CHICAGO, Ill. — Chicago Pagan Pride coordinator Twila York and Rev. Angie Buchanan, founder of Earth Traditions and Gaia’s Womb, were recently invited into a local public high school classroom to share a bit about their religious practice and beliefs.* The teacher contacted York through the Greater Chicago Pagan Pride website, and after a brief email conversation, she was asked to present to a world religions class. York enlisted Buchanan’s assistance, and together they offered two forty-minute sessions on Paganism.

![[Public Domain]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/640px-Latin_Public_School-500x375.jpg)

[Public Domain]

Because Buchanan had more experience with presenting to teens, she began each class and York followed. Each of the sessions included an an explanation of the Wheel of the Year, seasonal cycles and “how we all are part of the earth because we breathe in life and when we breathe out we die.” They brought various altar tools, including “a Tarot deck, wooden candle holders, Pentacle plaque, song bowl, crystals, Sage bundle and a pestle and mortar.”

York recalled, “The students and the teachers were open and very curious about what we had to say. They wanted to ask questions and felt comfortable doing so […] What was wonderful about their questions is that they were thought out and were not the usual “are you devil worshipers […] Some of the questions they asked were: ‘Do we have a religious text like a Bible?’ ‘What activities do Pagans do on Samhain?’ ‘What do Pagans think about other religions?’ ‘What are thoughts about the extinction of the dinosaurs?’ We even had a student ask about shamanism.”

Several days after the sessions were over, Buchanan and York received letters from the students thanking them for taking the time to share their religious beliefs. Both women reported that they have not received any backlash personally; nor have they heard of any backlash or complaints aimed at the teacher or the school. York said, “[The teacher] has asked Angie and I if we would be interested in coming to speak to her classes about Paganism every semester. We are so excited that this opportunity was offered and that we have another invitation to go back.”

While this particular teaching moment went well, that is not always the case. Teaching religious literacy in public schools can be a very sticky issue. It is dependent on the school’s location, the city’s religious climate, the support of the administration and the teacher’s own ability to navigate a difficult subject in a public forum with minors. That is not easily done.

In 2013, another Illinois high school teacher, Greg Hoener, invited a local Wiccan, Lydia Gittings, to present Paganism to his classes. It didn’t go over as well as York and Buchanan’s experience. At the time, Gittings told The Wild Hunt: “There were a couple of students who were visibly uncomfortable in each class […] but I remained positive and kept going back to science. I wasn’t there to convert.”

In 2013, another Illinois high school teacher, Greg Hoener, invited a local Wiccan, Lydia Gittings, to present Paganism to his classes. It didn’t go over as well as York and Buchanan’s experience. At the time, Gittings told The Wild Hunt: “There were a couple of students who were visibly uncomfortable in each class […] but I remained positive and kept going back to science. I wasn’t there to convert.”

But the problems continued weeks beyond the class itself. Eventually the principal and the school board began to receive parental complaints. In a letter to the editor of a local paper, one angry mother wrote, “Since parents were not notified in advance, I had no opportunity to express my deep concerns in this matter and to prevent my son and his classmates from being exposed to potentially dangerous information about the occult.”

But problems do not only arise when Paganism and other lesser known minority religions enter the classroom. In a recent story out of Virginia, a high school geography teacher asked “students to try their hand at writing the shahada, an Islamic declaration of faith, in Arabic calligraphy.” As reported in the Washington Post, the Augusta County Public School System was immediately inundated with complaints, which eventually began streaming in from all over the country. These complaints turned violent, forcing the administration to close the school down for several days. In a statement, administrators said, “We regret having to take this action, but we are doing so based on the recommendations of law enforcement and the Augusta County School Board out of an abundance of caution.”

The geography teacher was accused of indoctrinating students. While some supported the teacher’s assignment, others, with tempered reactions, simply felt it was inappropriate. However, in this case, the more extreme reactions were attributed to Islamaphobia.

Virginia educational standards do allow for religious literacy education, as do many state systems. Other recent reports from schools around the country describe teachers asking students to recite the Muslim statement of faith aloud, to write their name in Sanskrit or in Hebrew, to try on head scarves, to read the Ten Commandments and the Five Pillars of Islam. One high school reports taking a yearly trip to a local mosque. Not all of these cases caused an uprising, but some did. Teaching religious literacy is a very slippery slope, and there is a fine line between the teaching about world religions, and the teaching of religion.

