Earlier this year, when I was caught unawares without anything to read, I gave another try to an imposing work I had put off for way too long: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion.

I had attempted to delve into this iconic book a few years back, when my mother-in-law gifted me her ancient hardcover copy. Alas, on that occasion, I only managed to get through about two dozen pages before vacating the premises, more confused than enchanted.

To my defense, one has to admit that the Silmarillion is significantly less easy to read than the better-known Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. Written and edited as if it were an ancient chronicle, the Silmarillion reads like ancient history, medieval fiction or, at times, like particularly convoluted folklore. If you, like me, had problems getting through the prologue of The Lord of the Rings (yes, the one about the pipe-weed among many other things), you probably will have a hard time reading the Silmarillion.

This summer, however, things went much more smoothly. Maybe I have to thank getting more patient with age? Or the copious amount of ancient literature I now consume? Regardless, I quickly became enthralled by the pseudo-archaic mythology of the opening chapters “Ainulindalë” (“The Music of the Ainur”) and “Valaquenta” (“The Account of the Valar”) before immersing myself in the minute history-like writing of “Quenta Silmarillion” (“The History of the Silmarils”) and “Akallabêth” (“The Downfall of Númenor”).

While my enjoyment of the narrative had its lows and I constantly had to refer to the appendix every time some obscure elf was mentioned (think reading A Song of Ice and Fire, but 10 times the headaches), I overall had a great time with this odd, arcane volume. The intermingling tales of the deities, elves, humans, dwarves, and the forces of darkness they confront, all bewildering that they may be, function surprisingly well in concert and convey strong feelings of reverie, heroism, longing and mourning. To boot, the scale of the story told within the Silmarillion surpasses that of Lord of the Rings by such a degree of magnitude that the later feels comparatively much closer in spirit and significance to The Hobbit.

No, as a piece of literature, the Silmarillion, in the end, proved to be a quite worthy work and I am glad I gave it a second chance, and cannot but urge anyone who ever thought about doing the same to open its pages anew.

That said, the reason I am writing these words right now has little to do with the Silmarillion as a piece of literature. There probably exist thousands of reviews of this book and I don’t intend just adding one more to the pile. Instead, I would like to explore the Silmarillion as a work of mythology.

In-universe, the Silmarillion is a retelling of ancient myths of the elves of Middle-Earth regarding the origin of the world and their ancient history, gathered through various sources. Out of that universe, however, it was J.R.R. Tolkien, a towering philologist and expert in medieval literature, who penned those tales, and it shows.

As someone who has worked with medieval texts for many years (chiefly from Scandinavia), reading the Silmarillion gave me a truly eerie feeling. The diction, the rhythm, the figures of speech, the way the narrative is structured, and many more elements of the text were all reminiscent of actual medieval documents. Tolkien’s prose too, envisioned as a translation from Elvish, hit just the right spot between the stuffy Victorian English one can find in one too many public-domain translations and the flowery style found in The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit.

The disparate aspect of the work also mirrors medieval texts splendidly well. Each of the largely independent sections of the book reads a tad differently, and within the largest of them, Quenta Silmarillion, the main narrative is routinely interrupted to leave place for various digressive subsections which can feel a little out of place. This heterogeneous aspect corresponds perfectly to real-life ancient works, which often went through lengthy transmission and editing processes, transforming them into complex and composite products.

