Today’s offering is from Lauren Parker. Lauren is a writer and visual artist in Oakland, California. She’s a graduate of Hiram College’s Creative Writing program and has written for The Toast, Strange Horizons, The Racket, Xtra Magazine, Catapult, and Autostraddle. She’s the winner of the Summer of Love essay contest in the Daily Californian, the Vachel Lindsay poetry prize, and is the author of the forthcoming deck of spells with Simon Element.

I’ve never been very good at spellbooks. Movies and TV shows promised that they would explain the great mysteries of the universe and unlock all of my desires, that I would find a singular book of guidance that would not only give me access to my desires, but directly tell me what I wanted in the first place. But when I was coming up in my practice, those spellbooks felt like reading stereo instructions.

From pocket books of candle magic to The Wicca Spellbook by Gerina Dunwich to five dollar esoterica on love spells in Borders, I was an applied failure. I understood magic to be this thing I should do, and yet it required a level of understanding that was outside the page. I bought so many books from end caps, looking for the great arbiter of secrets that would not only give me the spells I needed, but help me understand why I needed them.

Pages from a cookbook [Pixabay]

I started looking at cookbooks instead. Good ones, bad ones – I collected them from little free libraries and Ebay auctions, trading zines for typewritten broadsides of banana bread and under-the-sink wine. Where spellbooks that stunk hurt my feelings, bad cookbooks were funny, objects worth collecting. I wasn’t even particularly accomplished as a cook; I just wanted to have the opportunity to know what to do with the random vegetables that came from my community garden.

My great disconnect in the early years of my practice was the emotional connection to spell instruction. I couldn’t get there. I couldn’t get it. And I had read Gardner’s The Gardnerian Book of Shadows and Buckland’s Practical Candleburning Rituals and flipped through Silver Ravenwolf’s To Ride a Silver Broomstick: New Generation Witchcraft in the hopes of figuring out what I wanted and then attaining it.

When I moved to California a decade ago, cookbooks made it into my Subaru. Many regular books didn’t make the trip but the Little House on the Prairie cookbook, the Winnie the Pooh cookbook, and my grandmother’s cookbook made it all the way from New Hampshire with me.

I sat on the cookbooks and magical manuals like a dragon hoarding gemstones. I studied magic hypothetically, practicing weakly and feebly while feeling deep performance anxiety and having little success. I was also a bad cook. I struggled with focus, planning, and keeping track of the difference between boil and simmer. I went vegan, I went vegetarian, I went without dairy. I cut out ingredients that made me feel insecure. I wandered through the work with no focus or goal until I finally found the thing I wanted to achieve.

When in doubt, look at your ancestry, and my ancestor work started with a really big question: Why does half of my family seem to love really terrible food? I don’t mean terrible as a judgment on quality or some comment on calories, but genuinely bad tasting, “why would you do this?” food. No amount of sugar or salt could seem to save it, whether it was my grandmother’s macaroni recipe or my father’s well done burgers that were so tough you had to develop the jaw strength of a wolf to chew them. The greatest offender was a chicken and rice recipe that involved submerging whole drumsticks in a crockpot of tomatoey rice seasoned with cinnamon.