![[Public Domain]](https://wildhunt.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Bhs_int_classroom_ss-500x377.jpg)

[Public Domain]

AP Human Geography is a college-level high school class that focuses on learning geography through human culture and society. Staruch said, “We study the geography of religions specifically so we are most concerned with where each major faith originated, where it has spread to, and the explanation of how it got there. Furthermore, we look at the different ways in which each religion impacts the landscape where they live (e.g. what structures do they build, what do they do with the deceased, do they make pilgrimages to specific holy sites). Finally, we deal with the potential problems that occur and/or have occurred in territories where multiple religious groups occupy the same space (e.g. Orthodox Christians and Sunni Muslims in Serbia).”

Looking at the curriculum, the classes can also cover, to some degree, the world’s minority religions within that geographical framework, including Paganism.

Echoing what York and Buchanan saw in their recent teaching experience, Staruch said, “The students are great with the material. They are usually pretty interested and ask great questions. The beautiful part about teaching [at this school] is that most of the religions we study are represented in the hallways.The kids want to know about their peers’ beliefs and they want to know more about why certain groups behave the way they do.” And he believes that this education is vital to the children’s growth and to their futures.

He said, “Religion is something in which many people believe very strongly and devote significant amounts of time to practicing. Unfortunately, people spend very little time trying to understand other people’s religious beliefs. […] It is essential for those of us in education to deal with these misconceptions and misunderstandings fully and in a way that promotes tolerance for minority points of view and a more nuanced, enlightened perspective on the differences that exist but that don’t necessarily need to divide us.”

This belief was echoed by Reverand Hansen Wendlandt of the Nederland Community Presbyterian Church (NCPC), who began a religious literacy learning program in his local Colorado community. Like Staruch, he believes that religious literacy is vital to a child’s future and noted that “There are fewer and fewer opportunities for kids to learn about different religions – to become religiously literate.” He wants to fill that gap with is private program. As we reported, Rev. Wendlandt welcomed two local Wiccan priestesses in October. The women offered an overview of Paganism including a hands-on project, and it was well received. Since that point, the program has attracted the attention of many local residents as well as a public world religions high school teacher, all of whom have been supportive and encouraging.

However, there are differences in teaching religion in public schools and in a private setting, church or otherwise. Public schools are government-run and bound by the same laws as any other government space or agency. Therefore, public school teachers must be extremely careful in their negotiating of religion education. Did the assignment to copy Arabic writing cross a line because the students were asked to write a religious text? Or is the teaching of the writing itself a problem? Is the trying on of a head scarf or looking at Witchcraft tools cultural education or a form of indoctrination? What about the field trip to a church or mosque? And, how do you share theology? Does simply hearing the words of a religious prayer pose a problem?

The answers to these questions will vary from person to person; from family to family; from community to community. That is where it becomes sticky.

When asked if there were any specific teaching rules and regulations that might help instructors avoid pitfalls or help administrators guard against problematic employees, Staruch said no, adding, “My teachers know to stick to information that is a part of the curriculum in order to prevent the line-crossing issue.”

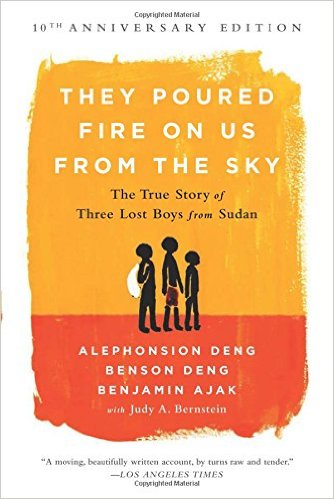

He said in all ten years of teaching, he has experienced only two problems. In one case, the children were asked to use an online “which religion are you” calculator. When it didn’t predict one girl’s religion, she got upset, and the parent complained. Staruch said, “I apologized, explained the purpose of the assignment, and it didn’t go any further than that.” More recently, a Muslim parent was concerned that the summer reading book, They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky, “painted Muslims in a negative light.” In an email response, Staruch explained how the book is used to teach about religious belief and religious extremism in that region of the world. He added, “She appreciated my email and I never heard another word from the parent the rest of the year.”

He said in all ten years of teaching, he has experienced only two problems. In one case, the children were asked to use an online “which religion are you” calculator. When it didn’t predict one girl’s religion, she got upset, and the parent complained. Staruch said, “I apologized, explained the purpose of the assignment, and it didn’t go any further than that.” More recently, a Muslim parent was concerned that the summer reading book, They Poured Fire on Us from the Sky, “painted Muslims in a negative light.” In an email response, Staruch explained how the book is used to teach about religious belief and religious extremism in that region of the world. He added, “She appreciated my email and I never heard another word from the parent the rest of the year.”

