Two weeks ago, at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio Valley, California, director Hiro Murai premiered a shortened version 0f “Guava Island,” a collaboration with Donald Glover (Childish Gambino), who stars in the film with the singer Rihanna. Murai was also the director of “This is America,” a music video which echoed loudly throughout this production. The film’s score was composed by Michael Uzowuru, an American record producer, and the songs were performed by Glover as Childish Gambino, using many similar moves from “This is America.” They were accompanied by an Afro-Cuban cast of actors, dancers and musicians.

The plot of the film opens as an animated folk tale about the creation of the world. Quickly we learn that island is the center of the world and upon it “the seven gods of the seven lands created the dueling truths: love and war.” The film then continues as an elaboration of the binary and dueling elements in the fictional island. Even the main characters, introduced first as animated children, display the pull-and-push tension of their relationship.

Guava Island [Amazon Studios.]

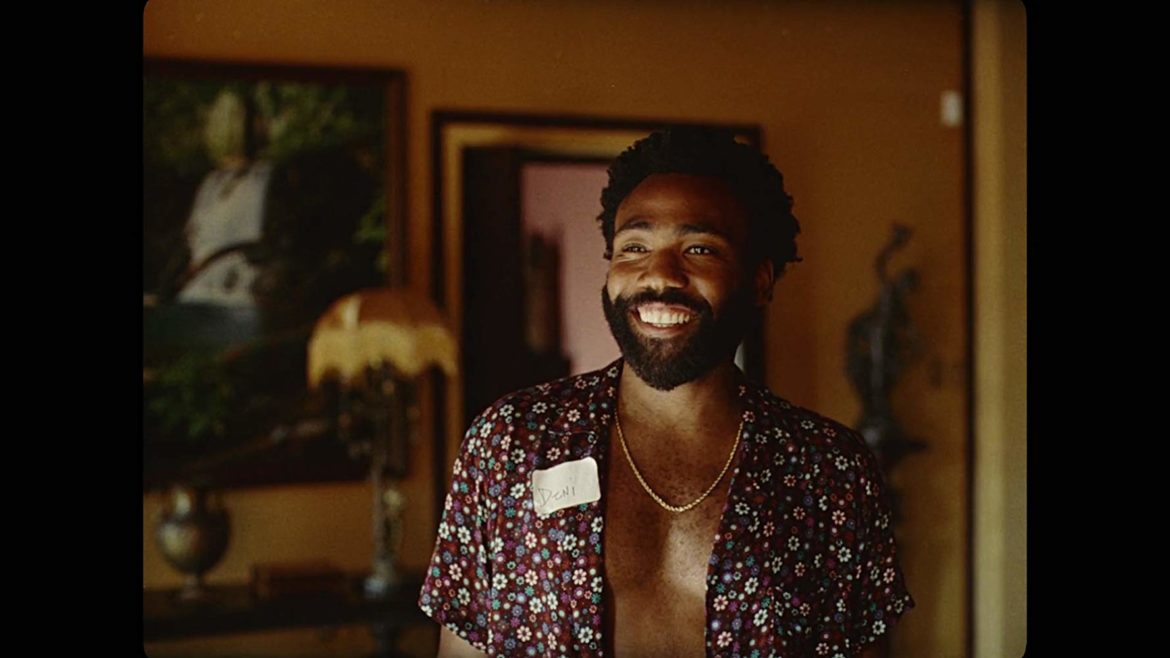

Glover plays Deni Maroon, a Cuban musician planning to throw a musical festival on the island so that the residents, who are forced to labor seven days a week, can have a day off. Deni’s girlfriend and muse, Kofi Novia (Rihanna), seems always concerned about Deni’s plans, if not his whole approach to life. She is tempered and cautious while he is carefree. Their relationship centers the film, and by doing so, makes the story a romantic comedy about the dangers of capitalism and the power of a patriarchal totalitarian state.

The villain – or perhaps the manifestation of the villain – is Red Cargo (played by Nonso Anozie, who will be familiar to Game of Thrones fans as Xaro Xhoan Daxos.) Red is the powerful island boss who runs the main business of the island, the export of a perfect blue silk. Through Red, we learn of the basic conflict in the film: Deni’s festival conflicts with Red’s business. As Deni awakens to injustice, Red’s attention focuses on the threat that awakening poses.

The film juxtaposes the cold and seemingly difficult work life of the residents against the backdrop of paradise, a tropical island that is lush and productive. Deni poignantly comments about their lives: “We live in paradise, but none of us has the time or the means to actually live here.”

Donald Glover as Deni in Guava Island [Amazon Studios]

The relationship to Glover’s “This is America” is obvious, with similar themes of oppression, violence, distrust, and systemic racism added to new themes of colonialism and economic imperialism. “Guava Island” is just as captivating and poignant as its progenitor video.

“Guava Island” was filmed in Cuba as a secret project, but it was not much of a secret. The imagery and music instantly give the location away, at least to those familiar with Cuba. But there is more to it than the location. The codes of Afro-Cuban spirituality are more than merely woven into the film; they glow.

When the Orisha came to Cuba, they touched everything. Anything touched by Cuba will carry their energy, their ashé. And “Guava Island” glows with ashé.

The casual but constant presence of the spirits is embedded throughout. We see hints in the early part of the film, and then, we are immersed in its spiritual elements. A woman randomly blesses a picnic prepared by Kofi. We do not witness all of it, but after he asks Kofi’s permission, she blesses each item on the picnic blanket, even the napkins, making a request of them: “Que limpien la locura del diablo” (“May they clean the devil’s madness.”)

Perhaps most obvious signs of the Orisha are the Afro-Cuban rhythms that permeate the film. From street dances to performances, the beats echo wemileres, the sacred drumming used to summon and honor orishas. The musical performances seem to follow oru, the word used to describe the musical liturgies of the Lucumí people. Even the instruments themselves are familiar, and in some cases, are part of sacred invocations.

Kofi portrayed by Rihanna [Amazon Studios.]

The colors within the film are another sign of the spirits. They aren’t just any red or blue or yellow. They are crimson, cerulean, and gold, the colors of Chango and Yemaya and Oshun – the rulers of this story about power and war, motherhood and protection, and love and sensuality. There are even traditional pairings of colors like red and blue and red and black. They echo the story of the divine twins, the Ibeji, and their dance that overcame Eleggua, the trickster and gatekeeper orisha.

Finally, what struck me most about the film and its association to Afro-Cuban spirituality is the presence of iwá, the essence and irrepressible elements of the human character. Deni, Kofi, and Red are all driven by their nature. They are fulfilling who they are. The music and the colors surrounding them are backdrops for their iwá. Their essences are stronger than forces against them. They are not in a façade of free will but rather an expression of their authentic selves and intention.

The film is as layered with Afro-Cuban spirituality just as it is layered with socio-political and economic commentary. It also stays constant to its story of dueling truths: knowingly, Deni describes the setting of “Guava Island” by saying “this is America.” The story works as a fable, a commentary, and a treatise about work and freedom. But most importantly, at least to my Cuban eyes, it holds the radiance of orisha.

“Guava Island” is now available on Amazon Prime Video.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.