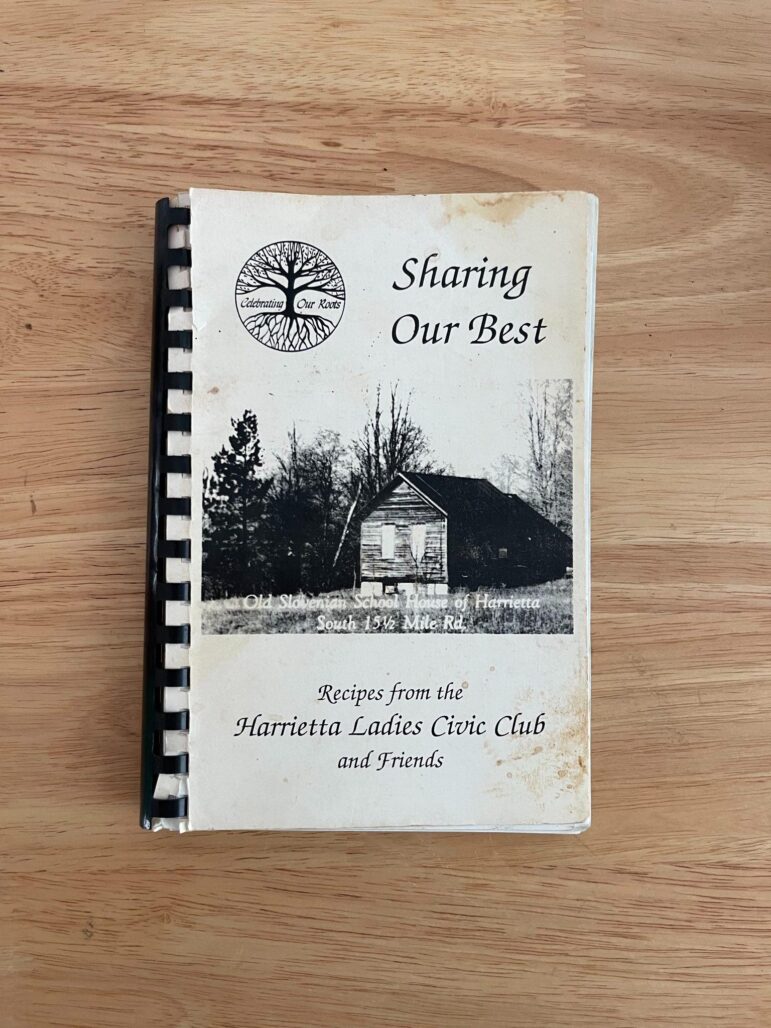

The book that contains this recipe, which I was convinced was being misinterpreted, is called Sharing Our Best: Recipes from the Harrietta Ladies Civic Club and Friends. It’s a cookbook that my grandmother, who died when I was five, gave my mother in 1990. The inscription is the only square of her handwriting that I have:

“July 1990, To Robyn, may you have a lot of enjoyment reading of Lauren’s heritage and now yours. Love, Mom”

It’s spiral bound, and the cover is in black and white, the typeface stark against the white pages. It’s a glorified pamphlet with introductions to the cookbook operating like love letters to rural Michigan. There is no internal artwork.

The cover to “Sharing Our Best: Recipes from the Harietta Ladies Civic Club and Friends” [L. Parker]

I have read this book cover to cover. My review is that the wonderful and fantastic and brilliant women of the Harrietta Ladies Civic Club (and Friends) did not know how to write a recipe. A bunch of the recipes in this tome, which was released as a fundraiser for an undeclared purpose, were clearly plagiarized from Betty Crocker – I can tell because those ones have pragmatically detailed instructions.

The original contributions, on the other hand, are absurd. As I flipped through it, it reminded me of some of the more unhinged advice from Uncle Buck. Adding jello to tunafish registered the same in my mind as putting a chintzy athame on the burner to get it red hot. Adding sauerkraut to spaghetti was equivalent to letting ants eat a frog carcass down to the bones. The cover features the Old Slovenian School House of Harrietta on South 15 ½ mile road (which I cannot find any trace of online) and the publisher is Fundcraft Publishing, Inc., which still exists.

The food was bad, the magic was bad, and both were written by people who had all of this knowledge they forgot to put down on the page. But food felt like the easier version of reading the more sophisticated grimoires. The troubleshooting of instructions, handwriting alterations, and crossing out some steps altogether made me more comfortable and confident in both the kitchen and in the sacred circle.

But one recipe author stuck out to me in the hundreds of pages. A person named Judy, who contributed nine in total to the cookbook, but displayed no talent for writing a recipe in any of them. There was something comical about reading a paragraph in a cookbook for Spaghetti Alla Judy [sic] where the first step is “make spaghetti according to the box.”

The first time I read it I said aloud, “Judy, come on.” I was immediately reminded of a candle magic book I had where the first instruction was to use homegrown wild henbane.

A woman standing in a kitchen in Austin, Texas, 1970 [Texas State Archives, Wikimedia Commons, public domain]

But Judy and I became friends. As I found out how to read the sparse instructions petered out by farm women and dusty occultists, Judy became my companion in the kitchen. I call her my kitchen ghost. Every time I burned the sauce or dropped the spatula, I would shout, “God damn it, Judy!” I could hear her laughing. I knew her in the corners of my mouth and the toss of my neck.

Judy became a tradition, and my kitchen poltergeist became an egregore for my kitchen Witchery adventures. I shared her with my Temple, I shared her with friends, and bragged about Judy far and wide. “Judy’ll take care of ya,” I said, “But sometimes you lose a slice of your thumb.” Judy was more helpful that she intended when she taught me how to read a box of noodles. I started reading Albertus Magnus with a better understanding of all the words, steps, and instructions that are not on the page, but between the words.

