Generation X is large, it contains multitudes.

We are latchkey kids. Star Wars early adopters. Arcade patrons. Atari devotees. Punks and preppies. Hip-hoppers and headbangers. Break-dancers and goth rockers. After school cartoon watchers. MTV fanatics. John Hughes subjects. Dungeons & Dragons devotees. Ninja wannabes.

We are also the kids who experienced the hard-wiring of home computers into our homes and schools. Personal computers, as they were called, seemed to sprout up like mushrooms everywhere we looked.

My dad brought home a strange device that looked like a typewriter merged with a TV set. It was a dumb terminal that had to be hooked up to his university’s mainframe via a landline telephone call in order to do anything. I was absolutely thrilled to play a text-based Star Trek game and (when no one was watching) type rude responses to an automated computer therapist.

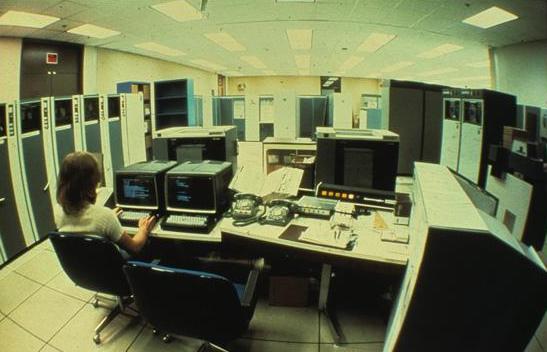

U.S. Geological Survey computer lab in 1980 [Public Domain]

My school suddenly had a computer lab of Apple IIs, and we learned to write programs and design graphics in a magical new language called BASIC. We saved our sets of if-then and go-to statements on, of all things, audio cassette tapes. We tried to draw spaceships with thick and unwieldy but wonderfully glowing low-res lines and felt the liberation of eventually moving up to the sophisticated thin high-res lines. The bully kids got in trouble for printing what they called “French postcards” – pages full of letters, numbers, and typographical symbols that looked like naked ladies, if you held them at arm’s length and squinted really hard.

We made the data storage transition from cassette tapes to enormous floppy disks that didn’t feel at all floppy. We were amazed as they shrank into more compact and even less floppy versions. We were astounded by the wonders of the CD-ROM and the seemingly endless storage of the Zip drive.

We watched computers get smaller and smaller and the graphics get clearer and clearer. Somehow, we remained married to the telephone connection, even as we moved through waves of new technological developments.

Meanwhile, telephones went from heavy rotary devices we received from the one and only phone company to smaller oblong devices with push buttons but still connected by long and coiling cords to the cradle plugged into the wall. We experienced the mad sense of liberation that came with cordless phones and the freedom from wondering what wonderful calls we missed with the introduction of the answering machine. We felt that we really were living in the future when the first flip-top mobile phones were made available. No more using a school phone or pay phone to call our home answering machines and check for messages!

We wrote electronic mail messages, sent them out over the phone line, then repeatedly logged in to see if we had any responses to download and read. When early mobile phones let us send and receive text messages, it was as if we had stepped into a science fiction future imagined by long-ago telegraph users.

We were there at the beginning of modern social media, typing away on newfangled websites like GeoCities. In the deepest depths of my own personal nerditude, I jumped on the “tribute page” bandwagon and designed one for the holographic doctor on Star Trek: Voyager. It was a different time.

All of these developments seemed to be part of an endless upward spiral, but they followed a logical pattern of development that appeared linear and basically comprehensible.

Then the smartphones arrived.

Now, we really were in the future. We had actual Jack Kirby Mother Boxes in our pockets. We had entered the world of Philip K. Dick’s Ubik, in more ways than we could imagine. This was even better than a Dick Tracy two-way TV wristwatch!

The little computer in our pocket was refined along with an array of new social media platforms. GeoCities was abandoned for MySpace, and MySpace was abandoned for Facebook. The various outlets began to distinguish themselves from each other, often by, paradoxically, stealing concepts and functions from each other. This was all a bit confusing but also exciting to dive into.

Viewing vs. seeing

Way back in 1957, Isaac Asimov published the science fiction mystery novel The Naked Sun. When I read it in those early days of home computing in the 1980s, one scene in particular burned itself into my memory.

The Earth detective Lije Baley makes a trimensional call to Gladia Delmarre, Solarian widow of a murdered fetologist (apologies for the 1950s hard SF lingo). When she enters the holographic video chat, she’s just coming out of an air-dryer after a shower and is completely naked. Bailey literally jumps out of his chair in shock, and Gladia calmly explains why – in her culture – nudity on holographic calls is no big deal.

“I hope you don’t think I’d ever do anything like that, I mean just step out of the drier, if anyone were seeing me. It was just viewing.”

“Same thing, isn’t it?” said Baley.

“Not at all the same thing. You’re viewing me right now. You can’t touch me, can you, or smell me, or anything like that. You could if you were seeing me. Right now, I’m two hundred miles away from you at least. So how can it be the same thing?”

