When I was a kid, few things brought me as much excitement as going to the local newsstand to buy Donald Duck comics. In the dark recesses of the shop, that grumpy old bird was hard to miss: there were no less than four or five weekly or monthly comic magazines emblazoned with his bright orange beak or that of one his many be-feathered relatives.

Although I collected as much as I could, I always had my preference for the trade paperbacks that generally collected older American-made stories by the likes of Carl Barks and Don Rosa. The stories those two men drew always managed to hook me. They had everything: colorful characters, witty storytelling, absurdly grand stakes, and adventures in far away lands.

One day, snatching the latest copy of what must have been Donald Magazine (if my memory serves me right), I got served with just that, but on a plane my young mind could not even fathom. Donald, Scrooge, and the nephews were traveling to…Finland?

Finland? What was that?

According to the map shown in the first few pages, it was a somewhat oddly shaped country, apparently up in the north-east of Europe. I wondered for a little while if it was real. After all, old Donald comics were often filled with silly-sounding fictional countries like Brutopia (a boorish parody of the USSR), so maybe Finland was just one of those?

I quickly found out that I had been wrong on this one, and that instead of reading a purely fictional story about anthropomorphized ducks amassing wealth and learning important life lessons, I had been served with the real-life mythological lore of an actual country: the Kalevala, wherein Väinämöinen fights against the perfidious witch Louhi for control of the Sampo, a mythical magical-mechanical cornucopia, all with the helps of the Duckburg clan.

Despite being obviously made first and foremost as a piece of popular kids’ entertainment, the story was gripping, well-paced, funny, and, to me, truly exotic. (Check it out yourself here, in Finnish). With its snow-covered forested landscapes, scary sea monsters and mysterious manuscripts, Don Rosa’s story stayed with me throughout my childhood and adolescence until the day I met a half-Finnish lady who would end up becoming my wife.

A forest landscape in south-western Finland (L. Perabo)

Turns out, she also grew up with Don Rosa’s stories and as a Finn, especially loved his Kalevala homage. What she however, unlike I, she was actually familiar with the original story, having had it read to her by her father as a kid. While this discussion made me peripherally aware of the Kalevala, I was in no hurries to get to it, as I had just moved to Scandinavia and was mostly eager to delve into the region’s rich Norse heritage, something I would devote myself for the years to come.

Then, just last year, my wife and I uprooted ourselves to start a new life in the Åland islands, a semi-autonomous archipelago under Finnish suzerainty. Upon arriving there, I started searching for evidence of ancient local myths, legends, and folklore, but my quest bore few fruits.

Hungry for novel mythical experiences, and enticed by my recent review of the Silmarillion I therefore headed to the local village library, and grabbed a copy of the Kalevala (in Swedish) and a thick Swedish-language dictionary before getting to work. Little did I knew then where this would all take me.

The version of the Kalevala I chose for this mythical-literary journey was, quite evidently, a translation. Not knowing Finnish, one of the hardest European languages to learn (it features 15 grammatical cases), I chose a translation into Swedish, Finland’s other official language. The translators, a father and son duo composed of renowned Finnish poets/lyricists Lars and Mats Huldén, gave this relatively recent (1999) version a cachet of authenticity and professionalism which I thought was nice.

What left me a bit out cold with this Kalevala of mine, however, was the paucity of additional material. Besides a few lines about the genesis of the project at the beginning of the book, and a short summary on the back cover, this translation contained nothing besides the text and a chapter index. No footnotes, no endnotes, no introduction, no commentary. Just the Kalevala.

“I’m on my own with this one,” I thought, as I fearfully opened the book at page 15 and gazed at the first stanza of the first of the 50 songs comprising the Kalevala:

‘Vet du had vi borde göra ‘Do you know what we should do

vad som leker mig i hågen? what turns over in my mind?

Börja sjunga gamla sånger! Begin to sing old songs!

Låna röst åt våra runor.’ Lend voice to our runes.’

So begins the Kalevala, a call to sing ancient poems, or “runot” in Finnish. What follows, was a 380 page roller-coaster of myth, emotion, forgotten traditions, tragedy, and sorcery.

Following the incitement of the unnamed singer to his singing companion, the Kalevala begins with the birth of the world, a mystical event of epic proportion wherein Ilmatar, the divine mother, emerges from the primordial waters, before a bird lays eggs upon her emerged knee, from one of which emerges Väinämöinen.