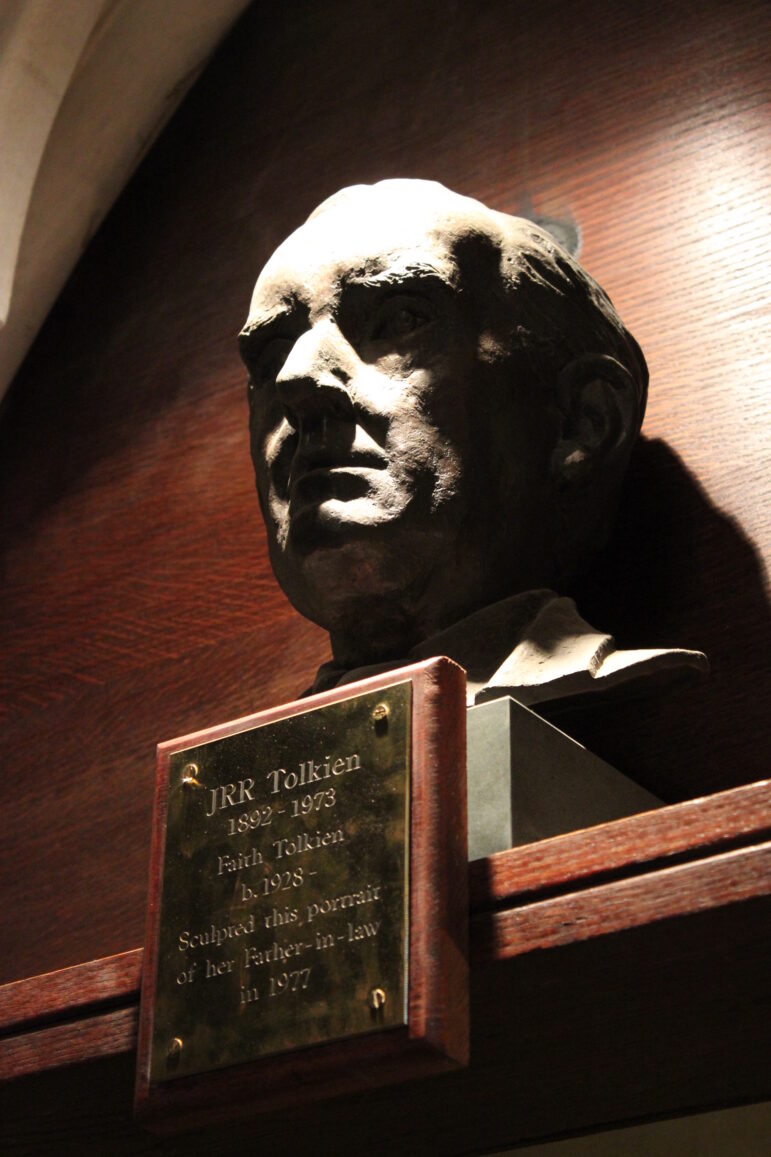

A Bust of J.R.R. Tolkien displayed at Exeter college in Oxford (picture by Julian Nyča, shared through CC BY-SA 3.0 license)

It does help, in that way, that in actuality, the Silmarillion went through such processes as well. With its earlier ideas taking shape as early as the mid 1910s, Tolkien’s lore took more than six decades (and the death of its author) to be shaped into a coherent whole. As was also often the case in the Middle Ages, this body of work was assembled by another actor, namely Christopher Tolkien, J.R.R.’s son and an accomplished philologist in his own right.

This combination of factors lead to the work we have today: a bluffing and enigmatic item which overall compares surprisingly well with the works of age-old literature, myth and history it was inspired by. This ultimate state of the book agrees well with Tolkien’s in-universe logic as well, where the Silmarillion was actually compiled, translated and edited by his hobbit protagonists Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, only to be copied further and ultimately discovered by Tolkien himself who translated it to English.

