Last Friday, January 16, was National Religious Freedom Day. You may have missed it. There has been a lot to keep track of lately: icy conditions, oily shipping lanes, polar boundaries, the occasional yelling at allies, and even re-gifting prizes.

While some local media outlets briefly noted interfaith observances and educational events, the most visible coverage came from conservative media sources. These outlets largely framed the day as an affirmation of religion-forward policies associated with the Trump administration, emphasizing faith-based initiatives while sidestepping the nation’s constitutional foundation in the separation of church and state and the broader principle of universal religious liberty.

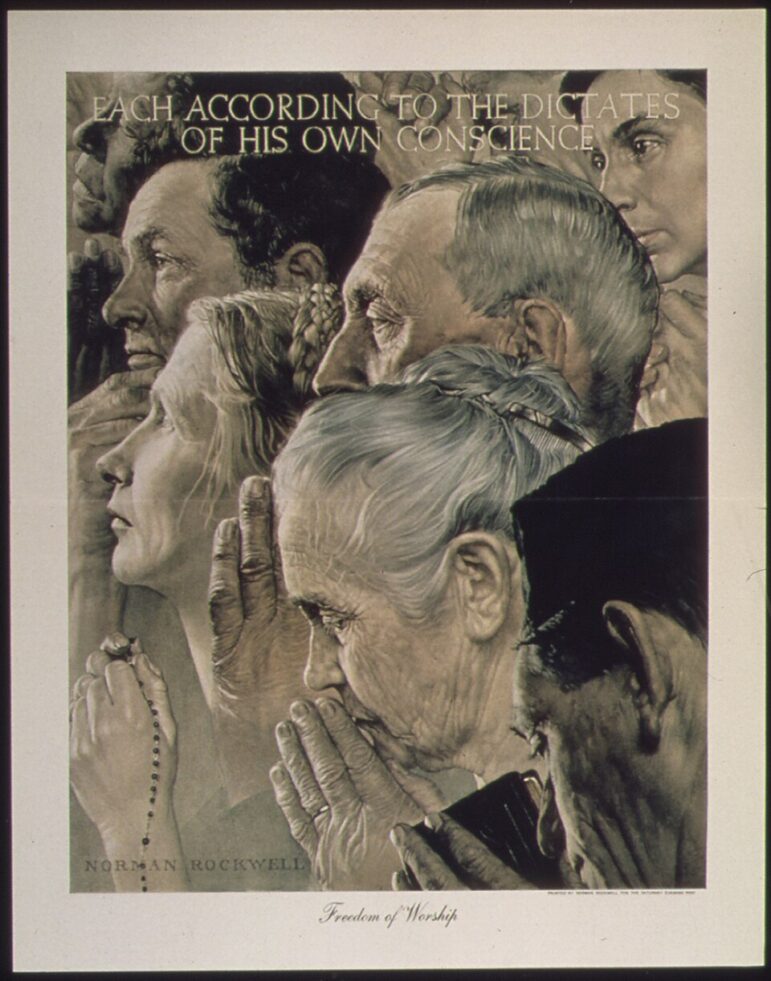

Norman Rockwell, “Freedom of Worship,” from the Four Freedoms series [public domain]

For context, Religious Freedom Day commemorates the adoption of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom on January 16, 1786. The statute stands as one of the most consequential documents in American legal history, laying the philosophical and legal groundwork for the First Amendment. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson in 1777 and championed through the Virginia General Assembly by James Madison nearly a decade later, the law represented a radical break from centuries of state-sponsored religion.

Jefferson regarded the statute as one of his three greatest achievements, alongside authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding the University of Virginia. It was so significant that he requested it be listed on his tombstone. The statute declared that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship” and that civil rights must not depend on religious belief. In doing so, it dismantled the state’s financial support for the Anglican Church and established, for the first time anywhere in the world, a legal framework protecting freedom of conscience as a civil right.

The Virginia Statute directly inspired the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, embedding the idea that government must remain neutral in matters of religion; not hostile to faith, but prohibited from endorsing, funding, or enforcing it. Religious liberty, as envisioned by Jefferson and Madison, was a shield: a protection for belief, disbelief, and diversity alike.

Since 1993, U.S. presidents have generally issued annual proclamations marking January 16 as Religious Freedom Day. Although it is not a federal holiday, the day has served as a symbolic reminder of the nation’s commitment to pluralism, tolerance, and the protection of conscience. Across administrations, proclamations have emphasized dialogue, minority protections, and the importance of allowing Americans to practice any faith, or no faith at all, without government interference.