Arguably the main character of the Kalevala, Väinämöinen is shown early on as a culture hero, establishing agriculture in his homeland of Kalevala, but also as a powerful sorcerer, challenging the young Joukahainen to a battle of spells and wits, where Väinämöinen easily triumphs. This confrontation introduces one of the fundamental cosmological orientation of the narrative of the Kalevala: the fight between the divine heroes of Kalevala and adversaries dwelling in a nebulous yet frigid and threatening North.

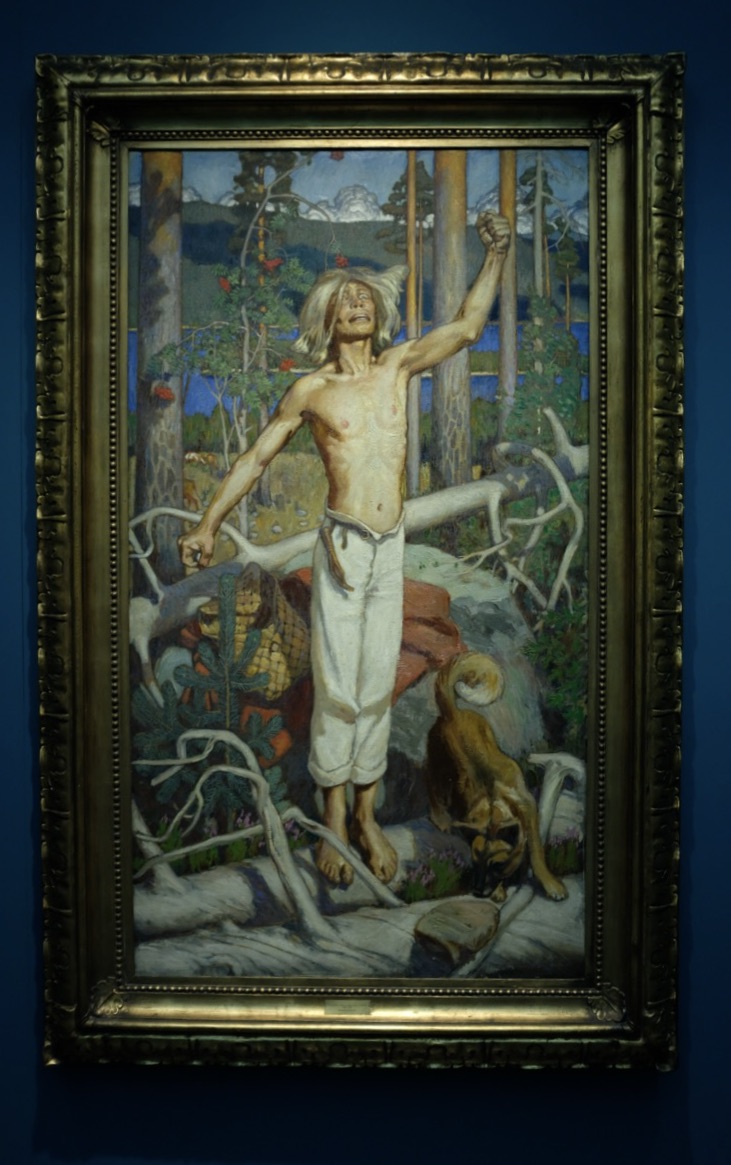

Kullervo’s curse, by Aleksi Gallen-Kallela (1899). Photographed by L. Perabo in the Ateneum museum in Helsinki (2024).

One other mainstay of the Kalevala, a feature which is throughout deeply intertwined with the heroes’ adventures into the far north, is the quest for brides. Countless times throughout the 50 songs of the Kalevala, the reader will catch Väinämöinen singing the praises of “girls with braids” or “tin-breasted maids” (as in: with jewelry, not breasts made of actual metal… although the Kalevala does indeed feature a lady made of metal at one point).

Talking about artificial contraptions, the Sampo, a magical mill which can create both grain, salt, and money, does indeed come to mind. It is one of many ingenious devices smithed by Väinämöinen’s companion, Illmarinen, in the latter’s quest to marry the bride of the North, daughter of the cunning witch Louhi. The forging, gift, theft, and lost of the Sampo, spread throughout the 50 songs of the Kalevala, constitutes a sort of loose narrative thread within the whole compendium.

Indeed, other stories found throughout the Kalevala are only tangentially related to the quest of the Sampo, but do feature recurring characters who regularly interact with the other heroes of the epic. Figures such as Lemminkäinen, a larger than life figure that will remind the Heathen reader simultaneously of Baldr and Loki, or Kullervo, a tragic hero, an orphan thirsty for revenge whose largely-independent cycle has inspired countless authors and artists in the past 200 years.

