TORONTO, Ont – On March 30, the news was announced that 37-year old Murali Muthyalu was being charged with fraud over $5,000, extortion and “pretending to practice witchcraft.” This last charge is an unusual occurrence in Canada and invokes Section 365 of the Canadian Criminal Code, which refers specifically to the false practise of witchcraft and other occult or “crafty science.”

Muthyalu, who also goes by the name “Master Raghav,” is a citizen of India that has been a visitor to the country for less than a year. He was advertising his services as an astrologer and psychic in the Toronto area throughout February and March.

![[Pixabay]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/tarot-991041_1280-500x333.jpg)

[Pixabay]

Section 365 of the Criminal Code also made news on March 8, when Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould announced at a press conference that she was going to introduce legislation to overhaul the criminal code, eliminate so-called “zombie laws” and other antiquated regulations that are still on the books.

The name zombie law refers to sections of the Criminal Code, which have been overturned in case law often because they have been deemed unconstitutional by a judge. An example of this is the law against “procuring miscarriage” (abortion).

Section 365 on the practise of witchcraft specifically does not qualify as a zombie law, because it has never been overturned. However, it is one of those being recommended to be included in the list of laws to be removed. Other dated and obscure charges on the list include, dueling, water-skiing at night, and making and selling crime comics.

The Canadian Criminal Code was codified in 1892, and has been updated on an as-needed basis. The original section regarding witchcraft is a holdover from the old witchcraft laws that were on the books at the time in England, which is from where Canadian law was adopted. The Code had a major overhaul in the 1950s, and a review in the 1970s.

The specific section regarding witchcraft has raised concerns in Canada’s Pagan, Witchcraft and Wiccan communities before this point. While charges under Section 365 are rare, the wording of the law raises some interesting discussions. It is included under Section IX: Offences Against Rights of Property, in Section 361 – False Pretences, which states:

361 (1) A false pretence is a representation of a matter of fact either present or past, made by words or otherwise, that is known by the person who makes it to be false and that is made with a fraudulent intent to induce the person to whom it is made to act on it.

The law was created as protection from fraud, including incidents where gullible people are taken advantage of by unethical fortune-tellers, who “pretend” to have information or skills, and will give this to the victim in exchange for money.

The exact wording of the law has changed very little since 1892. The only significant difference is the addition of the word “fraudulently”, which was added in 1955. In its entirety, the code reads

Section 365 – Pretending to practise witchcraft, etc.

Every one who fraudulently

- (a) pretends to exercise or to use any kind of witchcraft, sorcery, enchantment or conjuration,

- (b) undertakes, for a consideration, to tell fortunes, or

- (c) pretends from his skill in or knowledge of an occult or crafty science to discover where or in what manner anything that is supposed to have been stolen or lost may be found,

is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Kerr Cuhulain, a retired Vancouver Police officer, prominent pagan author, hate crimes investigator and anti-defamation expert, spoke to The Wild Hunt, and explained the significance of the wording included in Section 365.

“This law has to do with pretending to provide a service for money,” Cuhulain explained. “The word ‘witchcraft’ in this law doesn’t refer to religion, it refers to magic. The courts really can’t interpret this as a religious law because then they’re crossing into human rights laws, that protect people’s rights to choose their spiritual path.”

Typically it is people who advertise themselves as mediums, clairvoyants, or psychics, and charge their clients large sums of money for their services, that are the ones who get charged under Section 365 as well as under more serious charges of fraud.

For each fraud case, the sentence is up to 14 years. A charge of witchcraft can result in a summary conviction, which amounts to six months in jail and/or a fine of $5,000. During the plea-bargaining process, the witchcraft charge is usually dropped, and the accused is convicted only under the fraud charges.

In April of 2014 a man named Yacouba Fofana, who worked under the name Professor Alfoseny was arrested for fraud and also charged under Section 365. In his advertising, he made the claim, “Great clairvoyant medium, solves your problems, return of the beloved, luck, gambling, protection, etc. Guaranteed results.”

He was found to have taken one of his victims for $5,000 CDN.

In 2012, Gustavo Valencia Gomez was arrested in Toronto for defrauding a 56-year old woman’s family for $14,000, claiming that her physical ailments were the result of a curse, and that using a series of spells and rituals, he could lift it. The charges were dropped when he agreed to pay restitution to his victims. However, he was charged again when more victims came forward.

