There is something special about being a polytheist. Belief and practice with multiple gods necessitates an understanding that all gods are real. Certainly, polytheists argue over a “hard” or “soft” approach, debating whether the gods are actual individual entities or exist in a more archetypal manner, but either way a polytheist is able to accept another person’s religious experience with another deity as valid. We are comfortable with experiences that differ from our own. This is much more difficult in monotheistic faiths.

But what about when a polytheist is confronted with the miraculous claims of a monotheist? Can two seemingly opposing cosmologies live together? Can one overcome skepticism of the “other” religion while still validating their own cosmology?

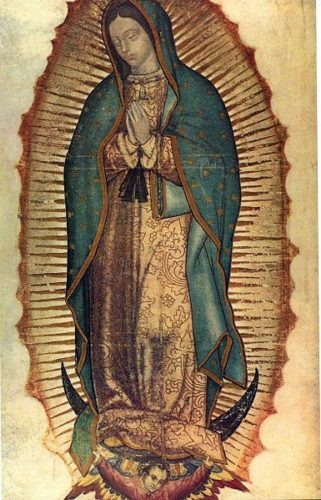

This was the question in my mind as I entered an exhibit at the Bower Museum’s new exhibit. Entitled “The Virgin of Guadalupe: Images in Colonial Mexico,” the installation documents the origins of the Virgin of Guadalupe, an apparition revered by Mexican Catholics as symbol of religious favor and national pride, yet often derided as a hoax meant to convert and oppress the native, pagan population.

Photo credit: Tim Titus

As told in the exhibit, the story of the Virgin of Guadalupe enfolds though the experience of an illiterate, converted Aztec man named Juan Diego. While Diego was out walking on the hill of Tepeyac on the morning of December 9, 1531, he was called to a spot on the hill. There, a unique manifestation of the Virgin Mary appeared to him in all her glory and spoke to him, giving him a message for the local Catholic bishop. Diego tried to take the miraculous message to Bishop Zumárraga, the highest religious authority of the colonial government, but he was sent away.

The virgin appeared to Diego three more times, however, and finally instructed him to gather special roses into his tilma (cloak) and carry them to the Zumárraga. He did so, and when he unfurled his tilma to reveal the flowers to the bishop, the famous image of the Virgin of Guadalupe shone out, imprinted forever on Diego’s tilma. A church in honor of the virgin was constructed at the manifestation site. The original image, emblazoned on a poor peasant’s cloak, became a source of religious worship, Mexican pride, and large-scale conversion of the native population by its colonizers. Her feast day is December 12.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The image on the tilma, and now on countless canvases, candles, and items of jewelry, contains icons that brilliantly combine the competing Catholic and native Aztec spiritualities, including symbols that many modern Pagans would recognize today. A young, dark-skinned woman in a pose of prayer stands or kneels in the center, rays of light streaming out from her body. She wears a 12-pointed crown and a cloak covered in stars, and stands on a crescent moon held by a youthful angel. The icon combines power with reverence, but it gives that power to a woman. The entire shape is quite clearly yonic in nature.

Catholic and native symbols combine seamlessly. The Virgin Mary is easily suggested, and her pose is one of Catholic prayer. She is held by an cherub and in a pose of submission, and her unbound hair is a sign of maidenhood. Yet the ribbon around her waist was an Aztec signifier of pregnancy. The flowers inscribed on her lower half, particularly a four-petaled one on the lower right, hold native meaning. The crescent moon would appeal to the locals, but the fact that it is held up by an angel suggests the dominance of the invading culture. Her cloak of stars could likely be seen through either culture’s eyes: is she descending from the heavens above or is she Queen of the Earth covered by the sky? The exhibit relates the star patterns on her cloak to the constellations of the zodiac. Is her 12-pointed crown significant of the zodiac signs, or of the apostles?

Many within the Pagan and Polytheist communities have had direct contact with spirits or deities. It is a relatively noncontroversial belief that entities can and do present themselves through visions into the physical world. Since polytheists admit the existence of multiple gods, it is intellectually honest to admit that the Hebrew god may have communicated and manifested himself through Diego and this image. If Zeus can speak to you in meditation, why can’t another god speak to a young Aztec? Therefore, those who practice a polytheistic faith must accept the possibility that the virgin is a true message from a deity.