Staruch is passionate about his work and the subject matter, and he has managed to walk the line carefully in his field. He also teaches in a area that is religiously diverse and, because of that, his experiences are mostly positive, as was the case for York and Buchanan. Other areas of the country are not as open, as is evident by numerous news report and stories.

Regardless of the situation, navigating the teaching of religious literacy in public schools can be a figurative minefield. Rev. Angie Buchanan offered this advice for anyone asked to be guest in a classroom: “I would agree to a presentation for informational purposes only. I would not agree to a ritual. Keep your explanations very general. Advise the group that you are sharing your personal beliefs and practices, and not speaking about the particular practices of others; that this is a very diverse group of people; that we do not speak for all Pagans. Be prepared to ask leading questions when you see that there is hesitancy on the part of the students to ask. Animal sacrifice came up, as did questions about witchcraft. However, both had to be prompted. […] I would advise maintaining a basic sense of boundaries and ethics with regard to disclosure of identity when dealing with minors and school systems.”

* Names were omitted to protect the identity of the students and other teachers involved.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.

Teachers should exercise great caution about encouraging students to recite or copy out prayers or other sacred words of religions that the teacher has only a superficial knowledge of. The same goes for leading students in any religious practice.

Reciting aloud the Muslim declaration of faith that begins “La ilaha Allah . . .” is regarded by some Muslims as a statement that you either are a Muslim, or wish to convert to Islam. Anyone who does so and then recants is subject to penalties for apostasy.

Knowing that in Judaism, any paper or parchment on which the Hebrew name of God has been written is supposed to be kept forever in a safe place and never discarded, I would never ask students to copy out any Islamic religious text in calligraphy. That’s either incredibly ignorant or deliberately disrespectful. Throwing away the practice materials might be viewed by Muslims as an act of sacrilege comparable to burning a Koran.

Many religions, including the indigenous ones, have restrictions or taboos on the their ritual or religious materials. A teacher from a different background can’t be expected to know those rules and is likely to break them out of ignorance or carelessness.

I don’t often use the phrase “secular humanism” as an insult, but this kind of casual treatment of other cultures’ holy things seems to stem from an assumption that nothing is sacred. If the teacher has an agenda of promoting his or her own religion in a public school, something that Protestants have been known to do, that is also unacceptable.

When I was starting out, most of the groups I knew of deliberately would not instruct anyone under the age of consent.

I agree that people should learn what they can of other faiths and paths. I don’t think religion belongs in the public schools. Public schools are compulsory, students can’t walk away if they do not agree. I bet that most readers here would not approve if it were Christianity we were reading about.

I don’t think there should be public schools, but that is a completely different topic.

Faith is a personal choice, it shouldn’t be encouraged by a school district or any public arm of the state.

I would not mind if Christianity were taught in a non-Christian location, or a flavor of Christianity that is rare in the locale in question. Teaching the class their own flavor of Christianity is redundant and adds to the privilege of the already privileged. I would object to a public school class being led in the Lord’s Prayer; that crosses the line into indoctrination, though I’ve no problem presenting it as a text. Generally I harbor a skepticism along the same lines as Angie Buchanan and Deborah Bender express.Here in Ohio the Legislature has made things worse by passing a redundant law “protecting” religious expression in classroom, exams, etc; again privileging the already privileged. Some other state has tabled a law that permits use of the Bible in teaching a whole raft of topics including biology and geology. I can understand why this stuff drives the New Atheists into a frenzy.

I don’t agree, but your point is well reasoned.

Why not let the schools offer such classes as being optional? I know I was in HS before all the “No Child Left Behind” crap, but we had classes that were optional (as in outside the purely scholastic sphere) like choral, sports, and theater. Make it a comparative religions, philosophy, or just plain humanities course. Explain it to parents but don’t make it a rule that they must sign papers for their children to participate because I know I’d have forged a signature to do so before I’d have let my parental-units know I was interested in such.

First, let me say again that I think public schools are a mistake.

With that said, your idea has possibilities. There would be issues, such as the school staff deciding what is and is not a real religion. And someone should make sure that there were at least three Christian choices. There’s an old saying about two churches would fight but thirty would coexist.

Finally, there is a question of a religion forcing it’s morality or other codes on others. To me, this is the most important question. Just as one example, I don’t think women should be forced to cover their bodies and faces.

I’m a big believer that “your beliefs shouldn’t govern my behavior.”

Your idea might work if everyone walked a very fine line. And yes, the parental consent is absolutely necessary.