My cooking got better. I stopped burning the toast. I learned to scan a baking recipe and register that the bake time was too long for the ingredients and that I should add something wet to keep from creating rocks. I learned how to combine spices and how replacing the water base of cakes with tea gives them more dimension. I learned I hated saffron. I learned how to actually cook beans.

But here’s the thing: Judy isn’t dead.

My patron ghost is alive – at least according to Google. Her address and birth year are all easily searched through public records (to an unsettling degree for a woman who has probably not put anything about herself online). With the math I’ve done, she would have been contributing these recipes, the ones that fit in next to the ones of my grandmother and great grandmothers, in her 30’s.

I am in my 30’s.

I started to dive into finding out more about her, her surname’s meaning, if she contributed to any more books, if she had children, was married. I rammed into this poor woman’s life like a nosy maiden aunt, intent on discovering the most intimate parts of her without even bothering to send her a courtesy email.

Harrietta, Michigan, has a population of 151 people as of 2020, and sits in Wexford County, where most of my father’s family is from. Whether the town is Cadillac, Buckley, Manton, Haring Charter, or Harrietta, I probably have a cousin there – if not one cousin, then several. If not several, then come to the Moose Lodge where my dad spends his nights line dancing. Judy’s town as listed in the cookbook is five hours away in one of the many unincorporated townships that populate the midwest. I’m not sure why Judy would even care about fundraising in a cookbook that was raising funds for an organization over 300 country miles away. She must have qualified as “and Friends,” but she had nine recipes for the book. I want to buy every book from Michigan in 1990 to see if she contributed to them all. Maybe she was a font of food recommendations.

I dug more and more through webpages, trying to get as much information as possible. I didn’t know what to do with ancestor magic that had been funneled around a person who wasn’t dead. But in tracing my own familial history, I was now sifting through someone else’s. Like many magical quests, the instruction isn’t ancient, the ancestry is concocted, and I wasn’t the chosen acolyte at the altar of Judy of Bark River. Could something that meant so much to me be this shallow?

There are no photos of Judy online. There is no listed obituary (because she is very much alive). She’s referenced in one online article as a member of a regular friendship club that meets for birthdays.

While all of this information is technically public, I still feel that I’m invading a woman’s privacy. I’m slinking through digital space to find out more about a woman I technically made up and then killed, the personal folklore I told myself of a kindly older woman who really wanted everyone in her township to know how to make White Clam Linguini.

Where does ancestor work go when we’re too attached to the living? When the collection of people we want to protect us spiritually could be still living or even strangers? In the age of social media, are the altars to our digital dead waiting for us to call on them?

I hit a wall with Judy. There are whole chunks of life that I cannot fill in with the information I can dig up. Like Lake Superior, Google refuses to give up her dead. Even if they are still alive.

In the revision of my own pantheon, I have to face how much of religion is created. We built it and let it reflect our fears and hopes and truths back to us. Clearly I wanted a twinkling partner in culinary chaos, but I am faced with the reality of Judy. That she’s a stranger to me and owes me nothing.

There’s a level of disappointment in this for me. I will never know the real Judy, just the one I made up and then, technically, killed for my own bespoke pantheon. I have started to feel self conscious when I shout her name in my galley kitchen, no matter how bad the gas range burns. I’m heading into the holiday season. Who will peek over my shoulder when I add saffron to the soul cakes and spill the currents for the tea? Who will have a heavy pour of whiskey into the cider? Am I really going to have to make mistakes alone?

I will never know the dead occultists personally. I will never meet Bridget Bishop. Buckland is not coming down my chimney with insight. Albertus Magnus is never going to play with my cats (even though I am sure he would like them). But I cook good food. I learned how to read between the instructions, to add the flourish and flavor of magic. I know what to add to a spell jar to get what I need, and to put parts of myself into food and into crafts. I know how to sweep through my home and draw chalk protection under the bed.

Judy is the name of the god I built. She is all that I know instinctively and cannot access with my logical mind.

Despite all this, Judy is a part of the folk magic that’s made me. She wove an understanding of the brutalism of a tornado siren, of feeding a cow tobacco to settle the stomach, of trying to feed your family a version of Mexican food they might actually eat in rural northern Michigan. I don’t know what Judy’s life looks like now, but I still reach out for her whenever I toss too many dried currants in the soul cakes.

I hope she would like that.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.