Baley grew interested. “But I see you with my eyes.”

“No, you don’t see me. You see my image. You’re viewing me.”

“And that makes a difference?”

“All the difference there is.”

It still amazes me that Asimov had his finger on a key component of social media consciousness, a half-century before Facebook and the iPhone.

From the nude trimensional call to saying “poopyhead” to a 1980s mainframe therapy robot to people publicly revealing the most intimate details of their personal lives on today’s social media, there has been a disconnect between what we will say and do in real life and online.

1925 illustration imagining video communication of the future [Public Domain]

Anyone who has participated in any web-based subcultural community knows this. Whether it’s music fans, comic book readers, movie watchers, Tolkienites, stamp collectors, or Pagans and Heathens, participants will often portray themselves in ways directly opposite of their day-to-day characters and will regularly say any old thing that pops into their heads, no matter how offensive or confrontational.

Twenty years after the founding of Friendster, so many web surfers (as internet users used to be called) still act as if the things they broadcast online aren’t really real, while simultaneously investing their virtual relationships with pseudonymous strangers with the deepest devotion and emotion.

On the positive side, this psychology enables a freedom of interaction that may not normally be possible, for a host of reasons. The geographically isolated, culturally stranded, grievously abused, and simply lonely can find a community of minds that enables them to experience a form of camaraderie that can seem more real than the real.

On the negative side, the disconnect from reality somehow serves as permission for many to spew the most viciously violent bile that their inner darkness can muster.

Since publicly diving into the world of Ásatrú and Heathenry – modern iterations of Old Norse and Germanic religions – with the beginning of The Norse Mythology Blog over a dozen years ago, I’ve been the object of a long string of insanely violent threats. They often come from people who will post a cute kitten photo immediately before or after threatening to break my hands or slit my throat. A Pagan college student once told me that “death threats are just how my generation expresses itself.” Yikes.

Usually, it’s something I’ve written at The Wild Hunt that gets nominally normal Neopagans all in a murderous tizzy. Suggesting that all-white Heathen organizations with all-white leadership hosting all-white events in which a white celebrant leads white participants in hailing white ancestors may actually have some basic assumptions in common with the neo-völkisch groups they publicly disavow has led to outwardly friendly “inclusive” practitioners including endorsements of violence in their online responses. Daring to do so has gotten me bitterly denounced as a heretic (!) deserving of a good, old-fashioned beating.

A Heathen I had met numerous times in person was so enraged by one of my columns that they sent me a social media message threatening to smash my head in with a brick. This unhinged threat of violence came from someone who, in real life, was incredibly and awkwardly shy – absolutely not someone capable of looking you in the eye and saying they will murder you. As in the Asimov novel, there’s a sense of distance when communicating online that emboldens even the meekest mice to act like rabid rats.

Which brings us to Twitter.

Twitter in past tense

I don’t think anyone would claim that, up until now, Twitter had been perfect. It absolutely had not, but it sometimes got important things right.

On a micro scale, Twitter sometimes worked to protect users. Twitter administrators permanently banned a self-declared but anonymous Pagan who was so incensed over one of my Wild Hunt columns (as per usual) that they tweeted out a disturbingly specific statement about stabbing me in a parking lot.

Early testing of Twitter tweet system [Public Domain]

That ban was nice, but there have been so many instances of harassment of and threats of violence against so many people from so many communities that simply received the “this doesn’t violate our terms of service” response from Twitter that it was a total mystery as to what level of violent threat was needed to trigger decisive action from the company.

In those many frustrating cases, the block button was incredibly helpful. Unlike on Facebook, where I first learned the term sock puppet due to Heathens blocked for general vile grossness immediately creating multiple new accounts specifically to continue sending nasty direct messages, Twitter had a block feature that generally kept wingnuts from sliding back into my DMs.

On a macro scale, Twitter provided a platform for people who had previously had little or no access to telling their stories through mainstream media. News and opinion outlets centered on feminist, LGBTQIA+, Pagan, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Native American, African-American, and a host of other perspectives appeared in the feed side-by-side with corporate outlets such as CNN and The New York Times.

This democratization of presentation enabled interaction between the high-and-mighty and the rest of us. It became obvious that politicians like Donald Trump read replies, even though many media personalities like Chris Hayes usually only responded to others who shared their blue-checked “verified” status. Unlike most of the rest of social media, Twitter was a place where the disenfranchised could directly clap back at the powerful, fact-checking their falsehoods in real time for the world to see.

Maybe even more importantly, the intersection of sophisticated smartphones, widespread internet access, live video broadcasting capabilities, and Twitter’s openness of access allowed an enormous audience to watch history happening as it happened, without the filtering process of for-profit news broadcasters.