[Photo Credit: Tim Titus]

![The Christian god "creates" The Virgin of Guadalupe [Source: Wikimedia Commons]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/VOG_God-365x500.jpg)

The Christian god “creates” the Virgin of Guadalupe [Source: Wikimedia Commons]

Brian Dunning at skeptoid.com points out the other side of these arguments. He notes that Bishop Zumárraga, to whom the miraculous image was first revealed, never wrote a word about it. It seems strange, to say the least, that a Catholic bishop who wrote prolifically during his career would never say a word about a miracle that manifested before his own eyes. Dunning also notes that the major recounting of the story comes from a text written after both Diego and Zumárraga had died. How did the writer hear about the story?

Dunning adds to his argument the fact that the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, who conquered the Aztecs, was from a region of Spain known to worship an image of the Virgin Mary with dark skin, and that he carried a statue of her with him to Mexico. The natives, he argues, would identify with the dark-skinned statue. Plus, Cortés knew a monk who was both an accomplished painter and familiar with Aztec language and customs.

A representation of the conquering faith that incorporated symbolism of the subjugated, Cortés would have reasoned, would be a powerful weapon in subduing the locals, and it was. There is no question that the conquered citizens of what is now Mexico were successfully converted to the faith of the invaders. In fact, Latin America is now one of most staunchly Catholic corners of the world.

But, as magicians know, one must be careful with the energy they send out. The Virgin of Guadalupe also figures prominently in the expulsion of Spain from Mexican lands. The Mexican revolution against Spain began on Sept. 16, 1810 as Miguel Hidalgo invoked the Virgin of Guadalupe as a symbol of Mexican patriotism and pride in his famous “scream” for independence:

Will you free yourselves? Will you recover the lands stolen three hundred years ago from your forefathers by the hated Spaniards? We must act at once…. Will you defend your religion and your rights as true patriots? Long live Our Lady of Guadalupe! Death to bad government! Death to the gachupines!

While the “miracle” led to the spiritual takeover of the native Mexican population, it also led to the Spain’s loss of its conquered lands and the return of freedom to the people of Mexico. The new energy of independence placed into the image on a humble peasant’s cloak forever changed a country’s future. That is magic in action.

Is the Virgin of Guadalupe a piece of magic or a deliberate hoax meant to subvert a colonized population? The answer may lie at the crossroads of these two questions. Magic is performed in the in-between spaces: crossroads, circles, mountaintops. It manifests in strange ways, and it is sometimes said to return to its creator in ways he or she cannot predict. Is it at least possible that this image of the divine feminine was placed by deity for its own purposes, beginning at the hands of a conqueror but finally turning against its creators and ending in the hands of a free people who constantly strive to overcome lingering effects of colonization? Whatever one’s belief, it is undeniable that this image of the divine feminine has powerfully constructed and reconstructed an entire corner of the globe. She may indeed have become, as the exhibit ad banners name her, “the most powerful woman in the world.”

* * *

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

As a Brazilian-American pagan who continues a long family tradition of Mary worship, I can assure you the power of all Marys is very real. This article grossly oversimplifies the issue of the role of Mary in postcolonial Mexico. For starters, the answer to your question is “both.” La Virgen is an entity deeply shaped by colonial forces who has been used by the colonizer to try and subdue indigenous practice, but she has also obviously been there to help her people. Additionally, you didn’t contextualize La Virgen with other global instances of Mary worship in postcolonial nations. You didn’t contextualize her to saint worship, nor to the syncretic practices of colonized people. This article comes off as a request for research funding, but doesn’t give any concrete reason why you specifically should be doing the research.

P.S. If you read Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldua she reveals one secret of La Virgen, who is a VERY specific entity that is a bit separate from other Mary’s. Don’t blink or you’ll miss it.

The concept of “Mary” is one of the many pre-xtian aspects of paganism the Catholics appropriated during the spread of the religion throughout Europe. The importance of a Mary in Mexico probably speaks more to an appeal to a prextian Aztec deity than the appearance of a European or Palestinian figure to indigenous people in the process of being enslaved by an occupying force. How better to reduce conflict than to encourage religious conversion? Especially if that new religion stresses the “fact” that humans are fallen creatures and should expect to suffer in this life in the name of salvation? Yahweh is a trickster figure and a war god. The concept of “Satan” is nothing more than an aspect of Yahweh. Deception is a method his priests use to advance his cult. Mexico is no different from the rest of the world in that respect.