“What if,” I say idly, “I started celebrating Christmas again, but in an Arthurian sort of way?”

“Camelot is the Christian wart on the face of pagan England,” my husband grumps. “Look at it. Its got roots all the way back in Wales, but every year there’s another layer shellacked on top. When people talk about the Arthurian myths, they’re talking about stories that come up well after Christianity.” He pulls a disgusted face and folds up to rest his arms on his knees, and his chin on his arms so that he can glare like a proper gargoyle. “There’s nothing pagan about the ‘cup of Christ’. People talking about the grail quest like it’s anything but a doomed, Romantic version of the Crusades. The best we get is a story or two about spirits and spellworkers that might be English locals – but the hero of the story is the King. You know what the monarchy has done for England?”

I grin, charmed by his dudgeon as I always am. “Probably more of an idea than I have any right to,” I admit.

He snorts. “Anglophile,” he mutters, and unfurls enough to pull me in fondly. “The whole point of Arthur, these days, is that he unites England under one flag. That is colonialism at its core. It’s a myth of empire, and the righteousness and justice of a Christian empire, at that. Any other reading of it-”

“Like Bradley,” I offer, just to watch him grimace.

“Like Bradley,” he says. “Which I know you haven’t read. She’s going directly counter to nearly a thousand years of mythology. She’s making up something new – just like Gardner did – out of a bunch of loose parts.” He tilts his head at me, annoyed, but when I grin at him he does grin back. “What?”

“I just think it’s a fun thing to read at Christmas,” I say, and he makes a terrible noise. “No, I mean it. Like – what do you think about Susan Cooper’s stuff? I don’t think you can argue that the Dark is Rising series is Christian.”

“I’m not saying all of the books are Christian,” he mutters. “Y’all have been reading against the text and making it work for ages. I am saying they’re not Arthurian.” I give him a doubtful look and he meets it, stubborn. “They deal with the idea of Arthur, sure. And in that, they’re still arms of imperialism, but-”

King Arthur as one of the Nine Worthies, detail from the “Christian Heroes Tapestry” in The Cloisters, New York. Dated c. 1385.

“Now hang on,” I interrupt. “They’re written by a woman who’s left England for America. I would argue they’re more Welsh than English. Even Cornwall gets more screentime – I don’t think you can say Cooper’s arguing for the British empire.”

“She’d best not, she’s writing too late,” he says with a smirk. “No – but she’s invested in the binary. There are good people, and there are bad people, and the good people are old and wise and should be running the show. Normal humans can accomplish stuff, but it’s this higher level of person that is really in charge and we should all trust them? What is that except an argument for aristocracy?”

I scoff. “A book written for children? I think it’s okay to have kids hear that there are people who are older than them who have more power than they do and are on their side. That’s a reflection of reality, for kids! Besides, it’s not like she portrays the Old Ones as unproblematic or entirely trustworthy. I’d argue that it’s the kids and the ‘lower class’ that are the heroes of Cooper’s books.”

“My point,” he says, shifting back to when he was winning the argument, “is that they deal with the idea of Arthur but they don’t engage with the mythology, really. It’s why they’re so hard to pin down. She really does try to cut out all of the growth of the myth and get back to the roots. It’s why the books are so disinterested with Christianity. Go back that far and it’s just another religion trying to make sense of things, not the force that choked off English spirituality.”

“That’s one hell of a claim,” I say, flat, and he grins at me without the first sign of repentance.

“Fine – that took over the dominant narrative. Better?” He gestures, magnanimous. “But even Cooper focuses in pretty tight on Christmas.”

“Cooper’s explicitly talking about the Yuletide,” I say. “Do not make me get Hutton out – you know better than I do how weird the Yule traditions get.”

“Weird doesn’t mean pagan,” he says, stubborn. “Just because you don’t remember the origins of something doesn’t mean it predates Christianity. People forget how weird Christian traditions get – especially once they’ve had a minute to stew in their juices.”

“I just think you’re guilty of focusing on the origins as much as any of the folks trying to read against Christianity in the myths,” I say. If there’s a little frustration in my voice, well, that’s part of the fun. “Whether we like it or not, modern Pagans are stuck with Christmastide. It’s so embedded in Western culture folks don’t even notice it, most of the time. Trying to find ways to engage with it that feed our spirituality isn’t practicing Christianity – it’s finding ways to be Pagans and having lives and families in a specific modern culture.” I wave a hand. “So if I… want to sing the Wren Song and the Dilly Carol, I don’t think it matters if those were originally Christian, or if Christians sang them, or-”

He waves a hand to cut me off, and I idly consider biting it. “What I’m saying is that this idea you have of linking Christmas with Arthuriana as your way of celebrating it is Christian,” he says. “I’m not talking about anyone else.”

“Well what am I going to do?” I ask. “Celebrate Yule? Tried that.” I shrug, uncomfortable still in my failure. “The sun is going to come up whether or not I sit vigil for it – and all I get out of the deal is a sleepless night and a stomach ache. This is what I’m talking about.” I gesture emphatically. “Our niece is five. She wants to celebrate Christmas. Her grandparents want to celebrate Christmas. I want to celebrate with them. I need something to help me make sense of that, so that I am not just defaulting to Christianity.”

He gives me a look that holds more skepticism than anything he could say.

I roll my neck and consider. “Listen. The Arthurian myths make a big deal of Christmas, but they’re mostly not concerned with the birth of Christ. It’s about having feasts and seeing miracles and wonders on the day. It’s an opportunity for adventures.”