Recent presidents have used the day to address contemporary challenges. President Biden’s proclamations highlighted a “shocking rise” in antisemitism and Islamophobia, framing religious freedom as inseparable from democratic values and community trust. In earlier years, he emphasized rebuilding confidence among minority faith groups and reinforcing civil protections.

President Obama consistently framed religious liberty as a universal human right, not merely an American one. His proclamations underscored pluralism and global religious persecution, explicitly affirming that the First Amendment protects the right to practice “any faith at all—or no faith at all.” He drew attention to violence against Coptic Christians in Egypt, Rohingya Muslims in Burma, and Baha’is in Iran, while stressing that religious liberty requires a neutral state, not a confessional one.

President George W. Bush focused on faith-based charities and conscience protections while repeatedly reaffirming that the United States “gives to bigotry no sanction.” In the years following September 11, his proclamations emphasized tolerance and unity among churches, synagogues, temples, and mosques alike.

President Clinton, who signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, was the first to offer proclamations following a joint congressional resolution, and used Religious Freedom Day to warn against government overreach and to draw attention to hate crimes and church arsons, particularly those targeting Black congregations in the 1990s.

Even when invoking religious language, these presidents largely maintained a consistent framing: religious freedom as a constitutional protection for individuals, not a mandate for religious expression by the state.

The 2026 proclamation issued by President Trump on Friday marks a significant departure from that tradition.

While earlier proclamations, even those by President Trump in his first administration, essentially treated religious freedom as a safeguard for private conscience and public diversity, the 2026 text reimagines it as a tool for cultural and political renewal. The language shifts from protection to promotion — from neutrality to advocacy. Where prior presidents framed government as an impartial guarantor of liberty, the current proclamation positions the executive branch as an active leader in a “resurgence of faith.”

“For 250 years,” the proclamation states, “our Nation and our people have abided by a simple truth: Every person is born with the God-given right to practice their faith.” It goes on to describe the United States as “the only Republic ever founded upon this sacred principle” and calls for a renewed commitment as “one glorious Nation under God.”

The shift becomes more pronounced as the proclamation explicitly rejects faith as a private matter. It declares that the administration is “boldly bringing faith back to the public square” and links a “revolution of common sense” to “a resurgence of faith in God.” The language moves beyond commemoration into prescription, urging religious expression within schools, the military, hospitals, workplaces, and the “halls of Government.”

Unlike previous proclamations, which invited reflection or encouraged interfaith engagement, the 2026 text calls on families to gather at places of worship to “praise Almighty God” as a national act. Religious expression is framed not as a personal choice, but as a civic virtue.

Equally notable is what the proclamation elevates as its central concern. Rather than emphasizing security grants for all houses of worship or protections for vulnerable religious minorities, the 2026 declaration introduces a “Task Force to Eradicate Anti-Christian Bias.” This marks a departure from decades of language that avoided privileging any single tradition. While prior presidents spoke broadly of protecting religious minorities, this proclamation explicitly prioritizes one faith for executive action.

The historical framing also shifts. While continuing to ground religious freedom in the Virginia Statute, the Enlightenment-era arguments for conscience are dimmed, and the proclamation then leans heavily on the Mayflower narrative and the concept of “God-given rights.” The legal architecture of religious liberty, its roots in restraint of government power, receives far less attention than religiously infused narratives of national identity.

Taken together, the 2026 proclamation represents a fundamental redefinition of Religious Freedom Day. What began as a commemoration of legal restraint and pluralism is recast as a call for religious assertiveness and state-facilitated faith expression. The long-standing metaphor of religious freedom as a shield is replaced by something closer to a sword—an instrument for shaping public life according to a particular religious vision.

This shift raises the stakes for religious minorities, particularly those whose beliefs or practices are frequently framed, explicitly or implicitly, as non-Christian or “anti-Christian.” The scope of that designation remains undefined. It can encompass traditions that venerate horned deities, theological positions emphasizing personal responsibility for salvation, or even routine boundary-setting requests that proselytizing cease in shared civic or workplace spaces. In this context, “anti-Christian bias” is broadly invoked while evidence of systemic persecution of Christians in the United States remains thin, yet repeatedly asserted, leaving minority communities such as ours vulnerable to subjective enforcement and uneven protection.

As the nation marks 250 years since the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the contrast is striking. Jefferson’s statute sought to protect belief by limiting government. The current proclamation seeks to renew belief by activating the federal government. Whether that shift honors or undermines the legacy of religious freedom remains an open and, frankly, deeply consequential question.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.