been a long time coming. “When Ásatrúarfélagið was founded in 1972, that was the first thing we said – that we wanted to build our own hof,” said the fellowship’s alsherjargoði, or high priest, Hilmar Örm Hilmarsson. Ásatrúarfélagið has been close to achieving that goal in the past; Reykjavík authorities offered the fellowship a building in the late 1980s, but the costs of renovation were too high for it to be practical.

The idea of building the temple at Öskjuhlíð has been planned since 2003, but the 2008 financial crisis in Iceland set the project back. “We lost one-third of our savings,” said Hilmar[1]. “We had been caught up in the spirit of the times, when everything seemed to be possible.”

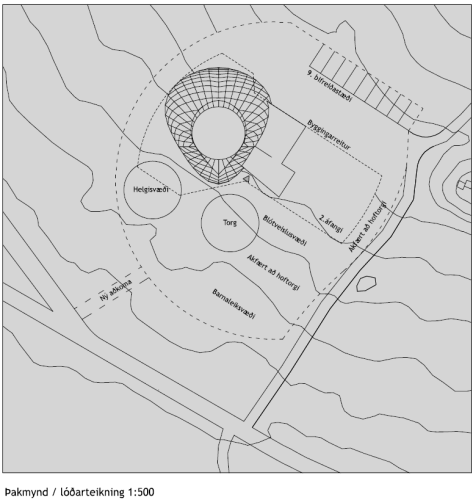

The fellowship was forced to scale back from their original ideas for the hof in order to build within their means. Part of the the solution they arrived at was to build the hof complex in two parts: the main temple, which will be opened in 2016, and a communal housing building, which will be constructed over the next ten years. This second building will eventually contain Ásatrúarfélagið’s offices, housing, and a small apartment for visiting scholars. In the interim, the fellowship’s offices will be located inside the main temple itself. There will also be a ritual area set up outside of the main building for outdoor ceremonies, although Ásatrúarfélagið has already been conducting rituals in the location for years without a specifically prepared space.

A diagram of the temple complex, including a ritual area (Blótveislusvæði), a playground (Barnaleiksvæði), and a footpath leading to the beach. [Image courtesy of Magnús Jensson.]

The new hof will also allow Ásatrúarfélagið to hold funerals in a dedicated space; Ásatrúarfélagið has a graveyard plot, which was established by a previous alsherjargoði, Jörmundur Ingi Hansen, but has not had its own location to hold funeral services. “It will, in a way, dignify it a bit more, so it’s not like a borrowed place,” said Hilmar.

The new temple has been designed by Magnús Jensson, an architect and member of Ásatrúarfélagið who has been interested in temple design for many years; one of his projects as an architecture student at Arkitektskolen Aarhus was a Heathen hof. “That hof was designed to be a microcosm,” said Magnús. “So is the new hof, but a different kind of microcosm.”

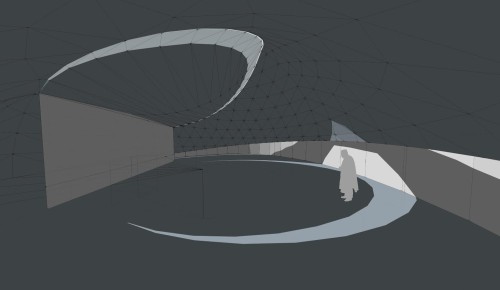

Magnús now teaches a university course that explores the relationship between architecture, sacred geometry, and religion, and his plans for the Ásatrúarfélagið hof put many of those theories into practice. His plans for the temple take into account the local landscape and attempts to build with as much on-site material as possible. The temple will bore into the hill itself, leaving an interior wall of bare rock; water will trickle down that wall and collect in streams and pools built into the floor. These features are meant to tie together the indoors and outdoors, the constructed and the natural. “The first wrong turn in architecture,” says Magnús, “was the invention of ‘indoors.'”

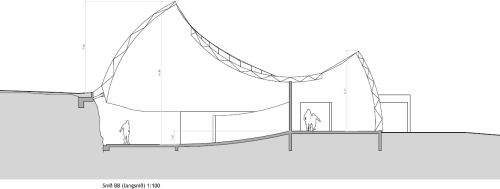

The wooden walls and ceiling will slope up into a dome. According to Magnús, the shape of the dome is meant to evoke the female form, in contrast to the phallic associations of other religious buildings in Reykjavik. Much thought has been put into the interplay of light and darkness throughout the hof; a skylight will let in shadows that change their shapes according to the position of the sun throughout the year, with different effects on the solstices and equinoxes. There are also plans for a large fireplace near the altar, as well as electric lighting, to illuminate the hof during Iceland’s long winter nights.

