“It seemed that the land would be torn by war, and saved by miracle alone.”

Disney films like 1963’s The Sword in the Stone commonly begin with a storyteller reading from a book, richly illustrated by the animators to introduce the aesthetic, character design, and vibes of the movie to follow. But Sword opens first with a minstrel singing the setup: the miracle of the sword in the stone, meant to save Britain from the darkness of an age of leaderless chaos. Like most children who watched this movie on VHS while parked on a patch of shag carpet, I didn’t realize the first few dozen times I saw it that the word “miracle” here existed absent any Christian context. The miracles given to the young King Arthur of this tale are the miracles of Welsh paganism, and the sword is the last and least of them.

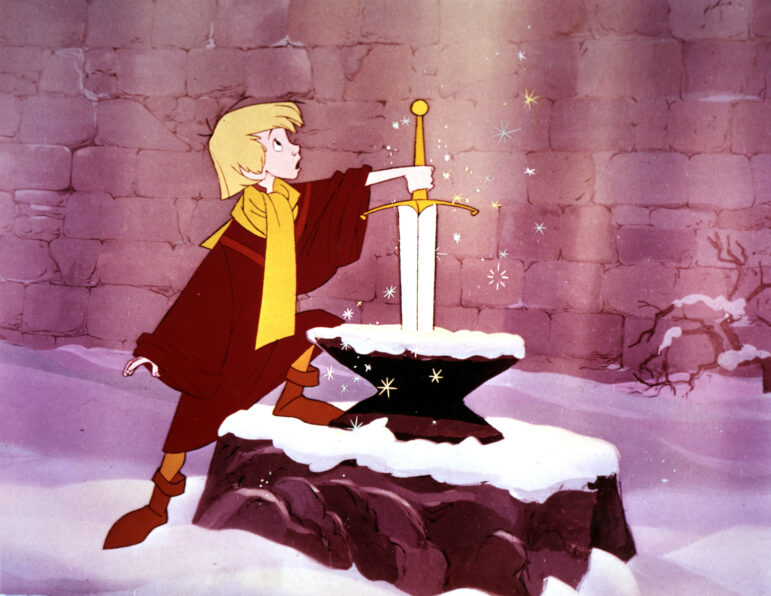

Lobby card for The Sword in the Stone (1963) [Disney]

Based loosely on T.H. White’s 1958 The Once and Future King (which was itself based on Thomas Malory’s 1485 Le morte d’Artur), Sword takes its place in the rich and ongoing Arthurian legend that’s grown to encompass everything from its 1967 medieval revival counterpart Camelot to my personal campy favorite, King Arthur and the Knights of Justice, a ‘90s cartoon where a high school football team fall through a crack in time and land in ye olde England.

This story often involves the transitional years between Roman Britain and Christianized Britain, around the year 500-600 of the common era. This is partly because a 12th century Latin Historia Brittonum records a king (or tribal war-chief) named Arthur, with a son named Mordred, both of whom died at the Battle of Badon in 518. That person may be the historical Arthur, or there may have been no such person. What we have of him now, what Disney made their movie about, mostly comes from Welsh myth.

Us rugrat kids loved seeing Merlin turn young Arthur (called “Wart” by his foster-family) into a fish, a bird, and a squirrel to sing him little songs about the nature of existence and teach him the meaning of life.

It was decades later that I encountered the story of Taliesin, in the collection of Welsh folktales called The Mabinogion. In these stories, I read of the goddess-witch Ceridwen, who brewed a special potion in her cauldron to give her son incredible gifts of wisdom, far-seeing, cleverness, and long life. She sets a young servant to stir it for her, and when a bubble on its surface pops and burns him, he puts his injured finger into his mouth and his eyes open wide. Taliesin now knows everything, including the terrible understanding that you can never un-learn what you know, and that his mistress was going to be royally pissed by this outcome.

What follows is a shape-shifting chase: Taliesin becomes a hare and Ceridwen becomes a greyhound to run him down. He becomes a fish and she becomes an otter. Finally, he becomes a single grain and hides among the others strewn upon the earth, and Ceridwen becomes a chicken, eating them all up. Once swallowed, Taliesin grows inside her, becoming her son after all, if not the correct one to receive the gift. What can we say, except that magic always works?

I remember putting those stories together: becoming a fish and a bird, Merlin the wise and far-seeing as the grown-up Taliesin, Arthur taking on all this new knowledge that was perhaps never meant for him. I love the way these stories swallow and become one another: Merlin teaches Arthur how to be an animal, how to see in a new way, and Arthur fulfills his destiny, and the story keeps getting told. Merlin duels Madam Mim (Madam Morgana, perhaps?) at the end of Sword, becoming not her child but a germ that lives inside her body and makes her sick. One thing becomes another, in the mother, in the mother.