In 2009, there was another headline-grabbing case in Toronto. An experienced criminal lawyer, Noel Daley, was defrauded by a woman claiming to come from a long line of witches, and that she could read tarot cards. Vishwantee Persaud pleaded guilty to four counts of fraud in this case, and the charge of witchcraft was withdrawn as part of her plea deal.

Persaud also claimed to be possessed by the spirit of Daley’s dead sister, and bilked him out of at least $27,000 CDN.

Given that fraud law has been effective in convicting individuals who do take advantage of desperate people, does Canada require the 125-year old witchcraft law to remain on the books?

Cuhulain has a straightforward answer: “I don’t think that there is. If you take money from someone, and don’t deliver services, that’s a civil offence. If you misrepresent yourself and your abilities to take money from someone, that’s a fraud.”

So – is it illegal to be a Witch in Canada? The answer is no, it is not illegal to be a Witch, Pagan or practitioner of any other spiritual path. The Toronto-based criminal law firm of Kostman & Pyzer spell it out quite clearly on their website, stating:

It is a crime to practice witchcraft in Canada with the intent to deceive another by pretending to exercise or to use any kind of witchcraft, sorcery, enchantment or conjuration.

In order to be found guilty of witchcraft, the Crown Attorney must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused person engaged in fraudulent activity while pretending to practice or use any kind of witchcraft.

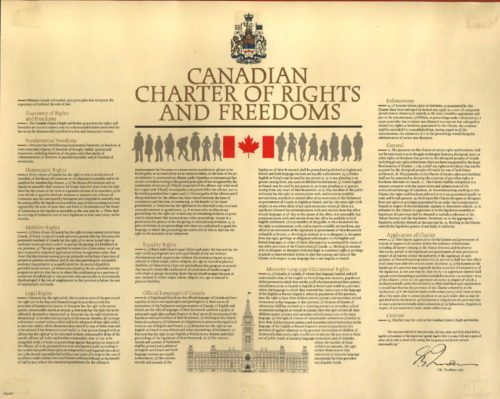

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms promises all Canadians freedom of religion and belief. This trumps any conflict that could arise from the Criminal Code. The proposed overhaul announced on March 8 should bring the two documents into accord.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

For Pagans and Witches concerned about Section 365, a quick read of Section 2 – Fundamental Freedoms, in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms should help clarify the situation:

Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

(a) freedom of conscience and religion;

(b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

(c) freedom of peaceful assembly; and

(d) freedom of association.

There is no date set yet for the removal of Section 365, or Pretending to Practice Witchcraft, from Canadian law. As this is not a zombie law and has not been deemed unconstitutional in court, it falls into the second category of outdated or irrelevant regulations, and remains open to debate and discussion. The Wild Hunt will update this story as it progresses.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

I quite agree with Kerr Cuhulain that Section 365 is redundant to more rational laws covering fraud. Subsection (a) is also insulting; substitute any denomination with churches and see how they’d feel about it. It is also hidden dynamite in that it could be abused by unscrupulous prosecution to harass Witches for being Witches even if a conviction were implausible. Subsection (b) has a dangerous built-in ambiguity; how can one tell if a given act of fortune-telling is fraudulent or just wrong?There’s an interesting quirk in subsection (c) if you go back to the original intent of the authors, ie, before “fraudulently” was inserted: (a) and (b) did indeed ban witchcraft and commercial fortunetelling outright. But (c) already had the word “pretends” in it, suggesting that at one time Canadian legislators believed it possible to authentically find misplaced or hidden things by occult means and, more to the point, that doing so was not a social offense as witchcraft and commercial fortunetelling were perceived to be.

Strictly speaking, any Catholic priest who undertakes an exorcism or even the consecration of communion hosts should end up in the hoosegow for subsection A.

It’s odd that all the examples mentioned in the article are people who are identified as non-Canadians or whose names don’t sound white. I’m guessing that it’s a bias in how the law is applied, rather than introduced by the author. Can anybody with more knowledge clarify?

Precisely, the names are not Anglo-Saxon. It is indeed a red flag. Possibly they are adding a 365 specification for people not liked by someone in the prosecution chain, and dropping it to force a plea bargain. Another good reason to ditch 365.