Casey Rae

[The following is a guest book review from Casey Rae. Casey Rae is a musician, public policy wonk and the editor/publisher of The Contrarian Media. An in-demand speaker, he gives frequent talks at conferences and campuses on issues at the intersection of creativity, technology, policy and law, and is a go-to source for major media outlets from NPR to the New York Times. Casey works alongside leaders in the music, arts and performance sectors to bolster understanding of and engagement in key policy and technology issues, and has written dozens of articles on the impact of technology on the creative community. Casey is an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and VP for Policy and Education at the Future of Music Coalition. He has served on the Board of Directors of the Media & Democracy Coalition and the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture.]

I’ve told the story more times than I can count. Five or six years old, hanging out with my high school-age uncles in a town just a couple of clicks from Stephen King‘s place and a few hurried steps through a creepy wooded path to the university where he once taught English (in the same department where my grandmother worked). Actually, “hanging out” with my uncles is probably an overstatement. More like “invading the personal space of.” The adult me is grateful either way.

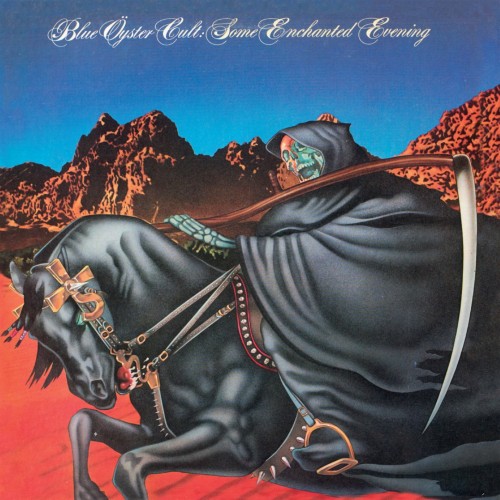

Already a monster movie fanatic on the prowl for anything scary, I would pore through my uncles’ LP collection looking for cool covers. this was the late 1970s; a golden age for outré album sleeves. On this particular afternoon, I recall pulling out a pair of records—Alive II by KISS, and Some Enchanted Evening, a concert from Blue Öyster Cult. My parents had decent taste in music, so this wasn’t so much a rock ‘n’ roll epiphany as it was an opportunity to make choices based on my own interests—in this case, horror stuff. To be honest, I wasn’t even all that curious about the music, but my uncle said we could listen.

Already a monster movie fanatic on the prowl for anything scary, I would pore through my uncles’ LP collection looking for cool covers. this was the late 1970s; a golden age for outré album sleeves. On this particular afternoon, I recall pulling out a pair of records—Alive II by KISS, and Some Enchanted Evening, a concert from Blue Öyster Cult. My parents had decent taste in music, so this wasn’t so much a rock ‘n’ roll epiphany as it was an opportunity to make choices based on my own interests—in this case, horror stuff. To be honest, I wasn’t even all that curious about the music, but my uncle said we could listen.

First up was KISS. I was definitely impressed with band members’ demonic kabuki gear and sensational makeup. The music, not so much. Even as a rock ‘n’ roll tadpole, I recognized what a shitty band KISS are. Nothing in the intervening years has changed my opinion.

Blue Öyster Cult was next. Frankly, the cover was a little too scary, depicting a black-robed skeleton astride a satanic steed, bony fingers gripping a scythe. Beast and beastie canvassed an angry Martian landscape beneath a cruel midnight sky. I had no idea what any of this was meant to symbolize, but I grokked its heaviness.

From the first needle drop I was in love. “Godzilla” was my favorite, but I was also taken by “Don’t Fear the Reaper,” which even in its live embodiment possessed a haunted quality that I couldn’t put my tiny fingers on. Still can’t.

My uncle and I subsequently had a conversation about what a “reaper” is (“he collects vegetables at harvest time”); later I went back to my own burg to ruminate over the connections between these uncanny sounds and images.

And I’ve never stopped.

I’m not alone. I can name several books by legitimate occult scholars that make some attempt to trace these ley-lines; music scribes often hint at the witchier aspects of the rock Renaissance (roughly 1964-1982). But given that each camp has limited sightlines into the other, there is an opportunity for someone to bring focus to a topic that is too often tawdry or incomplete.

