Editor’s note: This essay discusses sexual assault and the rape culture that permeates both “Rosemary’s Baby” and the society that created and views it.

What is a coven?

Looking at where the word comes from, we start with convenire, a verb meaning “to come together.” I bet your coven comes together. From that same word, we get “convent,” where nuns come together, and “convention,” for where nerds come together. This is among our first instincts and desires; we seek out our people as babe seeks mother. In families and clans and villages we come together. In America, this is our first explicit right: to come together and “peaceably assemble.” It comes together in the same covenant where we keep our freedom of religion.

When a woman comes together with the devil, we get “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), based on Ira Levin’s 1967 novel of the same name.

John Cassavetes and Mia Farrow as Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) [Paramount]

Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and Guy Woodhouse (John Cassavetes) find a frankly gorgeous Renaissance revival apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and rent it despite his being an out-of-work actor and her not working at all. When banks and lending entities come together, we get credit scores, but the Woodhouses escape all that by decades. They decide (when Guy gets one role in one play – and only after his rival for the part is mysteriously struck blind) that it’s time to have a child. When a man and a woman come together, they sometimes conceive.

And then an eccentric old couple from upstairs introduces themselves as Minnie and Roman Castavet (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer) and act a little weird. When they come together with their neighbors and offer them chocolate mousse that has a “chalky undertaste,” the audience knows Rosemary is in trouble. So does she. But she’s not allowed to say so.

Most of the horror in this film comes together out of our expectations of a loving married heterosexual couple who have decided to have a child. We expect that they will conceive tenderly, but Rosemary awakens to discover scratches all over her body and evidence of a sexual assault of which she has no memory. Undeterred by her distress or her dreams of a monster with yellow eyes, Guy tells her he didn’t “want to miss baby night,” and simply raped her while she was unconscious.

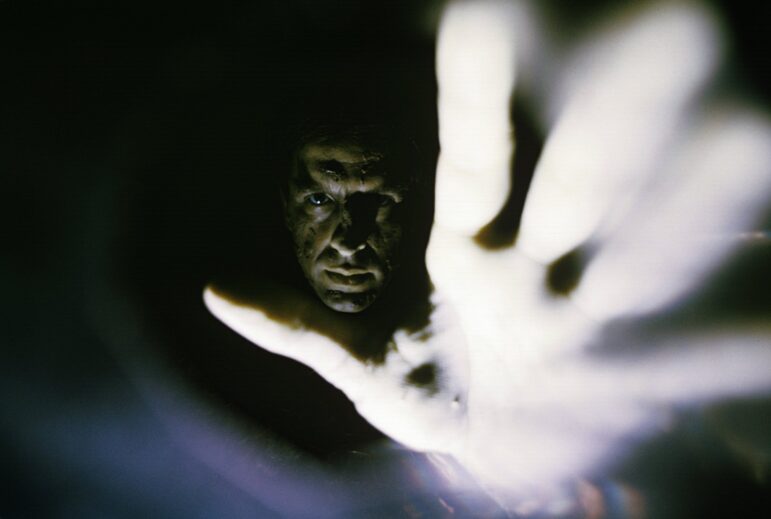

John Cassavetes as Guy Woodhouse in “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) [Paramount]

Instead of gaining weight and glowing, Rosemary becomes thin and gaunt as she gestates the result of that night. Instead of coming together in joint expectation of joy, Guy distances himself from his wife, enjoying continued acting success and being seduced by Hollywood. Instead of coming together with the imagined and felt child in her womb, Rosemary dreams she has sinned against the church of her upbringing.

The movie comes together tense and tight, seamlessly sealing dream and reality, bringing the impossible schlock idea that underpins the witch trials in the American historical imagination (“I saw Goodwife Woodhouse cavorting with the devil!”) into a modern and realistic setting. It won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay (then called Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium) and performed critically at a level to which most horror films dare not aspire. Critics at the time said the film felt “almost too plausible,” expressing frustration that nobody in the movie catches on fast enough.

What is there to catch on to? A friend slips Rosemary a book on witchcraft and she figures out that the Castavets are part of a coven. Here’s where things might not come together for the modern Pagan: the culture that produced, enjoyed, and made a massive hit of this film did not meaningfully separate Satanists from witches. A coven is a coven is a coven, and most films of the mid-century use that word to mean “those who come together to worship Satan,” as well as “those who come together to cast spells,” and “those who come together with their fellow vampires.” The idea that a witch, a member of a coven, is a person in league with the devil is a much older one than our community’s current definition of it. When I rewatch something like Rosemary’s Baby, I always come away with the impression that we shouldn’t take such pains to argue the finer definitions of the term. We should treat the difference as irrelevant, and refuse to explain ourselves. The truth is messier than we can politely declaim.

Messier still is the subject of the director of this film. When a rich and powerful man of 34 comes together with a girl of 13 to imprison and rape her, it’s a crime in almost any country. When he defends himself by saying, “everyone wants to fuck young girls,” we come together and allow him to escape punishment of any kind, because we do not recognize the humanity of girls or women in almost any country.

When we come together to watch a movie made by a rapist about a woman who is raped, who is not believed, who is treated as an object; when we note that no one in the film is punished in any way for this crime; when we see them lie and tell her that her child was stillborn and then let her listen to him cry from a nearby apartment – we are in a coven. Not coming together to watch movies made by rapists does not get you out of this coven. This coven has members on the Supreme Court and in the papal conclave, coaching gymnastics and quietly living in the same apartment building as you. It’s a coven of witches and rapists and artists and Satanists and misogynists, and the cauldron we stir is big and hot and everybody has to drink from it. There is no option to pass, or to walk away.

In the end, Rosemary comes together with the coven. Her breastmilk has been consistently taken from her, and she trusts her instinct that it’s being fed to her son. She discovers Adrian, as the Antichrist has been named, and goes through visible shock, disgust, wonder, pity, grief. Finally, she chooses to sit beside him, rock his cradle, and sing to him. She has the option to pass, or to walk away. Instead, mother and child come together.

Mia Farrow as Rosemary Woodhouse in “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) [Paramount]

Mia Farrow, a star at 22, was served divorce papers on the set of Rosemary’s Baby. Her then-husband (and probable father of her eldest son) Frank Sinatra did not want to come together with her anymore. Convinced by the director not to leave production under the strain because she was guaranteed an Academy Award nomination, Farrow chose to come together with cast and crew and finish the film. Farrow was not nominated.

When we come together to rewatch this film and admit its genius, admit its primacy among the greatest of horror films a half-century later, we come together with all of this. As Pagans, we come together with a lot of things we don’t recognize as our coven, many things we don’t want to be part of or associated with. Like Rosemary, we don’t get to choose our neighbors. We don’t even get to choose whose children we carry. Each of us must choose whether we’re going to sing to and nurture this rape-begotten world in its cradle and maybe teach it some kindness despite its terrible destiny, or choose ourselves and walk away.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.