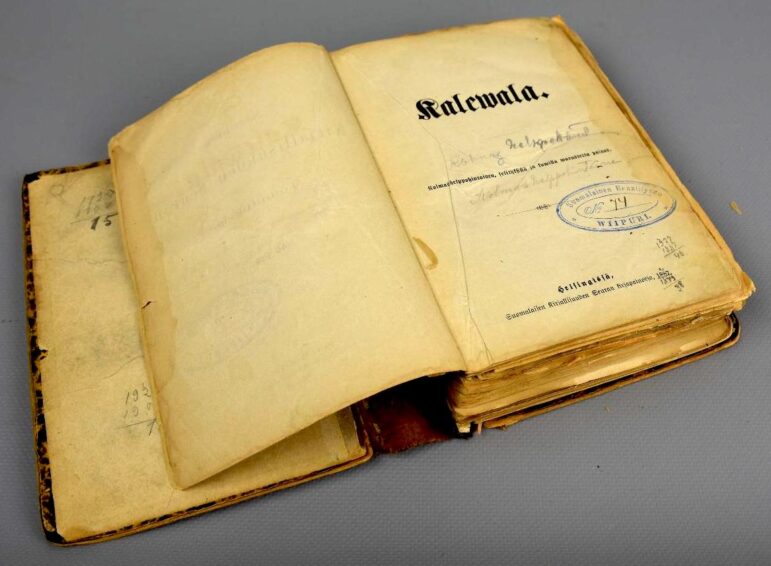

Out of universe, however, we know that in the early stages of his writing, Tolkien was inspired by a desire to endow his country and nation with an epic mythology of its own. A child of the 19th century, Tolkien was unsurprisingly influenced by the prevailing artistic and intellectual movements of his time. It is widely known, for instance that while still a young student at Oxford, Tolkien was greatly affected by his discovery of the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, compiled and edited by Elias Lönnrot.

The Kalevala and the language it was written in became such towering influences upon him that he borrowed numerous mythological elements from it and based his most important fictional language, Quenya (the ancient language of the elves), upon Finnish. But it was not simply the Kalevala, or any specific text that influenced Tolkien the most, but rather the spirit of the time that birthed those masterpieces: national romanticism.

![]()

We hate to keep asking, but it is serious. Costs have hit us too.

We are grateful to our readers for your support, however it manifests. Right now, we need readers who can help fund Pagan journalism to help us continue serving the community. This is the type of story you only see here. This is how to help:

Tax Deductible Donation | PayPal Donations | Join our Patreon

We remain one of the most widely-read news magazines within modern Paganism, and our reporters and columnists remain dedicated to a vision of journalism for and about our family of faiths.

You can also help us by sharing this message on your social media.

As always, thank you for your support of The Wild Hunt!

![]()

From the end of the 18th century onwards, Europe indeed witnessed a cultural revolution that saw the awakening of national and ethnic identities through politics, arts, and, not least, literature. All over the continent long-neglected idioms soon became the subject of academic study and symbols of national identity. Scholars, historians, poets, clergymen and politicians contributed to this movement by writing, compiling or editing texts in their native tongues.

This movement led to the publication of works that eventually became important symbols of national identity. As mentioned earlier, Finns elevated the Kalevala to their national pantheon. In Wales, the rediscovery of the medieval tales of the Mabinogion similarly impacted national identity.

A 1887 edition of the Kalevala (picture taken from the Lappenranta museum, shared through CC BY 4.0 license)

It is notable, however, that while the two works aforementioned were and still are considered to be of considerable antiquity, national romantics did not limit themselves to editing and publishing old works. Among the literary masterpieces brought forth by the national romantic awakening, many were modern works whose sole claim for ancientness were the motifs and narrative they presented. The Estonian counterpart to the Kalevala, the Kalevipoeg, although structured around old legends, was largely composed by poet Friedrich R. Kreutzwald. In Latvia, it was Andrejs Pumpurs who penned the national epic, the Lāčplēsis, using folk legends as inspiration for his largely fictional poem.

In some cases, utterly lacking ancient sources, or being unaware of them, national-romantic activists purely and simply forged documents. If there is still some debate about, for instance, the Ossian poems published by the Scottish poet James Macpherson, other more clear-cut examples are legion: there is the Oera Linda Book, a work presented as preserving ancient Frisian lore; the Chronicle of Rivius, a fictional account of ancient Lithuania; and the (in)famous Book of Veles, a text published in the 1950s that claimed to contain genuine mythical-heroic accounts of the ancient Slavs. None of these are authentically ancient texts.

One could say that, in the esthetic-intellectual vortex that was the national-romantic movement, the appeal of literary works was not necessary correlated to their authenticity. Collected folk tales, reworked legends, translated chronicles, modern works, and sometimes even completely fictional documents all could become the vector of national awakening, as long as they were well written and spoke to the soul of the nation.

A product of maybe the most extensive empire the world had ever seen, Tolkien never got to experience a truly national revival akin to that of smaller European nations struggling for independence and witness the (re)birth of the literary marvels born from it. Deprived of a unique and ancient mythology or a similarly obscure language to discover and revive, Tolkien simply put himself to work and crafted the legends, the songs, the languages, the heroes, and the lands he so acutely wished for.

