“I do have a strong suspicion at this point that everyone who attends a book festival… is already sold on the power of storytelling,” Daniel Lavery wrote in a recent article. “The same is almost certainly true for the power of the imagination, and the power of words (or ‘the written word’ if you’re really laying it on thick). Therefore we can take it as a given that everyone is on the same page when it comes to storytelling, imagination, and words, and it is no longer necessary to invoke those powers.”

In the context of his article, he is talking about emotional power, not magic, but as I read it I knew the context was different, for me. It is not exactly shocking, in the magical community, to suggest that words have power. Taking a page from Patrick Dunn, I have always thought of magic as the language that we use to speak to the universe. Often that’s quite literal – many Witches use words of power, chanting, and sigils to communicate their intention in their spellwork. That is practical magic, intended to use language to work their will. I don’t know of nearly as many practices that lean on the practical, magical power of storytelling.

It’s a concept I’ve been playing with for a while in my practice and my theology, pondering the ways in which inspiration, repetition, and collaboration inform my magic and my writing. I have joked, in tones that are less and less joking, that storytelling is the paradigm I use for my magic more than any other. If magic is the language we use to talk to the universe, stories are how humans talk to each other, create shared meaning, intentionally change minds and circumstances. I have heard people talk about telling a story as a magical act, but I know fewer people who practice magic who are ready to sit down and ponder on the magical implications of the ways they retell their myths, the fanfiction that they write, or the way they approach creative writing in general.

One author who gestures toward this is Ada Palmer. At the end of her Terra Ignota series, Palmer’s acknowledgements meditate on fictional characters and “:..the fantastic limbo where they do dwell, not dead or living, our companions of imagination, populous as we who breathe. It isn’t real the way a place – Paris – is real, but real like language, melodies, or smiles (we invented smiles), which are material phenomena – atoms moving, neurons firing – real things, just made of us.” She talks about them existing in the same way that the past exists, and goes on to say that “…we all have asymmetrical relationships with people far away, in space, in time, across the barrier between our real world and the shadow world which contains both our past and [Sherlock Holmes]. Worlds which are not real (past or imaginary) can still teach us, warn us, just as friends who are not with us can inspire us.”

Reading that for the first time gave me a shock of recognition. After all, I know Sherlock Holmes. Talking to him using the same tools that I would use to talk to a god or an ancestor was one of the events that shook my understanding of stories. Thinking about him as existing in a place – a place as real as Olympus and Constantinople – offered a whole new paradigm for how my spirituality works. It offered more weight to the metaphor of maintaining my spirit relationships as long distance relationships, which was nice – but it begged a lot of questions at the same time.

I come out of fandom, where one of the most loving things someone can do is to engage with the text, write another version, put a favorite character through (often terrible) situations. When my often-too-literal brain seized on the idea of characters as being real, in some way, the philosophical spiral about free will, and my responsibilities as a writer, dragged me into a dark place. If I told a story about violence, was I doing real harm? If I wrote a story with characters who were bad people, was I bringing more of their energy into the world? If I told a story that already existed and changed something, was I forcing change onto people who did not want it?

The questions froze me in my tracks. My writing dried up and with it, my spiritual practice. I didn’t know how to write a ritual without telling a story. Now, I wasn’t sure I knew how to tell a story without writing a ritual. Every creative idea I had died, crushed by the weight of interpretation and theory. For the first time in my life, I could not write my way through my challenges or use my stories to process my grief. I could not bear to call my friends in that real/unreal shadow realm where they lived. The world got a lot smaller.