In terms of atmosphere, the Kalevala shifts almost effortlessly between a high epic repertoire of sword-brandishing warriors meeting in bloody battles, dramatic interpersonal crises between deeply unhappy loved ones, obscure accounts of arcane cosmogony, near-animistic interaction between mystical beings and shamanic-like rituals.

It is difficult to explain the breadth of narrative and aesthetics found within the Kalevala without expansively quoting from its byzantinely-structured stanzas, but suffice to say that the reader may find on one page a couple of lines explaining the proper way to clean and dry wooden spoons, only to stumble upon a hero summoning hordes of bloodthirsty forest beasts to kill his mortal enemy, just a few pages later.

Even for the most enthusiastic lover of archaic poetry, folklore, and myth, the Kalevala might prove a tough nut to crack. It certainly was so for me. Although I thoroughly enjoyed my reading journey throughout (maybe the lengthy household upkeep section notwithstanding), the opacity of some aspects of the plot, as well as the at time obscure internal logic of the epic made me stop more than one to recollect my thoughts. This is when I started looking deeper into what this book I had in my hands actually was, and how it came to be, and that story proved nearly as fascinating as the tales contained therein.

The Kalevala, rather than being a singular piece of literature, actually came to be in slow, gradual increments under the aegis of Finnish medical doctor and folklorist Elias Lönnrot. Lönnrot, who came of age in the early days of Finland’s conquest by Russia, studied medicine at the university of Åbo/Turku. There, he encountered the works of Finnish scholars and poets who, since the 17th century, had been uncovering bits and pieces of Finland’s ancient myths and legend.

After graduating, Lönnrot, following the advice of fellow physician and folklore enthusiast Zacahrias Topelius the Elder, relocated to eastern Finland, in the vicinity of Karelia, a heavily forested rural region whose largely illiterate population still sung ancient songs that had for the most part fallen out of fashion in the western parts of Finland.

Elias Löönrot (public domain)

Over the next couple of years, Lönnrot would organize a dozen trips throughout the wilds of eastern Fenno-Scandinavia. From the arctic coast of the White Sea to the cities of Estonia and the isolated fisher-farmers communities of innermost Karelia, the young doctor, who still had to reckon with making a living through his medical practice, accumulated more ancient poetry than just about every single scholars before him had done combined.

Finding troves after troves of elderly singers who could, in the blink of an eye, recite poems hundreds of lines long, Lönnrot got the idea to assemble some of those in thematic entities, cycles that could together form the core of a book, a book which would showcase a tradition very few knew about.

That book, however, not yet named Kalevala, would go through many iterations. Two drafts were written, but never published, before a first version was published in 1835. That first actual edition was then superseded by a much larger Kalevala, published in 1849 and gathering material from a much larger geographical area that its predecessor. Then, in 1862, Lönnrot published yet another version of his magnum opus, a school-oriented compact version not even half as long as its 1849 predecessor.

The Kalevala can therefore be seen just as much as a project than a product: a fluid, dynamic entity arisen from an ancient, yet living tradition, recontextualized over and over again by both singers, folk collectors, and editors, the foremost of which, Elias Lönnrot being at the end of the day but a cogwheel in a much larger mythopoetical machinery.

Yet it is important not to downplay the innovative part Lönnrot had in, if not straight up writing the Kalevala, at least defining it and bring much of it to light. While the vast majority of the stanzas found in the Lönnrot’s Kalevala were taken straight out of the mouth of traditional singers with little significant emendations, the way he organized the massive amount of source material at his disposition was very much deliberate.

Inspired by Romantic poets, philologists, and folklorists, especially the Germans Johann Gottfried Herder, Friedrich August Wolf, and the Brothers Grimm, Lönnrot was originally of the mind that there once was a great epic of the Finnish people and that his job was just to reconstruct it back from its late, somewhat corrupt stage, into its archaic stage.

In that time, it was also common for folklorists and philologists to advance that epic folk songs were different from learned, classically inspired poetry and that instead of being the work of individual poets, they simply emerged, almost miraculously, out of the very spirit of nations.

In the early stages of his work, Lönnrot was thus after a grand epic embodying the spirit of the Finns, and aimed to restore that ancient knowledge to its former glory. Over time, however, and as he gained an increasingly greater command of the poetic language and the narrative substance of the poetry he sought, Lönnrot began to comprehend the subtle yet significant ways in which poets would alter and recast their subject matter and how variants of the same stories could be related.

