TWH – Research published last week in Biological Reviews by scientists at Queen’s University Belfast and the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague suggests that the global loss of wildlife is accelerating. The researchers said that “The widespread loss of biodiversity has reached unprecedented degrees of ecosystem degradation at rapid timescales” noting that just under half of the planet’s species are experiencing swift declines in their populations.

Late last year, the Conference of Parties 15 (COP 15) took place in Montreal. This United Nations Conference focused on preserving global biodiversity. COP15 produced the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) with four goals and 23 targets to be reached by 2030. The first goal of the GBF would require reducing the rate of extinction tenfold for all species by 2050.

As TWH reported previously, under one target, a country would have to legally protect large parts of its territory. Countries would have to legally protect 30% of their land area by 2030. They would also have to protect 30% of their inland, coastal, and marine waterways by 2030. At present, only 17% of land and 10% of marine areas are under protection. Another measurable target would focus on cutting subsidies for materials that harm biodiversity. By 2030, it would phase out $500 billion per year in subsidies that harm biodiversity and require subsidies for materials that would benefit biodiversity.

The new study underscores the importance of those targets.

The researchers noted that habitat loss and the destruction of wild areas by humans was the main driver of the problem. The study authors refer to that human encroachment and urbanization as leading to an “Anthropocene extinction crisis,” a human-driven process that is resulting in “a rapid biodiversity imbalance, with levels of declines (a symptom of extinction) greatly exceeding levels of increases (a symptom of ecological expansion and potentially of evolution) for all groups.”

Amphibians are seeing large population declines. [Photo credit: MJTM

The researchers analyzed data from over 70,000 species to find out whether their populations have been steady, declining, or growing over the last decade. The data were gathered using the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List conservation categories. “These categories are based on the assessment of multiple species features (e.g. geographic range size, population size, and levels of fragmentation: IUCN, 2012) that combined suggest the most likely level of threat. At the time of assessment, species can be classed as ‘threatened’ with extinction [categories Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), Critically Endangered (CR), Extinct in the Wild (EW)], ‘non-threatened’ [categories Least Concern (LC), Near Threatened (NT)], Data Deficient (DD) or unassessed (NA).”

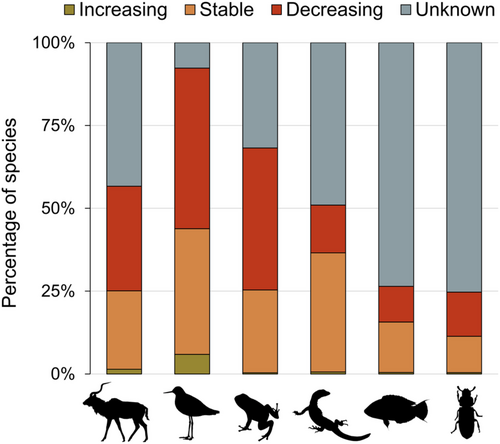

The list spans amphibians, birds, mammals, fish, insects, and reptiles.

They also survey habitats. “Habitats were classed as one of the following categories: terrestrial, freshwater, marine, terrestrial and freshwater, terrestrial and marine, freshwater and marine, terrestrial freshwater and marine. These were then grouped into two taxonomic groups: vertebrates (mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fishes) and insects. Proportions of species reported for each habitat … were calculated for exclusively terrestrial, freshwater and marine species.”

The study also noted that human-driven habitat loss was not the only factor in the accelerating loss of species. They found that the changing climate pattern was another culprit. “Geographically, we reveal an intriguing pattern similar to that of threatened species, whereby declines tend to concentrate around tropical regions, whereas stability and increases show a tendency to expand towards temperate climates,” they wrote.

The study found that nearly half of the species have been experiencing rapid population decreases. The study reported that 48% of species surveyed are experiencing declines, 49% remain stable, and less than 3% of species are showing population increases.

The study also noted the limitations of the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. It classifies only 28% of species as under threat of extinction. The researchers say that their data shows that declines toward extinction are still occurring in 33% of the species currently classified as “non-threatened” by the IUCN Red List.

Percentage of species per taxonomic group which have decreasing, stable, increasing, or unknown/unassessed (NA) population trends. Each group is represented by a silhouette from left to right; mammals (N = 5969), birds (N = 11,162), amphibians (N = 7316), reptiles (N = 10,150), fishes (N = 24,356) and insects (N = 12,161). Data were sourced from the IUCN Red List (www.iucnredlist.org). via Biological Reviews

The researchers noted that “overall, these observations show that only a small number of species show increasing populations and that a high proportion of species with decreasing populations within groups is the norm across animals for which these data are currently available.”

One of the authors of the study, Daniel Pincheira-Donoso explained that the results are not about whether species are presently classified as threatened, but rather whether their population sizes are decreasing rapidly and progressively. Declining trends in species populations over time are, of course, a serious precursor to extinction.

The researcher concluded that we have “major deficiencies” in our understanding of what might be happening to species. They added that their analysis “provides a considerably more alarming picture than the estimates derived from the use of IUCN Red List conservation categories of threat.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.