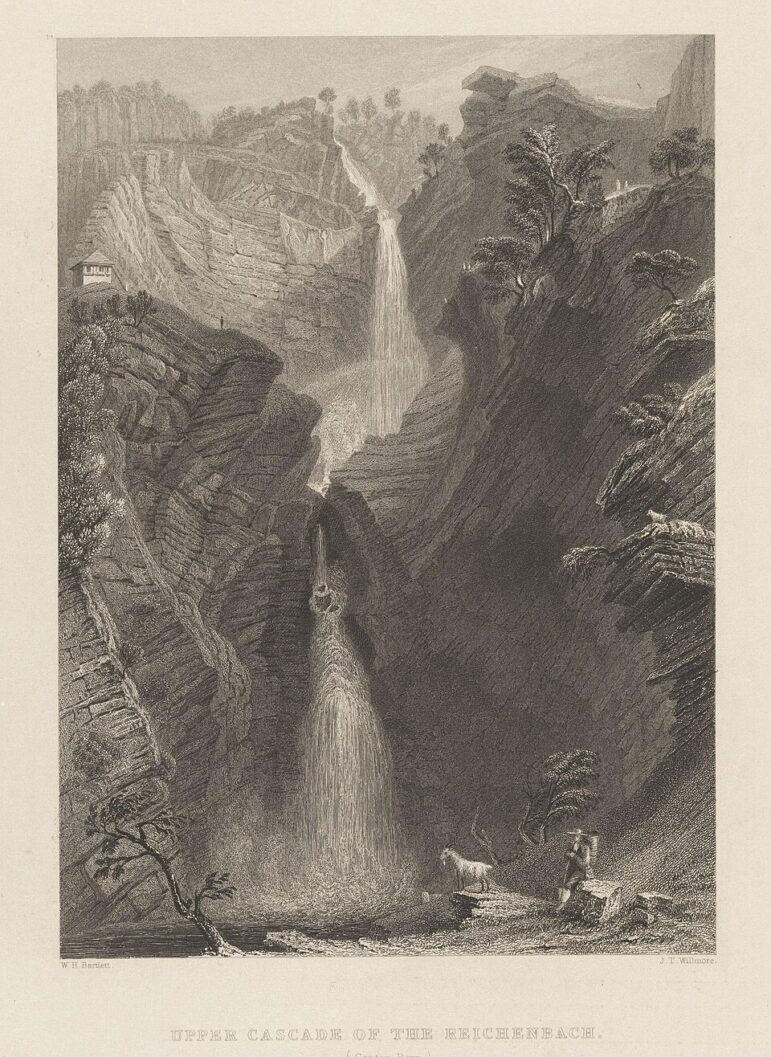

Print by James Tibbits Willmore after William Henry Bartlett, Upper Cascade of the Reichenbach (Canton Bern), engraving, London, 1836.

The god on the stage is dressed in a silver suit. That hasn’t changed in any of the productions I’ve seen. Everything else changes – age, race, gender, stature – but the suit stays the same even when the shirt beneath it dissolves into lace or rolls up its sleeves to show the wearer is off duty, hanging out with family. “It’s an old song,” the god croons, welcoming us in. “It’s a sad tale – it’s a tragedy. It’s a sad song. We’re gonna sing it anyway.” Behind the god, a trombonist crows one of the opening airs, and the cast of Hadestown introduces the major players, the basic structure of the story they’re about to tell.

Every time I have seen Hadestown there has been someone in the audience who does not know the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice that drives the plot of the musical. The opening song is an introduction of the major players and a warning – this does not end well. By the end, there is always someone who has forgotten that warning while they were caught up in the tale, someone who breaks into tears in the quiet theater during the inevitable end.

“It’s a sad song,” Hermes reminds the audience, breaking the silence as the closing number begins. “But we sing it anyway. ‘Cause here’s the thing – to know how it ends and still begin to sing it again as if it might turn out this time.” Around Hermes, two hours after the curtain rises, the stage resets to look just as it did in the opening number. The story begins again, recursive, but slightly altered in the details. Maybe next time, the musical suggests, it will be different. Every time someone tells the story, it carries the hope of a better ending. It reminds us that better endings are possible.

After the musical, I am always the same, turning to my companion with tear-bright eyes. “It’s the best ritual I’ve ever seen,” I say, fervent and delighted. “They’ve got to know – they’ve got to know! They close with an offering!” This is usually said as I clutch my own drink, bought so that I can participate in the two toasts that the play offers up. My companion is never as convinced as I am, but is usually game to hear me out as I fly high on the details of the staging, the audience’s reactions, the specificity that this cast adds in their reading of the text.

I leave the theater turning over the themes of the story, the hope baked in – that love will prevail, that we will face down depression and isolation and manage to keep our heads up those extra three steps we need to leave the shadows, that workers will realize they outnumber those who keep them oppressed. Maybe this time something will change. It’s a powerful spell.

Orpheus and Eurydice by Alessandro Varotari [Gallerie Accademia]

There is only one way that story ends. Even a reimagining like Kaos agrees on that. If Orpheus is brave beyond his last step and keeps his eyes forward, he is no longer Orpheus. His story becomes something else – a response to the original, perhaps, but no longer the same myth. His story is defined by his failure. Orpheus turns around. That’s always true. But his story, tragic, flawed, unabsolved, has been told for millennia. There is a reason to tell it.

In the end, that’s what pulled me back to writing. The theory of it – what my role was, how much power I had – started to matter less. Besides, I have had no more luck telling the characters I write what to do than telling the friends who live down the street how to feel. When I try to do either, something important breaks in the relationship. I am reminded of Schmendrick, poleaxed by magic and letting it work through him to summon up the fictional Robin Hood. To cast a successful spell, at least in the beginning of his journey, he had to let the story tell itself.

So I am letting myself tell tragedies, again, when the story calls for it. I am calling my friends in that shadow land and asking how they’ve been, what sort of struggles they’ve been handling, how they’ve coped. I am letting old stories retell themselves, seeking a new resolution, and I am imagining new stories that talk about pain and failure and the possibility of success. I am trying to open myself up and let the magic do what it wants.

On good days, when the words come easily, I wonder if perhaps stories are one of the ways the world talks back to us. Perhaps storytelling is always, and necessarily, an act of collaboration with far off friends. Every time I tell a story, I add something of my voice, my stance, my understanding. Every time, the story is something new.

What is that, if not magic?

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.