Editor’s note: There’s a brief mention of mythological sexual violence.

Apple season is coming to a close up here in the Northern Hemisphere, and with November rapidly approaching, it’s time to direct your attention to Pomona, the Roman mistress of the orchards.

One of the older Roman gods without a Greek counterpart, referred to as numens, or spirits, Pomona was later considered a nymph or a hamadryad – Greek terms that referred to lesser goddesses of trees and natural places. Uncountable in number, very few nymphs are ever mentioned by name and even fewer were worshiped in their own right. Pomona, however, was something of an exception, because unlike her sisters she wasn’t just a goddess of trees or wild places but specifically their domestic cultivation. Pomona was a goddess of farmers and farming, taking on an important role in an agrarian society dependent on her work, and her benevolence, for their survival.

Pomona, Goddess of the Fruits, from the Goddesses of the Greeks and Romans series (N188) issued by Wm. S. Kimball & Co. [public domain]

The legend goes that Pomona, who cared for all fruiting trees, not just the apples that bear her name, shunned marriage despite her beauty. (Though why that’s always a “despite,” why beauty should equal a desire for marriage, is another matter.) Many gods desired her for a wife, but she enclosed herself in her orchard, grafting, pruning, and imposing fruitful order on the chaos of the wild.

Eventually the shapeshifting Vertumnus, god of seasonal change, plant growth, and gardens, convinced her to marry him by appearing naked in front of her, selling her on the concept of marriage through lust alone. It helped that he was the most perfect specimen of male beauty anyone could imagine. It helped that she had been alone all this time, with pent up energies that needed somewhere to go. That somewhere ended up being her vines and trees, their passionate, active marriage providing bountiful fruit for their mortal followers to eat.

Of course, this being a Roman myth, Vertumnus’ actual intentions on throwing off his clothes after yet another rejection were violent rather than persuasive. Pomona’s unexpectedly positive response all the steered the narrative towards its happier ending, if unknowingly falling into bed with your would-be rapist can be called happy.

There’s a lot to examine and analyze there, from both cultural and spiritual perspectives. We can look at what it tells us about the natural forces at play, how this interaction reflects the natural world, the knife edge line between benevolence and violence, cruelty and abundance. We can also draw out the human from the divine, see Roman cultural norms imposed on these far from human figures, and what that tells us about who the Romans were, to each other and themselves. It’s beyond the scope of this article to fully explore the Roman attitude towards sex and violence and gendered power dynamics on display here, but I hope one of you writes about it.

Apples on a tree [Pixabay]

It’s a popular belief, even among some academics, that Pomona had not just one but two festivals dedicated to her in the Roman state calendar: the first on 13th August, when summer’s bounty is in full swing, and the second on 1st November, when the final harvest is done and her work for the year is finished. Unfortunately, this doesn’t seem to have been the case, with an 18th century (or perhaps even earlier) mistranslation that duplicated her husband’s midsummer festival at the end of October, and an assumption that one or even part of both festivals must have been dedicated to her worship, responsible for the error.

Compounding this confusion is the coincidence of apples, introduced to Britain by the Romans and spreading westward from there, and the prominent role they play in British and Irish Halloween traditions. For those convinced of the historicity of Pomona’s festival it’s a reasonable supposition that the apple magics and food traditions were drawn from there, and historians often include this imagined festival when discussing the pre-Christian influences on the development of Christian Halloween. In reality, the starring role of apples during Halloween is likely down to their ubiquity at this time of year – food based magic most often draws on what’s available to the practitioner, landing on staple foods and seasonal abundance. The stuff of life, and the stuff you’re most likely to have in your pantry.

In truth, it’s most likely that Pomona had no festival at all, as the sources we have detailing the Roman state religion are thorough, and make no mention of one. However, this does not mean we can’t celebrate her, and on the days mistakenly assigned to that purpose no less. As authors like Morgan Daimler and Mhara Starling have taken pains to point out, “modern” doesn’t mean “wrong” or “meaningless” when it comes to religious practices; the problem comes when we assign them false historical roots and a tradition that isn’t there. Not because older forms of worship are inherently superior to newer ones, but because the truth and authenticity matter. Knowingly clinging to a lie just because it makes for a better, prettier narrative makes mockery of what we’re doing. The gods deserve more respect than that, and so do you.

What you do to celebrate the mistress of the orchards, should you choose to do so at all, is entirely up to you. I myself am personally unlikely to, but that’s because I have enough gods and spirits already of my own. Pomona is not a being who’s sung out to me – my own practice tends to be rooted in place, or close by, and Italy is rather far from Scotland. Still, as someone who studied Greece and Rome at university – and before that a proud graduate of the mythology-obsessed child to queer adult pipeline – I’m happy to bring her to the attention of those who might benefit from knowing her, and to suggest a festive dish that is as likely please the our modern palettes as the Ancient Romans who first developed it.

Whatever you do on November 1st, I hope you enjoy yourself, and eat some delicious food.