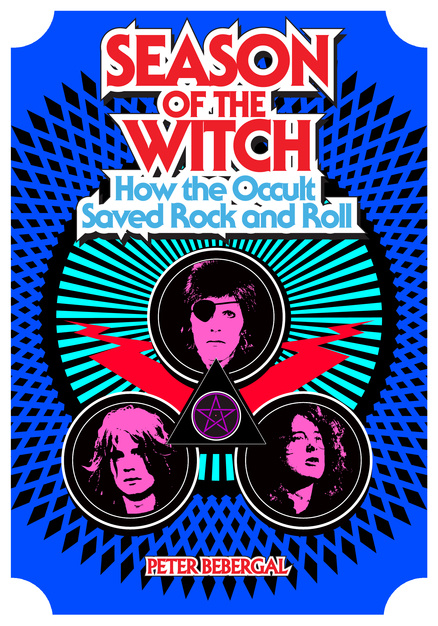

Peter Bebergal‘s Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll [Tarcher/Penguin 2014], is an admirable attempt at uniting the tribes. First, we need a common vernacular. To Bebergal’s definition, “the occult” is less a fixed system and more of a worldview that encompasses many spiritual traditions operating outside of mainstream religious practices. Bebergal’s interest in the subject appears to be fairly similar to my own—we both became enamored of rock music as a form of escapism at a time when other entertainment options were scarce or unbearably straight-laced. Rock, with its otherworldly visual language, coded lyrics, symbolic imagery and strident musicality, provided a perfect vessel for the projections of pre-adolescents and teenagers—largely male, definitely “gifted,” and lacking an outlet for our own creative impulses. We constructed elaborate mythologies around rock, populated by a pantheon of musical heroes and villains, wizards and warriors. Record albums became a kind of palimpsest, an (un)holy writ that only the initiated could hope to discern.

Peter Bebergal‘s Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll [Tarcher/Penguin 2014], is an admirable attempt at uniting the tribes. First, we need a common vernacular. To Bebergal’s definition, “the occult” is less a fixed system and more of a worldview that encompasses many spiritual traditions operating outside of mainstream religious practices. Bebergal’s interest in the subject appears to be fairly similar to my own—we both became enamored of rock music as a form of escapism at a time when other entertainment options were scarce or unbearably straight-laced. Rock, with its otherworldly visual language, coded lyrics, symbolic imagery and strident musicality, provided a perfect vessel for the projections of pre-adolescents and teenagers—largely male, definitely “gifted,” and lacking an outlet for our own creative impulses. We constructed elaborate mythologies around rock, populated by a pantheon of musical heroes and villains, wizards and warriors. Record albums became a kind of palimpsest, an (un)holy writ that only the initiated could hope to discern.

And some of us never grew out of it. Which is why it’s great to encounter a fellow traveler like Bebergal, who brings a scholar’s discipline to this esoteric quest. Bebergal is a lively writer who nonetheless resists hyperbole—quite a feat given the breathlessness this topic tends to elicit. Perhaps more impressive is the book’s comprehensiveness—from Delta blues to beatnik bluster to acid evangelists to metal overlords, Season of the Witch puts the hellfire in highbrow.

Season of the Witch is strongest in its examination of the history of African Americans as they endured the cruelties of slavery only to experience the anguish of segregation. Yet even under these injustices, black Americans preserved elements of their original musical and spiritual traditions, some of which were channeled through Christianity. It is difficult and often ill-advised for those outside a specific cultural group to construct a narrative around the real struggles of a people. Especially when the topic of investigation has been used by the socioeconomic and political elite to perpetuate harmful stereotypes. To his credit, Bebergal avoids many common pitfalls. His comparative analysis of early rock ‘n’ roll and its cultural and spiritual foundries compels examination of the African-American experience. To sidestep these histories is to ignore America’s own troubled past and potential for a better future. Key to the latter is for today’s generations to become more familiar with America’s musical and cultural legacy, including its abuses.

Those who enjoy cultural anthropology and religious studies will find plenty to appreciate in Bebergal’s account of how West African trickster god and “guardian of pathways” Eshu connects to Papa Legba, the guardian of the spirit world in Hatian (and later Louisianan) Voudon. When confronted with the all-pervasive Christian dichotomy of good/evil, these spirits took on a more sinister shape, one that to Bebergal’s reckoning informs the devilish stereotypes found in Delta blues, and later, rock.