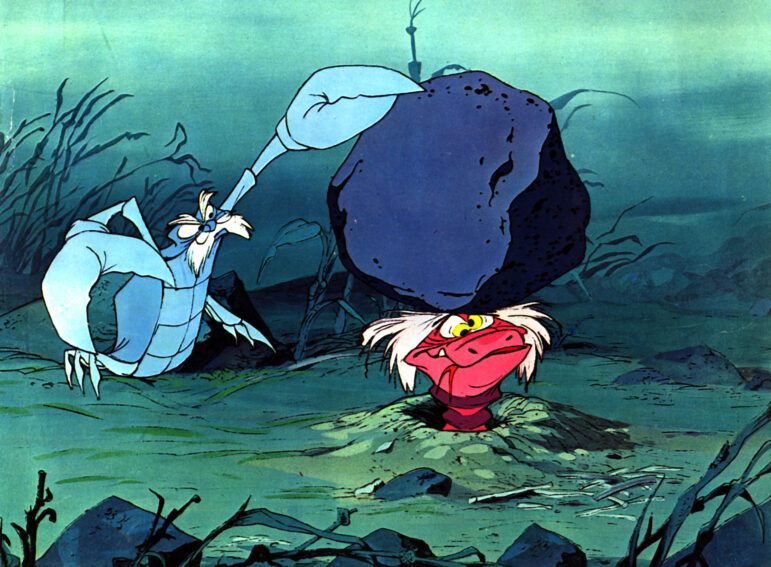

Merlin and Mim’s shapechanging duel in The Sword in the Stone (1963) [Disney]

We kids who were raised by movies and TV got turned loose on the internet as puberty hit, and the very first thing I looked for was more witchcraft. My first exposure to the Song of Taliesin was through a dubious translation that nonetheless blew my mind. It still exists, as an artifact of Web 1.0, and I have no idea who was responsible for it.

This page told me what I was looking for, in the undercurrent of stories like Stone, by naming the Book of Pheryllt. In its final lines it introduced to me the concept of the distressed protagonist: is the story about Arthur, or Gwion, or Anwnn, or Taliesin? At the time I was up to my eyeballs in Joseph Campbell, and I was experiencing the dawn of premature enlightenment. All heroes might be one hero. All gods might be one god. The internet was just another faceted seeing stone through which I might glimpse the ever-changing kaleidoscope of the divine.

That period between Roman rule and the inexorable rise of Christianity is also the setting of some modern retellings of this endlessly retellable tale, bringing historical British Paganism into the story, as well. Authors like Natania Barron, Jack Whyte, Edison Marshall, and (yikes but it has to be said) Marion Zimmer Bradley focused their stories on the tension between a still-Pagan Britain and the rising tide of missionary Christianity in the isles at that time. (For more on this, see Ronald Hutton’s The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy, 1993).

This is by no means foregrounded in Sword, but I find it curiously present. From the miracle of Arthur pulling the sword from the stone, to the light cast upon him in the moment in the churchyard in which the stone stands: without any cross, any marking, or any indication of Christianity in the low animated skyline of medieval London. Grumpy and cheerless Archimedes the owl, Merlin’s boon companion, named in homage to another great Pagan, refers to England as being part of “Christendom” in a single throw-away line, but that is all. Without the intrusion of Christianity, we have the opportunity for a kid’s movie that showcases some Pagan ideas from an ancient Pagan source.

Arthur and Excalibur from The Sword in the Stone (1963) [Disney

The sword that Arthur pulls is another shape-shifter. The legendary Excalibur is introduced to the myth by Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his 12th century Historia Regum Britanniae, another pseudo-history that wraps together Pagan Britain, Christianity, Welsh myth, and other things into the sword of destiny. It’s the sword that Arthur pulls, but it’s copied by Merlin, wielded by Lancelot and Galahad, ransomed by the Lady of the Lake, and fits into a magic scabbard made (and sometimes stolen) by Morgana le Faye. The legend is always changing from one thing to another, being gobbled up and sweated out, being birthed into new life with new names, being boiled up in the cauldron of Ceridwen to become what it must be next.

I’d like to hope that fewer kids are raised nowadays by a box of VHS tapes (or a streaming service on auto-play), but I find myself hoping that witchlets of all ages will break into the vault for this Disney classic. I hope they learn to be fish and birds and squirrels, but also wise magicians when the time comes for them to teach the next generation of Warts. My fervent wish is for them to have access to good translations of ancient wisdom, but also playful and accessible texts like Merlin bewitching his household tasks with jazzy musical numbers.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.