Apicius’ Minutal of Fruit

“In a sauce pan put oil, broth and wine, finely cut shallots, diced cooked pork shoulder. When this is cooked, crush pepper, cumin, dry mint, dill, moisten with honey, broth, raisin wine, and a little vinegar, some of the gravy of the above morsels, add fruits the seeds of which have been taken out, let boil, when thoroughly cooked, skim, bind, sprinkle with pepper and serve.”

-Apicius 3, 16, translated by Joseph Dommers Vehling

As you may have gathered, Roman recipes are a little different than what we’re used to. The contemporary cookbook, where everything is carefully timed and measured, is actually a relatively modern invention. Prior to the 19th century, when people started bringing a more scientific approach to the kitchen, recipe books were something of a choose your own adventure scenario, and it was up to the individual cook, with their skills and expertise, to turn the often vague instructions into something recognisable and delicious.

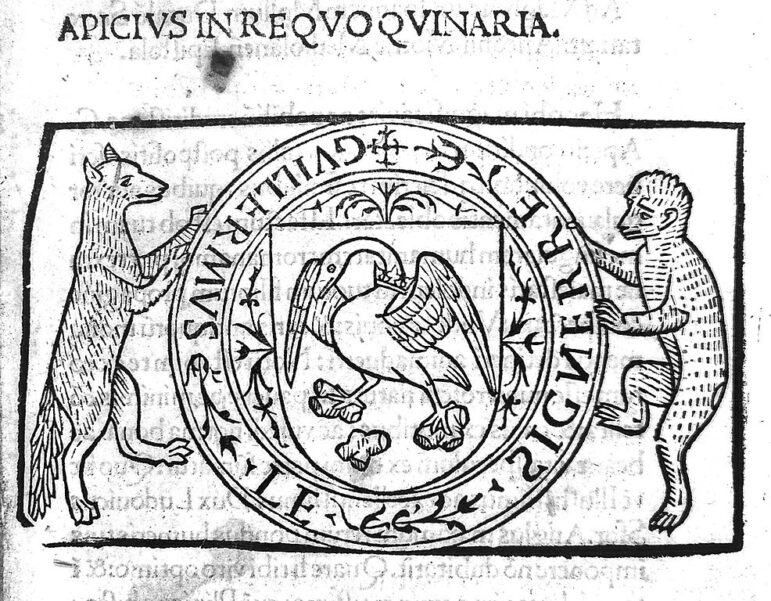

Apicius, title page to an edition of De re coquinaria, 1498 [Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

Apicius was the Roman gourmand, his recipe book the primary source for historians trying to reconstruct Roman gastronomy. This wasn’t the everyday fare of your average peasant (we can better learn that from sites like Pompeii); this was haute cuisine, the food of senators, high ranking priests, and wealthy equites, Rome’s aspirational middle class, people who were limited only by sumptuary laws and seasonal imports when it came to food.

Many of Apicius’ recipes will likely seem strange or deeply off putting to the modern reader. The inclusion of brains and other less popular organs, the pairing of fish sauce and fruit, and the use of meats like flamingo, dormouse, and hare, are largely alien to us in the West now, but that doesn’t mean they should stay that way – or at least, not all of them. While the fish sauce and fruit combination is, according to several food historians, absolutely delicious, and organ meats, including brains, are having something of a culinary revival right now, quite a few of Apicius’s ingredients are extinct, poisonous, or endangered. Experiment, have fun, but use common sense and always research what you’re using before you put it in your mouth or bring it into your kitchen.

I’ve chosen Apicius’ Minutal of Fruit for this column because it provides a nice, easy gateway to reconstructed Roman cooking, offering us a more familiar flavour profile than some of his other fruit and meat dishes. In some ways it reminds me of a Moroccan tagine, especially if you interpret the original Latin praecoqua as apricots rather than ripe fruit – the non-specific “fruit” element of the recipe given to us by Mr. Vehling. Similarly, though Vehling translated it as “broth”, the actual Latin word used by Apicius in that part of the recipe is liquamen, a type of fish sauce, which would provide a different flavour profile entirely. Unfortunately Vehling’s work is not the most accurate, but English translations of Apicius are few and far between (and my own Latin is terrible) so make do we must.

Those brave enough to have already attempted reconstructing this recipe recommend using Nam Pla or another, similar brand, of East Asian fish sauce as a substitute for liquamen (as well as for garum, if you move on to recipes involving that more famous Roman fish sauce). This information, in addition to the advice to use matza crackers or matza meal as a thickening agent (the “bind” part of the recipe), is all the help you’re going to get from me in reconstructing this dish – because I’m not going to tell you how to cook it.

Pause for a moment of outrage.

I know, I know. This is a food column, recipe writing is my job, what on earth do I think I’m doing? Half the fun of this sort of thing is figuring it out for yourself, the way our ancestors, if they were lucky enough to be able to read, have access to a cookbook, and the right ingredients to make whatever was in it, would have. This also allows you to customize it to your tastes in a way that I think better reflects how people would have approached the process at the time, treating recipes more like suggestions than commands.

The Wild Hunt would really love to see your version of the dish, what fruit you use, which mint and peppercorns make it into your seasoning mix, how you balance the savoury, sour, and sweet flavours at play. There are so many options here and I’m excited to see what you make of it.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.