This growing awareness of the intricate workings of folk material translated, for the first version of the Kalevala, into the addition a number of variant poems collated at the end of the book. By the time Lönnrot was working on the publication of the second version of his epic, however, he had adopted a different mindset. He had started seeing similarities between the way oral folk singers would utilize and reshape old poems and the way he himself collected, edited, and transmitted said poems.

By the time of the publication of the second Kalevala in 1849, the physician turned folklorist had made his choice: he could not simply just defer to the authority of tradition. To weave the disparate stories of the old Gods and heroes into something greater than just the sum of its parts, he had to take upon the mantle of both the tradition bearer and the creative innovator.

The cover of the first volume of Elias Lönnrot’s 1835 Kalevala (public domain)

Commenting on the arduousness of the task, and the gargantuan amount of sources he had at his disposal, Lönnrot famously wrote: “Now the collected poems could well yield seven Kalevalas, each entirely different.” Yet in the end, Elias Lönnrot, the folklorist, the traveler, the physician, the student, the ethnologist, the editor, and finally yes indeed, the rune singer did birth one longer Kalevala, one which was just as indebted to his creative process and his inspiration than it was to the old songs and ancient lore it was forged out of.

Although the 1835 Kalevala had made waves in the Finnish and greater European intellectual circles, only 500 copies were originally printed, which took 12 years to sell out. The 1849 version, on the other hand, quickly became an object of popular affection domestically, and the subject of much fascination everywhere else. Numerous translations of it, aimed at a more general public, regularly came out throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, quickly making it the most translated work of Finnish literature in history.

At home, too, the Kalevala kept making waves and influencing the destiny of the still constrained young nation. Its very existence gave the Finnish language a status it never had until then, and several linguistic innovations introduced by Lönnrot entered common usage. His well-documented poetry collecting activity was also very much ahead of its times and played a key role in establishing modern folkloristics.

Truly, in collecting, shaping, and advocating for the ancient legends of Finnish gods and heroes, Elias Lönnrot managed to strike a nerve, and become a source of near contagious inspiration. No wonders, then, that J.R.R. Tolkien’s very first literary love affair was with the Kalevala, and that the Finnish epic played such a pivotal role in the development of his legendarium.

As I wrote in my review of the Silmarillion, the relationship between J.R.R. Tolkien and the Kalevala extended further than the mere inspiration the former got from the latter. After his death, Tolkien left such a humongous amount of notes, manuscripts, drafts, and other writings that his son Christopher essentially had to patch up and shape his late father’s mythical stories in much the same way that Lönnrot did with the Kalevala, albeit working from written in lieu of oral sources.

