TAMPA, Fla. – Coby Michael is someone who isn’t shy about discussing the path that he walks. Even among witches, the subject of baneful plants and maleficia can be a touchy subject at best. But frequently, such taboo subjects create their own liminality where you’ll find both the mature at work and the foolhardy at play. Coby represents the former.

One of the first things I noticed about Coby was the presence he carried about himself. In spite of working with plant spirits often associated with death and necromancy, he didn’t strike me as someone trying to put on spooky heirs. In fact, I felt an immediate kinship when we met in person over the summer. He is not someone who simply found himself on the path of the witch one day but was born upon the crossroads and the ensuing trials of life ensured that a witch he would be.

What also stands out about Coby is how compassionate he is. Rather than letting his life experiences embitter him, he genuinely seems to care and pay attention when conversing with people, whether they’re new and uninitiated or an old hand on the poison path, he relates to each person where they’re at.

When asked what his superhero origin story is, he was happy to roll with it. “Oh, it was a dark and stormy night that shaped me I would say. I’m a Witch, I’m a magical practitioner, Pagan, Heathen, all of those different things.”

He also said that growing up in the Midwest with a religious family shaped him in ways that maybe his family wasn’t expecting. With family members who were pastors and churches of various denominations, he found himself asking tough questions and not getting satisfactory answers, including around the deaths of loved ones.

“For as long as I can remember, things that I knew were wrong. In a lot of ways, I would get answers that would stir up more questions, more of a sense of fear and lack of control. I would ask a lot of questions about what happened and never was given an answer that really satisfied me and made me feel good,” he said.

While he said that he felt like he had a great childhood and was surrounded by a lot of loving family members, he also came upon the limits that a religious community imposes on you, especially as a gay person. Also at play were the effects of toxic masculinity and an alcoholic family member.

“I think in a lot of ways, I kind of wrapped up like my, my dad issues with my greater Dad issues — like issues with God — and issues with this patriarchal sort of system, and witchcraft kind of became my way of surviving and protecting myself for a long time,” he said.

Coby Michael [Courtesy]

While witchcraft provided him with a sense of protection, it naturally came with a cost within his community. “You start to get this constant demonization of, you know, witchcraft is evil. You shouldn’t be interested in spirits, that’s bad, or you’re a sinner, and you’re going to hell because you fall in love with with guys. And you take so much emotional, psychic, battering, and being as sensitive as I am, that at a certain point, all of that just gets turned outward,” he said.

So when he came upon maleficia, or the darker side of magick and witchcraft, it felt empowering. Coby describes that making people uncomfortable by demanding recognition and, especially, not apologizing for it was essential.

He was doing it to protect himself and the people he loves.

Eventually, Coby moved to Florida and found a budding interest in working with plants and herbs. “Initially, I was more interested in the folkloric associations. So I was still a plant practitioner, I was still a green witch, but I was drawing a lot of herbal folklore from different hoodoo and root work sources when it came to gathering plant magic correspondences. I just found the applications in those practices to be a little bit more practical,” he said. Books at the time that he found were written from a more Wiccan perspective lacked not only the baneful herbs but also would usually omit or gloss over any hexing work that he wanted to learn more about.

Coby said that most of his training has come from book learning and personal work but that he has taken some classes with different herbal schools and academies. But it was when he discovered what he described as 18th- and 19th-century herbals that he was able to take his work with poisonous plants and especially the nightshades to the next level.

“[They] actually have formulations and dosages and diving into some of the available information in the herbal pharmacopeia I was able to kind of reverse engineer my own formulas for creating things not necessarily for medicinal purposes, but more for creating those altered states of consciousness, but using the therapeutic dosages as kind of a safety zone to work with them,” he said.

Coby mentioned that, from when he was just beginning his journey, he discovered that, while still potentially deadly, the nightshade family was a little more forgiving to work with. He said that in spite of the dark reputation many of the plants hold, they’ve been an ally to humans both medicinally and ritually for thousands of years.

Among the many products that he makes, he also has a line of flower essences. Flower essences are basically where the flower of a certain plant is allowed to sit in a simple water solution and the energetic resonance of the flower is imbued into the water and then cut with alcohol as a preservative. No plant material is in the flower essence, just the energy signature of the plant. Most of Coby’s own work with nightshades, he admits, is meant to create physiological responses but he has found that in spite of that, flower essences have shown up for him in powerful ways when he needed healing support.

Working with the spirits of plants regularly, Coby identifies as an animist. His experience with them comes through as a sort of “wordless transmission of information,” that he finds happens whether you’re growing a plant, working with a flower essence or even making a charm bag.

Most think that you have to be a green thumb or actively sit in the presence of a living plant to commune with its spirit but “that’s not always possible, or desirable. Not everybody wants to be a plant grower. For me, personally, I’m more of a wild grower, like I would much rather plant the plants outside and let them do their own thing,” he said.

Often, he said, the best way to work with the spirits of baneful plants is in the same way we work with deities. While we may have a representation of a god or goddess, we invite the spirit of that deity to imbue their energy into that representation. We can do the same with plant spirits, he said.

