“In the Shahnameh, the national epic poem of Iran, there is a tale of an evil king called Zahhak who rules over Iran and kills young men and feeds their blood to the snakes laying on his shoulder. Then, a young man named Kaveh rises against him and makes a flag as a symbol of his revolt against the evil king. Lately, more and more Iranians have started referring to [Iran’s supreme leader] Khamenei as Zahhak and taking this flag to the streets.” -“Mitra”

TEHRAN – While the ongoing social unrest in Iran and its subsequent repression have received significant coverage the world over and shed a light on the plight of Iranians, the religious component of the conflict has not garnered the attention it deserves, at least according to one Iranian Pagan who reached out to The Wild Hunt to share her story.

Requesting to be referred to only as Mitra (“a common Persian girl name and a goddess name”), the interviewee had been in regular contact with a member of TWH staff for years when the current protests began, and she expressed her desire to share her perspective on the dramatic events currently unfolding.

Rejecting Islam and embracing Paganism, Witchcraft, and polytheism was already a crime punishable by death in a country run under Iran’s interpretation of Islamic sharia law. The penalty for communicating with foreign media is no less benign, even more so in the current context.

Despite this risk, Mitra communicated to TWH throughout the first week of the internet shutdown orchestrated by the Iranian State. Although TWH attempted to reestablish contact and obtain updates on the situation on the ground later, this proved to be unsuccessful. We therefore acknowledge that some of the information presented in the present interview might not be up to date.

We nevertheless hope that Mitra’s message might resonate with our readers and help them understand the lived realities of Iranian Pagans and other non-Muslims during these dramatic times.

When asked about her spiritual beliefs, and how they came about in the context of one of the few theocratic countries in the world, Mitra describes how her cultural heritage and family history came together and shaped her worldview.

“Back then, in the 90s and early 2000s,” she says, “everyone was under heavy surveillance in schools and religious enforcement happened via regular Muslims who worked voluntarily for the government. The number of non-believers was a minority, and all of them hid their beliefs. However, my father knew the pre-Islamic history of Iran very well, and believed in Zoroastrianism in his heart; he was the one who didn’t let me fall for the propaganda at school.

“Now, I don’t follow a specific book or religion,” she continues, “but a collective of ancient spiritual beliefs which include pre-Islamic beliefs of Iranians, especially as a way of keeping the heritage and culture alive.”

Mitra comes back again and again to the question of religion and how central it is in separating average Iranians from their ruling class. The Iranian constitution of 1979, adopted following the revolution which ousted Iran’s monarch, gave the Shiite clerical class near total control and legitimacy over state affairs. But according to Mitra, such orthodoxy conceals a widespread disdain for religious rule among Iranians.

“Islam is the core of the current regime,” says Mitra, “and their rulings are all derived from the Quran word by word, and everywhere you go, you see constantly Islamic symbols and propaganda. For example, you can hear the prayers being said very loudly from all the mosques in Tehran, but inside, there rarely are actual prayers taking place, and most are actually closed to the public.”

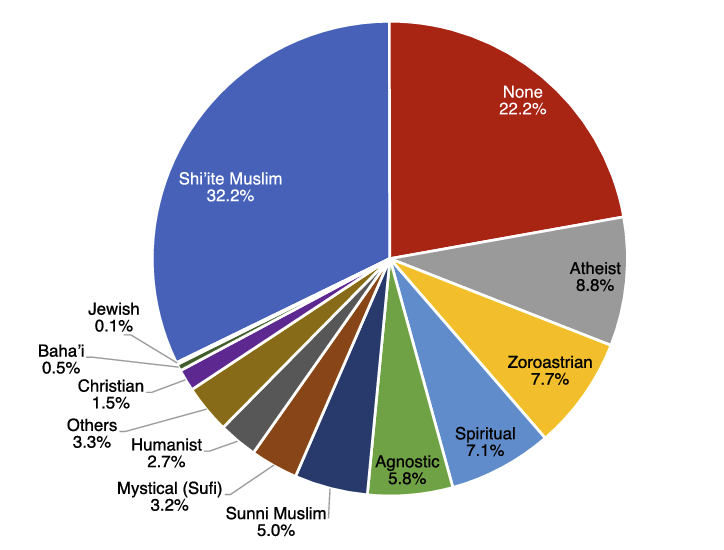

Mitra’s words echo the results of a widely-publicized online poll conducted in 2020 by the Netherlands-based research institute GAMAAN (Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in IRAN). Helmed by Iranian scholars based in the West, the group was able to reach tens of thousands of Iranians living in Iran and question them about various aspects of their relationship to faith and spirituality.

When the final report was published, its results were discussed far and wide, both within and without Iran. While earlier polls had constantly depicted the Iranian society as being dominated by Islam, the GAMAAN survey painted a completely different picture: a nation which, despite the theocratic nature of its ruling class, displayed a plurality of attitudes toward religion more akin to Western countries than other Middle Eastern ones.

