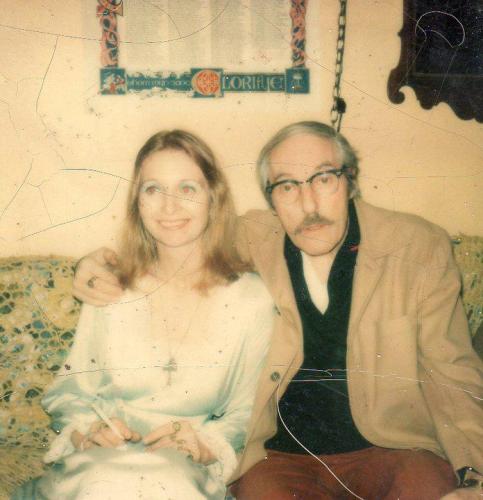

Deryk and Carrie Alldrit, the founders of the coven that would eventually become my coven – my great grandparents, in a sense.

It begins with a woman holding a candle. She is walking around the room, a guide for the priestess, who is casting the circle for Samhain. But don’t look at the priestess just yet; hear her, yes, hear the words that begin every circle in our tradition, but watch the woman with the candle. The first bit of magick walks with her – for she is not only a woman with a candle, but an Evening Star, a psychopomp, the leader on a path down into the underworld. In the double-sight of ritual, she is both physical and mythical, both our friend and an unfamiliar star. Long before we make an open invocation to a god or a spirit, the magick has already begun.

A few months ago, I had a discussion about one of my essays with my doctoral committee chair. In the essay, I talked briefly about writing rituals – the choices we make in what to include, what to leave out, and what to invent anew. My advisor was surprised and delighted by this passage, because she had never heard of such a thing: the idea of writing a ritual struck her as a novel concept. She had never thought that a religious practice could also be a creative act.

I’ve thought a lot about that conversation, because it had never struck me that religion could be anything else. Ritual writing has always been at the heart of Paganism for me, so much so that I had always assumed that was just how Paganism worked everywhere. You might keep certain touchstones from year to year – the kings of Oak and Holly, the burning of John Barleycorn, the Maypole, and so on – but the actual form of the ritual changes every time, and even those touchstones find new shades of meaning as the ritual surrounding them changes. Now I know that there are actually many Pagans who dislike the idea of “new rituals,” and prefer that the word ritual be taken more literally: a ceremony repeated year-in and year-out, a constant in the turbulence of the rest of our lives. I understand that sentiment, and even sympathize with it, but I still reject it – at least for my own purposes. For me, much of the point is to be found in adding something new that still fits into the tradition. The hard, joyful work for me is in writing a ritual for, say, Samhain, that is not the same as any Samhain ceremony my coven has ever done before, but still feels right for the occasion.

In this case, the ritual started with one image: take a dark room – a basement, somewhere literally under the earth – and turn it into the underworld. Light it with a single candle; make that candle the center of the universe. Whenever something important happens, the candle moves to that actor; when the candle moves, the circle moves with it. That idea – the candle, and the darkness surrounding it – was the first thought I had when I began thinking about a Samhain ritual a year and a half ago. Even at that remove, everything in the ritual revolved around that single point of light.

I wanted to do this in deliberate contrast to the last sabbat my friends and I had performed at last year’s Beltane. That ritual was very much about light and color. We held it outside during the day, wore bright, ostentatious costumes, and danced a Maypole covered in a spectrum of pastel ribbons. We never brought up the way we used these visual tools to reinforce the message of our ritual deliberately – there was no point at which Sarah, my friend and priestess, announced that we were wearing bright colors to subconsciously reinforce the themes of creativity and hope found in the words of the ritual. She didn’t have to; the light did that work in silence, the way the cinematography shapes a film. Our Samhain would try to do the same with darkness.

I have written elsewhere about the project Sarah, I, and the other second-generation Pagans in my family set before ourselves: a grand cycle of sabbats, one a year for eight full spins of the Wheel. I suppose I have never worked on one thing for such a long time; eight years is long enough ago that, between here and there, I’ve finished two degrees, moved to three different cities, written two books, and gotten married. To say that I’ve changed in that time is such an obvious statement as to be absurd; every cell in my body has been shed and replaced since I first drew a pentagram into salt and water at Lughnasadh. This Samhain was the final ritual in our cycle; everything else had been leading up to it.

I wanted our ritual to be thoughtful, and, if possible, kind. Samhain is, necessarily, about death. While we could have made our ceremony a hard and unflinching one – the kind where you’re reminded that death comes to everyone, that there’s no escaping it and no ameliorating it – that felt cruel to me. We have had a lot of death in our family in the past few years, and I didn’t want to hurt the grieving any more than necessary. So instead, we focused on the memory of the dead. We always walk in their footsteps, I said at one point in the ritual, but only at Samhain do the dead stand next to us in the circle. As the ritual began, I tried to visualize those members of our family who had passed on into the next world standing among us: Deryk and Carrie, Ailene, Stephen, Image, Deborah, Kelson, Tom, others whom I knew I would inevitably fail to recall. They felt closer in the darkness, in the flickering candlelight.

I don’t know what other people do at Samhain. At ours, we call the names of the dead, just before the Great Rite. It’s one of the touchstones I mentioned earlier, like the Maypole or the Holly King; it’s the moment when we give voice to our memories. I like to think of it as the holiest moment in our Wicca: the time when we remember those who have walked before us, the time when others will someday remember us. In the darkness, we call to the past. Go if you must, but stay if you will, we tell the ones who have gone before. Hail and farewell, until the next time we call their names at Samhain.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I found myself pausing, when we reached the names of your Beloved Dead, slowing down, reading them as if aloud, though inwardly… reminded of the ways we are all kin to one another, and your dead are my dead, even if we never meet, even though I never met them.

Thank you for the remembrance.

In our coven, we have present at Samhain a picture of our founding Lady, Sjanna:

http://wildhunt.org/2005/05/to-mark-passing-today-i-attended.html

This year, one of the coven, after I commented on having been mourning her longer than I knew her in life, said that she found herself mourning someone she never got to meet.

In our NROOGD coven, Dark Forest, we open up the Western Gate to our beloved dead so that they may join with us and enjoy the feast we prepare. Sometimes we have a “dumb supper”, where we eat the food brought by our coven sibs in memory of their beloved dead. After the feast, we show our dead the way back through the Western Gate, saying farewell until the next year, and close it. We also write traits etc. we want to shed, and what we want to manifest in the coming year. The fomer is burned, the latter set in water–or at least it was this year.