KUWAIT CITY – A video that surfaced on Facebook over the weekend appears to show the arrest of an Iraqi woman in Kuwait on charges of practicing witchcraft. The footage, widely shared across social media, echoes similar cases in the region and underscores broader concerns about the prosecution of alleged sorcery in the Middle East and beyond. The incident serves as a reminder for the community to remain cautious while traveling and mindful of the potential consequences of interfaith and advocacy efforts.

[Editorial Note: We reserve capitalization of Witchcraft for references to Wicca and other modern Pagan religious movements.]

In late July, Kuwaiti authorities announced the arrest of an Iraqi national, identified as Iman Abdul Karim Abboud Kazim, who is accused of practicing witchcraft, fortune-telling, and fraud. According to the Ministry of Interior’s General Department of Criminal Investigation, Kazim presented herself as a spiritual healer and lured clients by claiming she could resolve personal, financial, and family problems. She allegedly told victims she could break curses, bring good fortune, and even predict the future.

🚨

وزارة الداخلية الكويتية 🇰🇼

تقبض على ( أم السحورة ) المشعوذة إيمان عبود كاظم ( عراقية ) الجنسية وهي مقيمة في الكويت تقوم بإعمال الشعوذة والسحر والتنبؤ مقابل أموال طائلة .#الكويت pic.twitter.com/Y2BuwkSp6x

— فهد 🇰🇼 ( أخوان مريم ) 🇰🇼 (@fahadddd83) July 29, 2025

Some comments on X called for her execution, claiming it was necessary to protect the community from her ‘black magic’.

Officials said that many of her clients, often in moments of emotional or financial vulnerability, paid her significant sums in the belief that she could change the course of their lives. Investigators began monitoring Kazim after receiving intelligence reports about her activities. Following a period of surveillance, the Anti-Financial Crimes Division obtained a legal warrant and staged a sting operation in the Al-Adan district.

Kazim was arrested at her residence, where police discovered an array of ritual tools. Among the items seized were amulets, talismans, written charms, padlocks, herbal oils, and stones. Authorities said these objects were used to convince victims of her supposed supernatural powers. Both Kazim and the confiscated materials were referred to the legal system for prosecution under Kuwait’s strict anti-witchcraft statutes, which criminalize exploiting superstition for monetary gain.

The Ministry of Interior issued a public warning after the arrest, urging citizens and residents not to fall prey to individuals offering supernatural solutions to their problems. “No one should fall victim to deception cloaked in superstition,” the ministry said in a statement, emphasizing that those who exploit others under the guise of sorcery or fortune-telling will face severe penalties.

This case is not isolated. Earlier this year, in April, Kuwaiti customs officers intercepted another woman at the Kuwait-Iraq border. Officials reported that she attempted to smuggle ritual objects concealed in a false-bottomed bag. Inside, inspectors found rings and beads that she admitted were intended for use in black magic. The items were confiscated, and the woman was denied entry into the country.

Regional Patterns

Similar arrests have been reported elsewhere in the Middle East. In Sherikat, Sudan, police detained several women accused of using witchcraft to defraud people. Local reports said they were involved in a practice described as “smoking” victims—allegedly casting spells or charms in order to take their money. Authorities stated the women were acting on behalf of others and were found in possession of ritual tools believed to be tied to their practices. Sudan, like many countries in the region, has a history of prosecuting witchcraft under religious and civil law, with penalties that can be severe.

Kuwait and Sudan reflect a wider regional approach in which witchcraft and sorcery are not only stigmatized but also criminalized. In many Muslim-majority nations, laws against sihr (sorcery) are rooted in both religious doctrine and state legal systems. Authorities frequently argue that such practices exploit vulnerable people and undermine social cohesion. While enforcement varies, Saudi Arabia has carried out capital punishment in sorcery cases, and other Gulf states—including Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates—regularly prosecute individuals accused of witchcraft under fraud or superstition-related statutes.

The severity of such prosecutions stands in stark contrast to attitudes in much of Europe and North America, where witchcraft is legal and often recognized as a form of religious or spiritual practice. In those regions, Pagan, Wiccan, and other earth-based traditions are protected under religious freedom laws, though fraud statutes may still apply if practitioners solicit money under false pretenses.

Two witches meeting with a great beast in a woodcut from 1720 [public domain]

Deadly Consequences Elsewhere

[Editorial Note: The following three paragraphs contain details that some readers may find disturbing.]

Yet even in countries where witchcraft is not criminalized, accusations can carry devastating consequences. Earlier this month, the BBC reported on the brutal mob killing of five members of the Oraon family in Bihar, India. On the night of July 6, a crowd of up to 200 villagers stormed the home of 71-year-old widow Kato Oraon after a neighbor’s child died. “Accused of practicing witchcraft after a neighbor’s son died, Kato, her son Babulal, his wife Sita Devi, their son Manjit, and daughter-in-law Rani Devi were tied, beaten, and dragged to a pond before being set on fire. “

Only one teenage family member survived.

Police later identified villager Ramdev Oraon, the bereaved father, as the main suspect and arrested four individuals, including the exorcist. Authorities admitted failures in their response, as the mob violence unfolded just seven kilometers from a police station and went unreported for 11 hours. The killings left Tetgama village nearly deserted, with many residents fleeing in fear. Survivors, now under police protection, continue to grieve a crime that shattered their community.

Human rights groups say such incidents underscore how superstition and lack of education leave marginalized communities vulnerable to violence. Similar cases of witchcraft-related killings are reported annually in parts of India, sub-Saharan Africa, and Papua New Guinea, where accusations can spiral into vigilante justice.

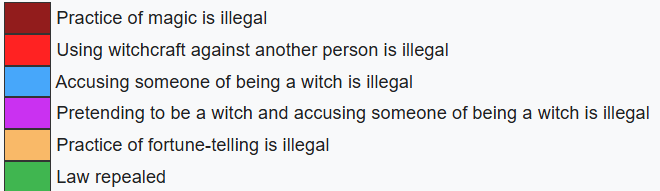

Witchcraft-related laws by country: [BorysMapping CCA-SA 4.0]

A Warning for Travelers

For Pagans, Wiccans, and practitioners of modern Witchcraft in the West, these cases serve as a reminder of the vastly different legal and cultural landscapes abroad. Ritual tools, charms, or ceremonial items regarded as sacred in one country may be treated as evidence of a crime in another. Likewise, gatherings or ceremonies that are accepted in North America or Europe may draw unwanted scrutiny or even prosecution in regions where sorcery is outlawed.

Experts advise that travelers research local laws carefully and exercise discretion when carrying ritual items. What is viewed as an expression of faith or spirituality in one jurisdiction may be interpreted elsewhere as fraud, superstition, or even a threat to public order.

The arrests in Kuwait and Sudan, the tragic killings in India, and similar reports from Africa and Oceania illustrate the continuing dangers faced by those accused of witchcraft worldwide.

They also underscore the importance of awareness for modern Pagan and Witchcraft communities, especially when traveling with ritual items or even jewelry, as well as engaging in cross-cultural interfaith activities: in a global context, the boundary between spiritual practice and criminal prosecution can be perilously thin.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.