The only safe way is no religion in the public schools-period. No teaching about, no dealing with it at all. As far as public education goes, it should not exist.

But then, what counts as teach about religion? How can one teach about history without teaching about religion, and religious disputes? Ignoring religion isn’t a possible solution.

The way it’s traditionally been is that religion is talked about in social studies, history and English/reading/literature, but it’s not taught. Context is given about religious upheaval, but religious tenets aren’t the focus. So religion isn’t taught in schools – unless you count part of the Pledge of Allegiance.

Sorry, but as a teacher of literature, you’ve just put an awful lot of my subject matter beyond the reach of my students. I can’t begin to teach British Lit, let alone World Lit, if I don’t instruct my students in some of the religious beliefs and attitudes that have been prevalent in different times and places. (Chaucer in particular would be completely unintelligible! And I suppose I’d have to drop Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Maxine Hong Kingston’s Warrior Woman from the curriculum entirely…)

An awareness of world religions is simply necessary in order to be an educated adult, in any case. American public schools will fail in our mission to give every student a basic orientation to the world if we leave out religion entirely… and we would leave the graduates of those schools even more vulnerable to propaganda such as that feeding our current wave of bigotry aimed at Muslims, or past waves of Satanic Panic aimed at our own communities.

Whole courses exist for the purpose of training teachers to navigate the boundaries between Constitutional teaching-about and unConstitutional teaching-of. Requiring teachers to know what they’re doing in this area is reasonable… issuing us yet another gag order is not.

My friend Charles is never an easy read. He is often rather simplistic in his stated views, but does have some reasoned thought behind them… and I hasten to add that I often disagree with him, as you do here (and I join you in that), and I don’t ever pull punches in telling him so.

To the general, topical point: public education in the US has a very difficult background. We focus on the high-profile atheist objection to mandatory prayer, but in my opinion it has its roots in a much earlier objection and rejection: Catholic parents finding that their children were forced to say the Protestant Lord’s Prayer. It fueled the blossoming of the parochial school system.

My sensitivity, informed by my wife’s long tenure in public schools and my own K-12 years in a district that was about 80% Catholic, focuses on the Christian tenet of proselytizing. It forms a sort of catch-22. Christians cannot escape equating teaching their religion with conversion as the goal with teaching about a religion. They simply don’t see the distinction, and refuse to trust that others — notably Pagans — not only draw the distinction but insist upon it.

You can’t teach about the abolition of slavery in Britain and the US without talking about Protestant Christianity. The Abolition movement was started by ministers in England and the Underground Railroad was supported by Quakers; defenders of slavery also quoted Bible texts. The debate over slavery is a good way to study the complicated relationship between religion and politics and might help students understand what is going on within Islam.

Anybody reading Abraham Lincoln’s speeches who isn’t familiar with the King James Bible is missing a lot.

The people who foster Islamophobia and the Satanic Panics did not get that way because secularism was taken to an extreme in public schools. They are the very people who have made religious education far too politically divisive to teach in schools because they abuse it at every turn to proselytize and force their views on everyone else.

I would agree that it is neither desirable nor possible to never speak of religion in school. One cannot have a serious discussion of the topics you mentioned without some context of the societies and forces (including religion) in play at the time.

That said, I have no interest in seeing any classes which are primarily about religion taught in our public schools below the university level. It is too polarizing and personal a thing and it will always, always become a pretext for proselytizing and privileging the majority religion. Religion in public schools has already done enormous damage to our education system (creationism). Our kids are lagging behind the rest of the world in core subjects like math and science. They don’t need to fighting the culture war on their learning time. The mischief caused by religious education vastly outweighs any benefits of good PR and face time which might be gained by Pagans, in my opinion.

Kids can learn the outlines of religious thought through history and social science etc. When it comes down to the nitty gritty of deeper theology, that’s what parents are for. By my own rough calculation, American kids have something north of 7,600 hours each year outside of classrooms. They have access to more information about religion on their phones and tablets than all of the top scholars and seminaries had when I was a kid.

I think it might help the discussion in general if it were agreed that assigning to write a profession of faith of any kind is a bad idea, whether it’s their own religion’s or not, …especially when it’s de facto assigning them to deny any faith of their own, in the case of exclusivist monotheisms, but really just in general. There’s no benefit about the language to pick a Muslim profession of *belief* just to teach about the pretty pretty Arabic script. 🙂

Wherever the line of ‘appropriate’ is, that’s way over it, though I doubt it was through any bad intent on the teacher’s part.