Inside the hof, specially-designed windows will create lighting effects that change with the seasons. [Image courtesy of Magnús Jensson.]

Magnús has hopes that his hof will bring more attention to Ásatrúarfélagið from within Iceland. “I think more people will become interested in Ásatrú when they realize it isn’t all about Vikings,” he explained. In his eyes, many Icelanders who technically registered with the state Lutheran church, but don’t really believe in it, or in anything at all; he thinks the hof may lead them to explore Ásatrú.

A cutaway diagram of the hof. Image courtesy of Magnús Jensson.

Hilmar also has high hopes for the new building. He said that Iceland’s tourist authorities have mentioned a huge increase in interest from visitors about Icelandic Paganism, and he expects that, when the hof is completed, it will become a destination for many of those tourists. “I’ve never thought about it before, to be honest,” he said. “I was getting letters of warning from friends abroad, saying we should impose a code of conduct. I was, in a way, so naive that I assumed everyone would show respect, but that’s a bit optimistic. I think we will have a great influx of people coming in, and I hope they will respect that this is our building, and it’s serving our community.”

Despite these misgivings, Hilmar believes that the hof will come to be seen as an integral part of Iceland’s national character. “Hallgrimskirkja has long since become a Reykjavik landmark,” he said, referring to the massive Lutheran state church that sits near the center of the city, the design of which is meant to evoke the basalt columns of Iceland’s landscape. “We do not want anything less for our hof. We really see it as an emblem of Reykjavik in the years to come.”

[1] As Icelandic last names are patronymic, it is customary to refer to Icelanders by their given names.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I love the design of those windows! To me, the seasonal movement of the light from the windows evokes the past without remaining stuck in it–I’m reminded of the timeless beauty of many of the Neolithic monuments of Northern Europe, while, at the same time, it’s a completely original design that probably will serve modern worshipers much better than a scholarly reproduction might.

I hope the fellowship is very pleased with its hof, and I can easily imagine it becoming a pilgrimage site for international visitors.

Certainly better than a scholarly reproduction. If the oral tradition of sacred architecture has been interrupted, the modern builder can replicate the proportions and the materials, but won’t know, for instance, why particular stones were set in particular places, or what prayers were said over trees before they were felled for timber. The old techniques for infusing spirit into the fabric of the building may not be recoverable, but human beings can develop new ones.

Great article Eric. Total thumbs up !

I had no idea that the Hof would be built by Perlan, but that’s actually quite a neat place. I can recommend the place for viewing the New year’s fireworks! Perlan also used to be the place where the Saga museum was located, a great great museum that is now by the Old harbour.

In any cases, thanks for updating us on this story !

I am stunned with the idea of having water run down the walls into pools and streams…sheers genius.

Actually I have that in my local university. It runs downs maybe 15 meters and looks awesome!

This look amazing and if I ever get the chance I will visit the site.

Terrific article, and a great companion piece to the series on pagan temples. I hope one day to visit this hof.

Pingback: Island: Neuer heidnischer Tempel wird gebaut - Asatru zum selber Denken - die Nornirs Ætt

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEXCFpiFRvw&spfreload=10 This was a proposal made for the same temple in 2008 by AUDB. Based on historical accounts of traditions, geometry and paradigm. The proposal was rejected, but there seem to be some similarities.

Mikið er ég spennt að heyra þetta! 🙂

Pingback: Ännu mera om Gudahovet i Reykjavik… | Hedniska Tankar

Pingback: “Are Humanistic Pagans building a temple in Iceland?” by John Halstead | Humanistic Paganism

Pingback: În Islanda se construiește primul templu păgân | Londra Evanghelica

Pingback: În Islanda se construiește primul templu păgân | InfoCrestin | Stiri Crestine | Resurse Crestine | Filme Crestine Online | Biserici LIVE

Pingback: A NEW temple to the Norse gods being built in Iceland | My Viking Beard