The main figure from the GAMAAN poll from 2020 (gamaan.org)

Although the results of the poll were quickly dismissed by the Iranian authorities, its results were widely seen as reliable by swathes of Iranians on the internet, including Mitra herself. “I saw the poll,” she says, “but I think that A LOT has changed since 2020 and now the number of non-Muslims has risen significantly.”

One point she and the GAMAAN poll agree on is the seemingly rapid and recent generational decline in adherence to Muslim values in Iran. “In Iran, some families are made up of believing Muslims,” says Mitra, “but still you can barely find a family where everyone is a believer. The newer generations of parents strictly raise their children without Islamic culture. These parents are the generation who themselves were raised by strict Islamic rules of the early 80s, which looks a lot like a Handmaid’s Tale universe.”

Her experience appears to be reflected in the GAMAAN poll, where 60% of responders described their childhood religious family environment as believing in the Islamic god and religious, while 68% stated that religious prescriptions should be excluded from legislation.

Another aspect of Iran’s evolving religious landscape is the shifting of people’s spiritual affiliation. According to Mitra, criticism of government-mandated Islam began in earnest on social media platforms and other forums in the early 2010s and quickly experienced an exponential rise, despite government repression, which routinely claimed lives.

“People gradually found out there are millions of others like them inside Iran,” Mitra says, “and they started talking openly. Gradually, it was no longer scary to talk in those communities because most people were not really against you.”

Although many of those who engage in this clandestine online milieu routinely express disdain for religion in general (as reflected in some of those groups’ names such as “Community of Atheists and Agnostics of Iran” or “Republic of Non-Believers”), for individuals stemming from an Islamic background, conversion to other faiths, although punishable by death, appears to have become more common in recent years.

As shown in the GAMAAN poll, despite a majority of responders expressing various degrees of hostility towards Islamic practices, the majority (78%) responded that they believed in the Islamic god, and 5 to 8% of responders (depending on the demographic) reported switching religions.

It is Mitra’s understanding that while the origin of this phenomenon can also be traced to the early 2010s, it gained significant traction only in recent years. “Even before the early 2010s,” she says, “some people were converting to Christianity as a way of escaping Islam, but all of them had to flee the country. Later, some unofficially converted to Zoroastrianism or pre-Iranian religions as well, and as time passed, this movement became stronger, as more people wanted to distinguish themselves from Muslims.”

While the GAMAAN poll does not have much to say on the topic, and relevant research remains extremely limited, Mitra believes that a significant share of Iranians reject Islam by reconnecting to pre-Islamic myth, culture, and practices. She especially stresses the popularity of ancient Iranian seasonal feasts.

“Our New Year celebration,” Mitra says, “which has many rituals starting from the last days of winter and followed by the start of spring, is the biggest nationwide holiday and is celebrated on the exact hour, minute, and second of the spring equinox. The second-biggest nationwide holiday is Yalda Night, which is celebrated at the winter solstice and has its own tales and rituals. It’s about celebrating the longest night of the year as the light finally overcomes the darkness.”

Free Iran Demonstration, Washington, DC, USA. Photo by Ted Eytan on flickr.com. (CC BY-SA 4.0) flickr

When TWH asked Mitra about the ongoing protests and how the current wave differs from previous ones, she painted a portrait of a nation on edge, where an open conflict was just a small trigger away, and has been since the Women Life Freedom movement protests began in 2022 after the death of Mahsa Amini, who was in the custody of Iran’s religious police for allegedly not wearing the hijab. “After the Women Life Freedom movement, in which hundreds of people were killed, the state continued suppressing,” she says. “Everywhere, people were talking about revenge for the past 3 years. In a way, the movement didn’t really end.

“Since the 2017 protests,” she continues, “all protests have ultimately been about regime change, but each one was triggered by a different cause,” she adds. “For most of us, the Islamic Regime is an outsider occupying our country, and in 2022, the main issue was decades of Islamic laws imposed on women, which stripped them of their rights and subjected them to violence and oppression. This time, environmental disasters, mismanagement of the Islamic Regime and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps played a role too, then the economic situation was the final trigger.”

When TWH communicated with Mitra in the very first days of the current protests, she already expressed that what was happening was nothing short of exceptional. When answering our questions some days later, she reiterated her assessment: “Previous protests were barely made of tens of thousands of people, but for the first time ever, millions came to the streets calling for regime change. Seeing millions of people ready to stand in front of gunfire was not something I could ever imagine.

“It is estimated that around 32 million came to the streets on January 8,” she continued, “and many came to the streets with their families, Gen Z with their parents!”

Still, although the protests appear to have gathered a huge number of Iranians from all walks of life, according to Mitra, a core of fervent anti-government activists helped channel popular wrath towards concrete targets and goals.