“So what I’m coming to recently is trying to connect people with the idea that plants like wolfsbane, mandrake, deadly nightshade, they are such historical figures, they have such a prominent role in plant history in medicine, and religion and magic and all of these things they’ve got these mythological associations that we can trace back to their origin myths. And so in a lot of ways, these low dose or power plants or master plant spirits, whatever you want to call the poisonous plants, they are a lot like deities,” and we’re able to call those spirits in, he said. In this way, we can summon the plant spirit into our ritual spaces without requiring the living plant itself to be present.

Working with plant spirits, or spirits in general, can be treacherous work that can lead to harm for yourself but something not often considered is the harm that you can do to the spirit by having a relationship based around extraction or exploitation rather than mutual respect. Coby said that he sees dangerous trends around the current psychedelic revolution or renaissance in magickal as well as non-magickal communities. And while he understands the desire to connect with something larger than yourself or the desire to heal and expand consciousness, there are some clear negatives.

“I think that there is a darker side to it, just the issue of profitability and who’s making the money? Where’s the money going? The sustainability of the plants, but also the traditions, the indigenous people, where are the plants coming from? How are they being harvested, and, you know, there are people doing Ayahuasca ceremonies in places that are thousands of miles away from its homeland. And that’s a plant that has been in the same part of the world for millions and millions of years, and really hasn’t moved into other places,” he said.

Beyond those very real issues, he questions how much true healing is coming through the plant medicine, versus giving the consumer an afterglow effect that they’re misinterpreting. He said, “You sort of get this spiritual bypassing symptom where now we’re not we’re not going to work on any of the childhood trauma or the abusive relationship or you know what led to the addiction in the first place,” and instead find a sort of brief, chemical tune-up.

These are issues that are not easily unraveled, either. While the ethical questions grow around sourcing and monetization of what amounts to alternative treatments for mental health, it’s hard to argue with someone who is experiencing real relief from symptoms associated with PTSD, anxiety, or depression.

At the moment, Coby worries about what’s being left out of the conversation. “I think that the whole spiritual side of it kind of gets forgotten.”

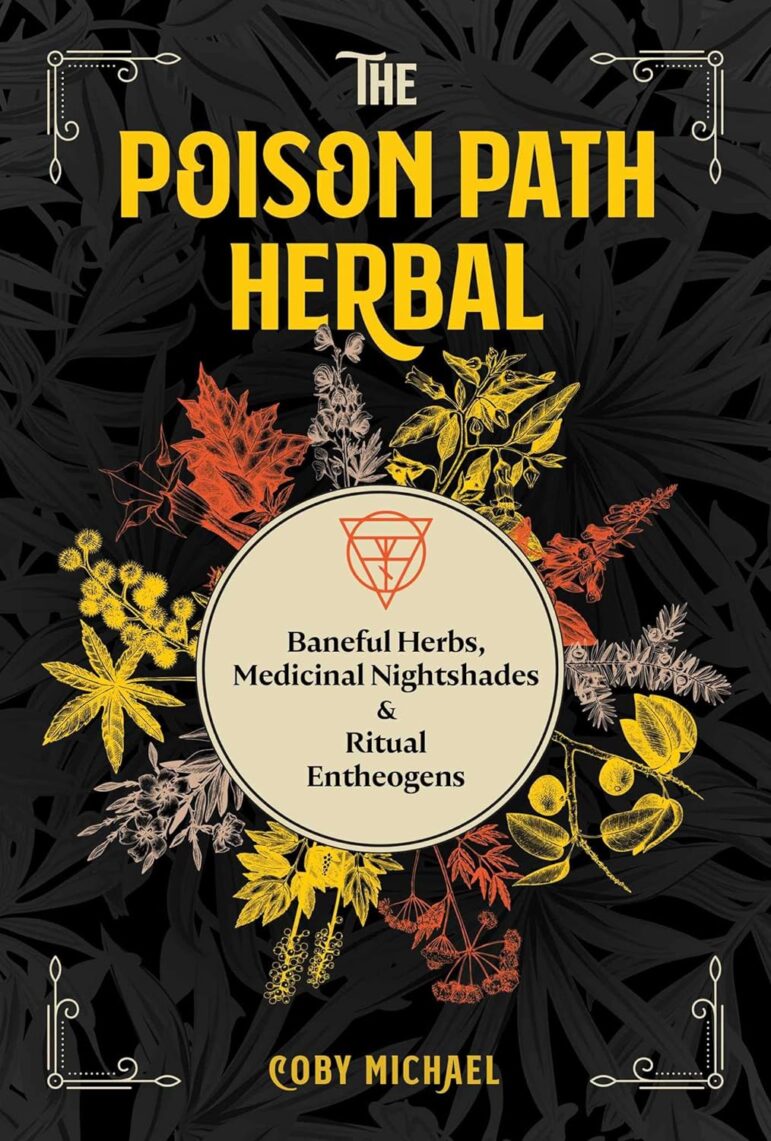

Coby Michael’s book with Ivo Dominguez, Jr. and a number of contributors, Leo Witch was recently released by Llewellyn Worldwide and his book The Poison Path Herbal: Baneful Herbs, Medicinal Nightshades, and Ritual Entheogens is published by Simon & Schuster and available wherever books are sold. His annual online conference, Botanica Obscura, will be March 8 – 10.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.