But this is hardly a singular ethnomusicology. For his next trick, Bebergal pegs Greco and European mythologies (Dionysus; Pan) to the pagan urges present in 1960s American and European counterculture. This flowering—which ultimately inspired the civil rights agenda along with the LSD-soaked technolibertarians of Silicon Valley—paved the way for a fuller exploration of the occult by progressive rockers of the 1970s, some of whom made a serious study of such metaphysical thinkers as Paramahansa Yogananda and G. I. Gurdjieff, among others. Acting as an accelerant was The Beatles, whose fraternization with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi served as a cosmic permission slip for legions of seekers.

It’s clear that Bebergal has done real investigation; the ideas of such occult luminaries as Madame Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley are given more serious consideration than is common to your average rock tome. For example, Bebergal does not refer to Crowley as a “satanist”— an inaccuracy common to pretty much every book on Led Zeppelin I’ve ever read (and I’ve read them all). And even occult scholars make mistakes; a recent book on Crowley noted that the Zeppelin LP on which “Do What Thou Wilt” was inscribed was IV, not III. This may not seem like a big deal to the average reader, but if I can’t trust you to get a detail like that right, can I trust you to illuminate how Rosicrucianism came to Europe?

While it is clear that Bebergal has done his homework, he hasn’t fully soaked in the hermetic traditions of the West (aka magick and its many offshoots). That’s not necessarily a bad thing. There are other writers, such as Erik Davis, who hit that groove. Bebergal is forthright about how he has less of an interest in the occult as a standalone topic than exploring how the symbols and associations found in rock got there to begin with. To me, this makes his occult research that much more impressive. I’ll take Bebergal’s even-keeled examinations over dilettantism or pedantry any day.

My only real complaint with Season of the Witch—besides jealousy over having not written it—is that its informational organization is a bit awkward. Not much of a gripe, given the difficulties in synthesizing and systemizing such a broad range of concepts and histories. Bebergal’s presentation is like a particularly awesome grad school lecture—it occasionally meanders, it’s not entirely concise, but is rich in context and conviction. (Apparently, we also share a lecture style.)

Some may grouse about what the book leaves out, but let’s give Bebergal a break—it would be fundamentally impossible to catalog every tributary that connects such massive bodies of water. That said, it would be interesting to teach a class in rock and the occult in a manner that could capture even more correspondences. If I were to design such a course, I’d readily assign Season of the Witch as the introductory text.

Kudos to Bebergal for taming the wily spirits of rock long enough to capture their essence in this fascinating book.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I just wanted to say “thanks” for the great review and bringing this book to my attention. Most of the books out there which mention rock and the occult do so poorly. Out of the Zeppelin books, I thought Mick Wall’s “When Giants Walked the Earth” treated Page’s obsession with Crowley reasonably well. At least Wall didn’t fall into the “Crowley is a Satanist” trap.

Again, thanks, there’s a small group of us in Pagandom who are really interested in these studies. I hope you write more here at the Wild Hunt!

More Cowbell!

Nice article. I saw BOC back in the day, and Black Sabbath with Ozzy sometime in the 70’s. I was in a fundamentalist situation at the time, and those people really believed that bands like this were channeling Satan. Made it even more fun. At the BS show someone in the row I was sitting in was passing along a bong filled with orange soda….Thanks for the memories!

Great review….I’ve ordered the book and will look forward to reading it! For those interested, you might want to check out Alan Richardson’s book “Earth God Rising” (1995) It’s got a great description of experiencing the God at a Rolling Stones concert!

Some good sources for reading about African American sources in Rock and Roll: “Hear That Long Snake Moan” by Michael Ventura (from his book of essays called _Shadow Dancing in the USA_ (1985). The “Long Snake Moan” essay is available on the Internet.

Also, on the same subject, Julio Finn’s book _The Bluesman: The Musical Heritage of Black Men and Women in the Americas.”

Oh, and I recently found an interesting article on David Bowie’s spiritual proclivities (expressed in his music and lyrics) called “The Laughing Gnostic” by Peter R. Koenig.