“The few people who had escaped the country following earlier protests put lots of effort on social media into training people about how they should fight back,” she says. “From what I saw, people took this advice seriously and implemented it this time: It didn’t look like a pointless gathering. Tehran was burning, fire was set to governmental buildings and police cars, and many IRGC agents were killed by protestors as well, mostly using stones or bare hands.”

Yet, in a country where the state severely curtails ownership of firearms, violence appears to have been overwhelmingly one-sided. “During the current protests,” says Mitra, “two of my friends saw these militias with heavy loads of guns marching in Tehran and speaking Arabic, but they also were present in 2022, and even 2009.”

One aspect of the current protests that Mitra is especially keen to talk about is their religious dimension. Starting in the mid 2010s, the figure of ancient Achaemenid emperor Cyrus became increasingly popular among critics and opponents of the regime. In 2016, a large gathering of revelers who had congregated on the site of Cyrus’ tomb clashed with police forces, shouting slogans hostile to the regime and in favor of the monarchy.

Protestors flying the flag of the Sassanid Empire. Picture provided by Mitra (courtesy)

In the struggle against the Islamic regime, another ancient Iranian empire has also become a potent symbol as of late: the Sassanid empire. “It began in the Woman Life Freedom movement that people took the flag of the ancient Sassanid empire to the streets,” explains Mitra. According to the legends, it is the same flag that Kaveh the blacksmith raised in his fight against the evil Zahhak. “Nowadays, you see it in every protest, even abroad.”

This bolstering of pre-Islamic Iranian history serves to create a narrative in which the current Iranian State is cast as a foreign, late, invading “other” imposing its Islamic norms upon the populace. In this context, Mitra says, some protestors have started to talk about the current revolt as the second battle of Al-Qadisiyyah, in reference to the historical battle of Al-Qadisiyyah, where, in 636, the armies of the first Islamic caliphate won a decisive battle against the Zoroastrian Sassanid empire, ultimately leading to the Islamization of the Iranian plateau.

This heightened sense of antagonism has led to more than the shouting of slogans and the hoisting of flags. Early in the protests, pictures emerged online purporting to show mosques engulfed in flames. When questioned about these, Mitra is adamant that the mosques were targeted by protestors largely due to their religious significance and ties to the state. “A lot of mosques were burnt or vandalized, I don’t know how many, but I know personally of two of them in Tehran,” she claims. “There are two reasons for it: first, people don’t feel like these buildings belong to them. They are a symbol of oppression for us. Second, these mosques (alongside those in Europe run by the Islamic Regime) are actually military bases for their propaganda, and they always use them to gather their troops and weapons for suppressing the protestors and spying on people.”

As to the ongoing repression taking place within Iran, little can be factually ascertained for the time being, as the government-mandated Internet blackout renders communication near-impossible. Where will the revolt head? And, more importantly, what do Iranians wish for their country?

For Mitra, it is extremely simple: what is needed is regime change. “For the past years,” she says, “these protests have been about taking down the Islamic Regime and having a secular government freed from Islam, and people will not accept anything less than that.”

On the topic of a hotly-debated potential American military intervention, Mitra states that it is widely supported by everyday Iranians: “Unlike Democrats who have clear ties to Mullahs and their agents in the West, Trump does not play behind our back, and most Iranians are positive about Trump and U.S. intervention,” she claims. “Iranians support this because we are already like slaves to Russia and China. We prefer having a mutually beneficial relationship with the West, especially the U.S., and also Israel, with which we had good ties before the 1979 chaos. Most Iranians would want to re-establish that connection after the fall of the regime.”

Reza Pahlavi, former crown prince of Iran, October 16, 2015. Photo by Gage Skidmore from flickr.com (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Regarding Reza Pahlavi, the exiled crown prince who has exhorted Iranians to rise up against the regime, Mitra insists that his popularity is neither artificial nor limited to exiled Iranians. During our interview, she consistently referred to him as “our leader” and stated that “even those people who participated in toppling down the Pahlavi Regime now stand behind his son as their last hope.”

When asked, towards the end of our exchange, whether she wished to clear out some misconceptions regarding Iran and the ongoing revolt, she urges onlookers in the West to consider the threat posed by Iranian State agents and networks: “Iranians do not identify the Islamic Regime as a legitimate government, but more like a mafia dominating the Middle East. In the past years, Western politicians have been shaking hands with them and letting their mafia and their families into their countries. Their agents are now everywhere from the USA to Europe, spying on Iranians abroad and doing malicious activity, especially against Jews. People abroad should treat the Islamic Regime not as a government but like any other terrorist group.”

Editorial Note: As of the publication of this article, The Wild Hunt team has not been able to contact Mitra for close to 72 hours, and her whereabouts remain unknown.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.