Editor’s note: This film and review mention sexual violence.

Folk horror is the richest vein of Pagan cinema, bleeding lurid and strange blood despite how narrow it is. When looking for more films that carry the weird and the wonder of witchcraft, most seekers will encounter the “unholy trinity” of films that established the aesthetic of folk horror in British movies: “Witchfinder General” (1968) and “The Wicker Man” (1973). Smack in the middle of those two, the seeker will find the 1971 folk horror unsettler supreme: “The Blood on Satan’s Claw.”

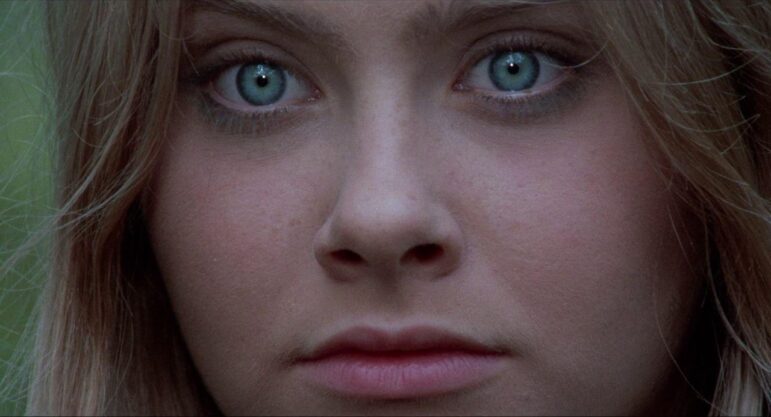

A still from The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), a close-up of Linda Hayden as Angel Blake [Tigon]

The aesthetic in question is often characterized by costuming that evokes both the flowers and free-love of the 1970s in England, which was in the midst of a medieval revival. The result is a sexy renaissance faire where the old gods are the objects of both veneration fascination, usually resulting in murder. “The Blood on Satan’s Claw” goes a little farther than a simple sacrifice. It draws out the mystery of the unruly body, and grabs a hold of the third rail of ritual sexual violence. Thus the aesthetic is electrified, the censors are baited, and the question of the body is lit up with the lightning.

We open on a peasant plowing the furrow of dark, fertile earth. This is sort of a metaphor. A strange corpse with human and animal characteristics is turned up in this field, and reported to the local magistrate. Meanwhile, a young potential breeding pair is scheming to get married: Peter and Rosalind. But madness befalls Rosalind, followed by illness. What could be causing the downfall of a hot young blonde?

Why, it could only be witchcraft.

Right away, the sexualized body is an endangered body in this film. The desexualized characters – the older folks, the servants, and the clergy – are all exempted from the violence and the evidence of sin. The evidence, in this film, is more obvious than most. Whereas strange behavior often characterizes the witch or the person in league with Satan in many of these films, the afflicted/enspelled of “Claw” start to grow fur on their bodies. As the film builds tension through childish games of “vanish” or hide and go seek, it also builds the secrecy and suspicion of puberty and sexual development. After all, what body grows fur? It is the body of an animal, a being without reason or restraint. Or it is the body of a teenager going through puberty, newly nubile and just as devoid of reason and restraint.

A still from “The Blood on Satan’s Claw” (1971), showing the witchmarked fur on the back of one of the film’s nubile youth [Tigon]

The image of the adolescent body, especially the body when coded as female, is commonly associated with witchcraft and possession narratives alike, from Regan MacNeil in “The Exorcist” (1973), 12 years old and right on the precipice of being possessed by that terrifying demon known as womanhood, to Thomasin, the witch who writes her name in the devil’s book in 2016’s “The Witch.” Puberty causes the body to become restless, no longer innocent, capable of reproduction and thus rebellion against codes of sexual behavior, and to grow fur in embarrassing places. It renders the sexless child into something bestial that cannot be easily controlled. In “Claw,” it renders the children into orgiastic and animalistic monsters. With wispy mustaches and the faintest of pubes, these children grasp the power of sex and Satan and become “witches” of a very predictable sort.

“Witchcraft is dead and discredited,” says the most educated and citified member of the ensemble, his wig all in curls and his pearls all a-clutch. “Are you bent on reviving forgotten horrors?” “Claw” is set in a period in England after the last state executions for witchcraft (1682) or, according to Phyllis J. Guskin, the last trial for the same (1712), but during a time when those events would still have been in living memory. This span of time sets up a false sense of eradication or security, wherein most people might believe that witchcraft is no longer a threat to decent people or Christian society. However, like the dormancy period of the pituitary gland, witchcraft simply springs anew when the time is right. When Angel, another pubescent blonde, attempts to seduce the curate in “Claw,” she does so by simply showing herself to him: the secret spring is sprung and her fur is grown in the full 1970s fashion.

The last innocent among the girls, and the only brunette, Cathy, is the subject of predation at the film’s climax. Tied up and kidnapped by a pair of her classmates, she’s garlanded with flowers and led to a place of ritual in the uncivilized woods. The teens process and hum and chant together, suddenly solemnizing their play. They show us that the business of children becomes deadly serious when their fur is grown and sex enters the scene. The late bloomer is sacrificed to Behemoth as the youths chant an offering of flesh and skin and the inevitable truth is revealed: Cathy, too, has grown a patch of fur. It is the way of all things. A boy from the company rapes Cathy while the onlookers beat the pair with blooming branches, after which Cathy is murdered. The scene is unctuously filmed, with close-ups of the onlookers rapt with lust, driven wild by what they witness and do. One is forcefully reminded of the recency of the 1969 Tate-LaBianca murders, and the change in public consciousness that followed.

A still from “The Blood on Satan’s Claw” (1971), showing three young people walking through a flowering wood [Tigon]

In the final act, “The Blood on Satan’s Claw” attempts a witch trial, but continues only to separate the guilty from the innocent, not by their actions but by contagion. The patches of fur spread from one teenager to the next. Boys are likewise marked, but only the girls are suspected or materially punished for it. The site of the blasphemous invocations where teenagers can scare the living hell out of you is (of course) a ruined church; another symbol of what once was holy made impure by the mere passage of time and the action of nature.

There are those who say a witch is born and others who insist a witch is made. “Claw” suggests a third option: that witchcraft can come upon a person as unbidden and inevitable as puberty, and as impossible to understand. While the requisite sillies of Satan and Behemoth make this theory less interesting, it always fun to encounter a story that escapes a previously-held binary. While the conclusion binds itself with discipline and disappointing stabbery, this piece of the unholy trinity certainly has spirit.

The Blood on Satan’s Claw is available to stream on Pluto.tv

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.