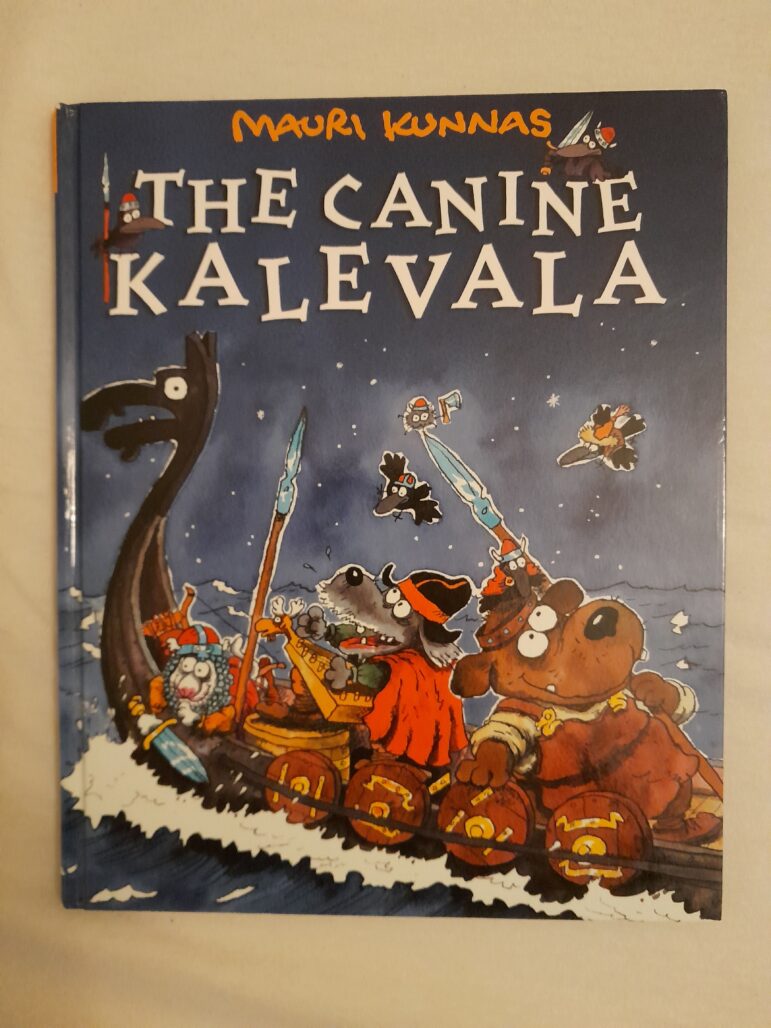

Beyond Tolkien, Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala inspired so many other authors, poets, and artists that even providing but a concise overview would deserve an article of its own. If I were to name only a single work, however, it would be Mauri Kunnas’s Canine Kalevala, a charming, kids-friendly retelling of the Kalevala which utterly fascinated my four year old, and which incidentally was one source of inspiration for Don Rosa’s own retelling.

There truly is something magical in the tales of the Kalevala, something which seems to inhabit those exposed to it. Maybe it is the echo of the first songs composed about the gods and heroes of the ancestors of the Finnish people, more than a millennium ago, still resounding, regardless of the shape they take, the spaces they inhabit and the people who are listening to it? At this point, I feel like I both said both too little and too much about this unique work of literature, folklore and myth and I am left with just one last statement to make: give it a read, you will never forget the journey you will make, and who knows, maybe you too will be touched by the echo of rune singers of ages past, and bring the tradition to grand, novel horizons?

Mauri Kunnas’ the Canine Kalevala (English translation of the second edition, 1999)

Addendum

I lied when I said that I would only mention one more work of art inspired by the Kalevala. I need at the very least to mention the music of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, just as much a titan in the world of classical music as Elias Lönnrot was in that of folklore and myth. Sibelius was a highly productive individual, with hundreds of pieces under his name, and many of his most famous compositions directly reference and were strongly influenced by the Kalevala. His most excellent music acted as a fitting soundtrack to my reading of the Kalevala and the subsequent research and writing it lead to (as I write those lines, I am halfway through Karajan’s rendition of his fourth symphony).

As a gift for the few who managed to read through the previous 3,000 or so words making up this article, I thought I would provide a playlist of what I think are Sibelius’s greatest compositions, a perfect aid for delving deep into the Kalevala or working through whichever backlog of tasks each and every one of us get swamped with sometimes. Although I would truly recommend listening through Sibelius’ entire œuvre, as I did, the following selection should give you a good idea of his artistry and hopefully inspire you (that word again!) to research his work further.

Addendum II: Bibliography

While I am at it, I thought that I could just as well provide readers with some of the resources I employed in the research and writing of this article. As with the article itself, this only represents a very superficial and admittedly subjective pool of sources but in the hands of an inquisitive soul, these will already do wonders.

Martti Haavio’s monograph on Väinämöinen (English translation, second edition)

- The Five Performances of the Kalevala : A great all around introduction to the process of collection and creation of the Kalevala, covering numerous key aspects of this complex topic in a clear and concise prose written by one of the most celebrated scholars in the field.

- Väinämöinen, Eternal Sage: One of the few book-length commentaries on Kalevala poetry and mythology available in English. Originally written in Finnish by professor Martti Haavio, this book, although using a rather antiquated language, gives a good overview of the shaping of key narrative sections of the Kalevala without focusing too much on Lönnrot’s own work.

- The Kalevala society: established in 1911, the Kalevala society is the oldest scientific research organization dedicated to furthering the study of and communicating the Kalevala. The society’s website is a great pedagogical resource for people curious about various aspect of this imposing work.

- Kalevala Around the World: a project spearheaded by the Kalevala society, Kalevala around the world is a resource detailing the various translations of the Kalevala, from its earlier days until the twenty-twenties. This bilingual (English and Finnish) database gathers a treasure trove of information related to the translation, the reception, and the influence of the Kalevala around the world.

- Juminkeko: located in east-central Finland, not too far from Elias Lönnrot’s beloved Kajaani, Juminkeko is a culture center and museum dedicated to the Kalevala and Karelian culture. Although I cannot personally vouch for its facilities (yet), its website provides an enormous amount of resources related to the history of the Kalevala and the works of Elias Lönnrot, all for free and readily available in no less than four languages (Finnish, Russian, English, and, surprisingly enough, Italian!)

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.