He nods. “In which they subdue the wild magic of the land, yes, go on.”

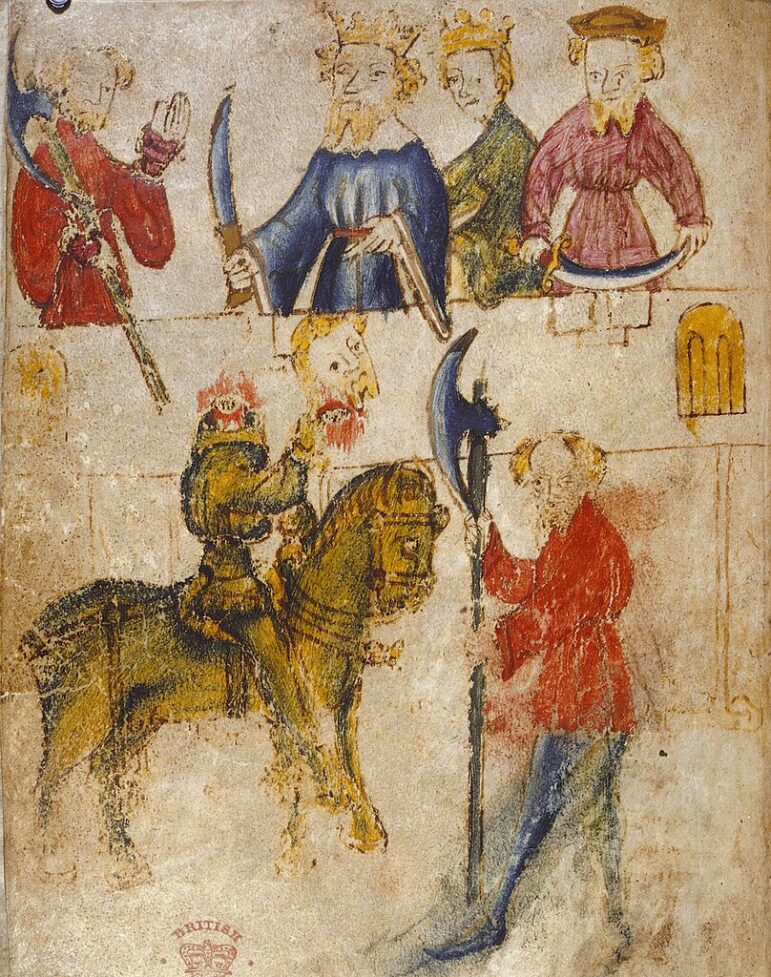

Illustration from the manuscript of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, c. 14th century.

I bristle, and charge ahead. “That’s a framework I can steal. I like the idea of Christmastide as a time of adventure, set aside from the rest of the year as especially holy, a light in the dark of winter. I like the idea of it as a time where I might see glimpses of the magic of the land. I can use that.”

He sighs. “That happens because Arthur, the king of the land, demands those wonders. Are you the king of the land? Does it serve as an extension of your body? Do you have divine right to-”

“We’re back to imperialism,” I mutter, and he slaps my thigh, grips it, uses it to shake me gently but emphatically.

“We are back to imperialism,” he agrees. “You cannot engage with the myth of divine kingship without getting back to imperialism. Talk about an idea that’s too ingrained in Western culture. Kingship, aristocracy, they’re both inherently based in the idea that some people are better and therefore everybody else should listen to what they say. That’s the underlying paradigm that’s really ruining western society, and I am not going to be party to it.”

This time it’s my turn to scoff, and he gives me a dirty look. “You get two kinds of kings in the myths,” he says. “One tells you what to do and is right and just. The other dies and is a sacrifice. Arthur manages to be both, and they are both, inherently, Christian.”

“Hot off the presses,” I say, sarcastically. “All divine kings are Christian. Someone tell Freyr.”

“We are not getting into the mess of interpretation and cultural projection that makes Freyr a king,” he says. “That’s not my point. My point is that the myths are clear that Arthur is a king because of battle and divine right. He is an inherently English king, and the English monarchy has used his myth for centuries to illustrate how they are chosen by their god to subdue other peoples and bring them into a holy empire. They were very successful at it. You may have heard.”

“That doesn’t mean I’m condoning the British Empire,” I sigh. “It’s just – sometimes it’s nice to think that there’s someone who is good, and just, and has a right to lead. It would be nice to be able to follow someone like that. I get it.”

King Aurthur from Epitome of Chronicles, first half of 13th century

“Yes,” he says, and grips my hand. “It would be nice. It would be a huge relief. And that is the kind of thinking that leads nowhere good.” He sighs. “Some people have more power. We have to constantly remind them that is because we have all agreed to give it to them. We have to hold them to higher standards around it. Or – maybe they shouldn’t have it. Maybe nobody should have that kind of power.”

I pause, and then, grin a little. “If nobody has that kind of power, then maybe I can demand portents and miracles for myself. After all-”

He laughs, and cuffs me gently, and drags me close. “You’re no king. I do not recognize your authority.”

I jostle against him. “Just as well that Twelfth Night’s passed, then.”

He makes a terrible noise. “You mean Epiphany, the baptism of Christ?” he groans, and I laugh.

“I mean the one where you give me jumping aristocracy,” I say. “Hand over your tribute, sirrah.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.