Ultimately, whether he intended the Silmarillion to function as a national epic for England, Britain, the Anglosphere, or the entire world does not really matter all that much. What matters is that he succeeded. Inspired by the spirit of the time, which sought meaning, guidance and beauty in the ancient myths of the old world, Tolkien produced a grand tribute to the epics of old, a tribute that stood the test of time and acts now as a beacon for a new generation of esthetes and seekers.

When I started to read the Silmarillion, I expected to be entertained by literary prowess, to be hypnotized by the intricate verbiage of a master. Instead I was thrown back in time, to an idealized yet rugged world of legend that never was. When I finished the Silmarillion, I did not stand in awe upon what I had just read, I did not feel that I merely had the chance to experience a literary marvel.

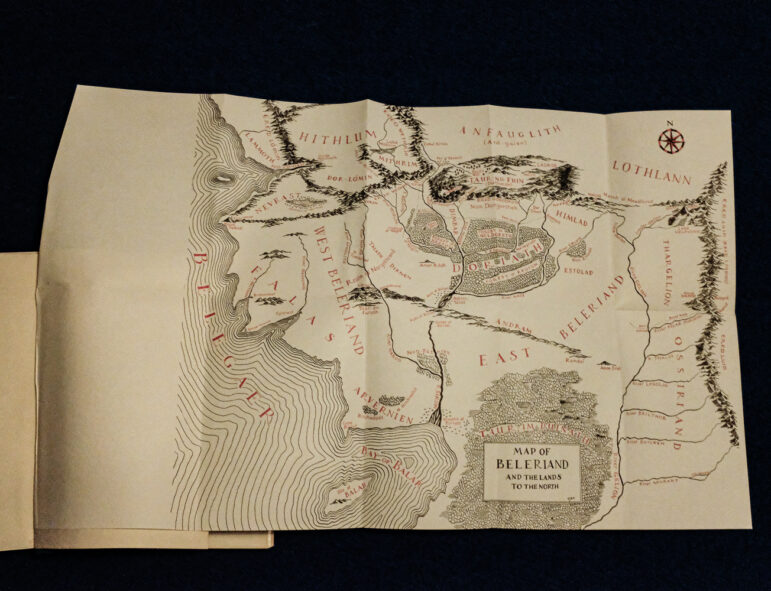

The map of Beleriand found in the first US edition of the Silmarillion (picture by the author)

No, As I neatly folded the map of Beleriand glued on the inside back cover for the last time (at least for now), I just felt inspired, and glad; glad because through my reading, I realized that the Silmarillion is more than just a book. While it is, outwardly, a beautifully written piece of literature, its very existence and striking publication history is also a testament to the force of creativity, the value of perseverance, and the capital importance of kinship bounds, in life, as well as in death.

Finally, the Silmarillion demonstrates maybe better than any other modern text the power and appeal of the age-old tales that have shaped our psyche and nourished our spirit. Not only does it renders homage to those, it so artfully emulate them in several key aspects that it beckons the question: could someone one day pen another epic text that even more ostensibly invokes the lore and spirit of the Old Religion?

With this unfinished, nearly apocryphal, admittedly fictional and motley construct of a text, Tolkien managed to open many doors, leading to the realms of esthetics, history, linguistics, and even spirituality. It is a quintessential inspiring work that ought to be read by anyone ever remotely interested in mythology and literature.

As for myself, upon finishing the book, I did not feel the desire to go back quite at once to Tolkien’s world, but rather to explore the works that so deeply imprinted in him. It made me remember that, somewhere in one of my many disorganized shelves should lie an old pocket-size copy of the Kalevala that I purchased many years back when I lived in the land of the thousand lakes. I think that instead of re-reading the Lord of the Rings trilogy, maybe I will give this venerable old paperback a try sooner than later.

This ability to inspire and enrich the reader is what make this book and the whole of Tolkien’s œuvre so engaging. I saw in it a deep reverence for the past, for heritage, and an unmatched appreciation for beauty, which is now leading me to a whole other mythical realm. Maybe someone else would have another, completely different experience reading it, but I doubt one could remain unmoved by its sheer magnificence; and this is why you should read the Silmarillion.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.