In early 2011, the Twitter hashtags #Egypt, #Libya, #Bahrain, and #protest were used by the protestors of the Arab Spring as they stood against oppressive regimes. The Arab Social Media Report of the Dubai School of Government emphasized that Twitter had played a key role in the massive uprisings that we could all follow across our feeds. Even as the activists coordinated via social media, we could follow their progress moment by moment from thousands of miles away.

In 2014, participants in the Ferguson, Missouri protests of police violence against African-Americans used streaming video features on Twitter to broadcast raw, in-the-moment documentation of the actions of militarized police forces. Given that corporate media reporters so often serve as simple stenographers for police chiefs giving the official account of their own officers killing Black citizens, it was a sea change when worldwide viewers could watch police in Judge Dredd armor shooting tear gas at protestors while deploying armored military vehicles and aiming sniper rifles at them.

There was an immediacy to the constantly updating story reported from the ground level that spread out and affected local and national dialogue. I repeatedly stayed up until early morning jumping from feed to feed on Twitter, then engaged in divinity school discussions of the events only hours later. These conversations quickly made plain how few Black voices there were in our classes, especially when African-American graduate students adjusted the discussion to include examination of the university’s own private police force patrolling the surrounding neighborhoods and harassing Black residents.

Twitter mattered, in many ways. Now, that Twitter is receding in the rear-view mirror.

Elon Musk has entered the chat

This fall, the richest person on the planet bought Twitter for $44 billion (with a b). For comparison, the Ricketts family bought the Chicago Cubs for $900 million (with an m). Google bought YouTube for $1.65 billion. The Walt Disney Company bought Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion.

There’s an annotated timeline of the Elon Musk Twitter takeover here. To get the funds together, Musk sold $8.5 billion in Tesla shares, picked up over $7 billion from investors, accepted $35 million in Twitter shares from the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, and took on a bunch of bank loans. In other words, there are a whole lot of hands pulling the social media strings besides his.

“We only lend to the rich” by Henry Gerbault (1890s) [Public Domain]

The company was immediately decimated. A large number of staff members quickly quit, many moving over to Google and Meta. Musk fired the entire board, top-level executives resigned, and thousands of workers were axed. The remaining employees continue to leave or be fired en masse.

Suddenly, anyone with $8 and a credit card could purchase a blue “verified” check, and chaos ensued. Fake accounts pretending to be celebrities, politicians, and corporations proliferated, some of them quickly cratering the stock price of the companies they imitated. In response to this mess and to the sudden surge in uncontrolled hate speech, advertisers “paused” their Twitter spending across the board.

Whatever motivations have driven Musk to demolish Twitter and take Tesla and his own net worth down with it, his embrace of hate speech is clear. Since taking over the website, he has repeatedly tweeted his support for the far right and opposition to “woke propaganda.” He’s reinstated the account of Donald Trump, shut down in the wake of the January 6 raid on the Capitol. He’s now announced that he’s granting a general amnesty to suspended accounts, which means we can expect the return of Alex Jones, Milo Yiannopoulus, Katie Hopkins, Steve Bannon, David Duke, and the Pagan person who said they were going to stab me in a parking lot.

Just as it’s unclear what Musk’s motivations are and what favors are expected from his domestic and foreign suppliers of purchase funding, it’s up for grabs what will survive of Twitter as it has been until now. A self-declared “free speech absolutist” and habitual poster of tasteless jokes who declared “comedy is now legal on Twitter” after his takeover, Musk has moved quickly to shut down accounts that publicly tease him. What will he do when his cash and stock sources want him to ban accounts that, for example, criticize the rulers of Saudi Arabia or use Twitter to organize and broadcast protests against it?

This is all such a strange convergence of contemporary U.S. hero-worship of raunchy inheritors of vast family wealth like Musk and Trump with the ongoing manipulation of public discourse by sometimes shadowy investors who are either led by attention-hungry individuals like Musk or use him and his kind as public patsies. By adopting the tried and true American marketing language of freedom and free speech, they rally ready troops who giddily cheer them on, even when (or especially when) they’re shutting down accounts of those who criticize them.

Gen X’ers who have been here since the advent of home computers know that no tech is here forever. In the end, both sides lost the Atari-ColecoVision wars. The glorious CD-ROM was killed by the widely accessible website just as MySpace was murdered by Facebook.

Twitter has had a solid run of over 16 years. When it ends, it ends. A host of would-be successors have sprung up and gained early adopters, but no clear choice has yet been crowned by the masses. I remember being flabbergasted when national news outlets began putting tweets on-screen and reporting them as news. Things change, and there will be a new consensus location someday soon.

I hope that it will offer a similar setup allowing the powerless to take the powerful to task. I hope that it will place articles from minority media on equal footing with corporate news outlets. I hope that it will allow nonviolent criticism of the wealthy and powerful to be shared widely, even when it directly targets the wealthiest investors. I hope that it will be a free resource for those around the world taking on the dangerous task of protesting oppressive regimes.

Most of all, I hope that it is able to restrain the nauseating hate and disgusting violence that I pray won’t be the ultimate legacy of all these decades of technological development.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.