“The gates of hell are open night and day;

Smooth the descent, and easy is the way:

But to return, and view the cheerful skies,

In this the task and mighty labor lies.”

—Virgil, The Aeneid

These lines from the ancient epic poem about the fall of Troy are delivered by Paul Mescal in the newly-released Gladiator II, who stars as the gladiator who is really something else in disguise. Why else would a slave from a Roman colony speak poetry, except to make a point of his noble birth? The point of the verse is that it’s easy to let everything go to shit, while building a world worth living in is an endless and difficult task.

That’s also the point of this film.

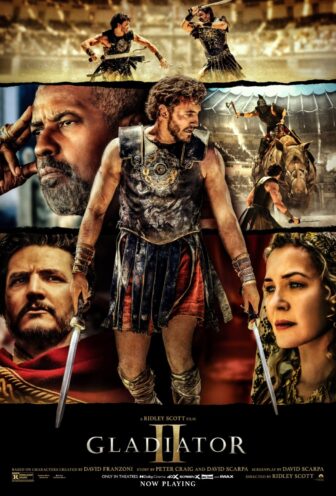

Promotional poster for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II [Paramount]

The film is the sequel to 2000’s best picture, Gladiator; both films are directed by Ridley Scott. The original gladiator with a heart of gold was Maximus, a farmer pressed into service and a soldier who believed himself apolitical (Russell Crowe). In service to the emperor Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), he saw the shady succession of Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), the unstable heir apparent. In a series of blood in the sandal battles, Maximus became more popular (It’s all about popular!, as Glinda says in this weekend’s other big release) than the emperor, and finally manages to killed the laurel-wreathed villain.

There are no masters and virtually no gods in this version of Rome. The pagan city of both the original and the sequel is oddly empty of temples. Gladiator II opens with a Roman naval legion laying siege to the city of Numidia, a northern African port town where our hero and his soon-to-be-fridged wife live. She dies gloriously in battle; he lives to take revenge. Small gestures are made in offering to gods never named, just as Commodus remarked offhand in the first film that he will “sacrifice a hundred bulls” to celebrate a military victory. To whom the sacrifice will be addressed, we never know. In what temple these people worship their “blessed mother” or “blessed father,” we are never shown. Perhaps Scott doesn’t believe an American audience can root for a truly pagan protagonist, even in pre-Christian Rome.

In the 2024 film, Rome is subject to the misrule of a pair of twin emperors: Gaeta and Caracalla (Joseph Quinn and Fred Hechinger, respectively.) These evil redheaded twinks behave like Caligula and look like inbreeding, which raises the question: whose kids are these? Commodus died without heir; his sister Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) hid her son Lucius to protect him from the chaos; and Marcus Aurelius’ line has apparently ended. These purebreds without papers are cut out of the same mold as all knavish and obviously bad rulers in film: hilariously decadent, foppish and dandy, screaming let them eat cake while petting their monkey (who is also a senator). Formidable enemies, they ain’t.

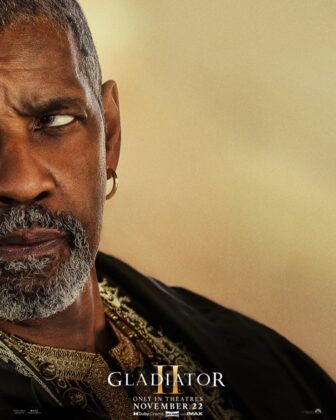

Denzel Washington as Macrinus in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II [Paramount]

Luckily, Denzel Washington is on the scene as Macrinus, a former slave and gladiator turned profiteer. The brightest spot of the film, Washington plays his character with layered subtlety, eschewing the simply ambitious or the purely vengeful, instead reaching for the rage of a class-locked citizen seeking to change his stars by any means necessary. Having bought Hanno (Mescal) and turned him into an arena star, Macrinus believes he can ride the wave all the way to the throne.

Glowering on the margins of all this is a criminally underutilized Pedro Pascal as General Acacius. Having been the one to kill Hanno’s wife, he is introduced first as villain. Later, as we discover him to be Lucilla’s lover, he becomes a more complex figure and perhaps a sympathetic one. But none of these things comes to fruition as the film careens toward its implacable spectacles: a naval battle in the flooded colosseum, a chest full of arrows for our beautiful boy, and a shameless set of flashbacks to the first film to establish what must by now be obvious to anyone paying attention: Hanno is not who he seems to be.

“To few great Jupiter imparts this grace,

And those of shining worth and heavenly race.”

No character in the film moves on to these next lines of Virgil, but they’re present in the mind of anyone who’s read the poem. “Great Jupiter” might be a bridge too far for a film where the deeply religious people of Rome refer only vaguely to “the gods” when they wish to invoke authority or inexorability. Yet the hands of Jupiter are all over their destinies, and ‘shining worth’ is definitely an inherited trait.

(Spoiler warning follows.) Hanno is, of course, the long-lost Lucius, the only true heir to the throne and secretly sired by Maximus. In Paul Mescal (and in a contour palette), the casting gods have found a physiognomy that suggests patrimony from both Crowe and Harris, an uncanny resemblance pointed out and mimicked and underlined and reinforced and outlined in neon and screamed at the audience about a hundred times in the film’s 148 minute run. (We get it! Bloodlines are everything! Somehow, Palpatine returned!)

Lucius has inherited his father’s ability to command an army, though he was only a soldier out of necessity. He’s inherited his grandfather’s stoicism and affection for the senate. He’s inherited both of their abilities to make people love him effortlessly, to the point where they chant his name above the arena despite the fact that he’s presented as one of a number of “barbarians” and no one has told them what his name is. They must do this, because they did it for Maximus. And we must recreate the film that came before.

The Romans must also recreate the Rome that came before. Nearly everyone in this film is obsessed with the Rome that was: the Rome where honor meant something, where the emperor was a scholar instead of a syphilitic club kid in a toga, where the people didn’t go hungry in favor of funding wars, and where the praetorian guard wasn’t holding down the rabble with open brutality at all times. They want to make Rome a republic, or make her great again, or make her into a socialist paradise (it’s really not clear). It is much easier to complain about a bad government than to build one that works. See Virgil for more on this. See Hannah Arendt. See Marija Gimbutas. See all of human history. See the news.

“There is no other Rome,” says Macrinus, this film’s closest thing to a voice of reason. He’s not a republican and he knows that Rome will not become a merry and peaceful democracy in the 200th year of the common era. He alone seems to understand that the chaos at the heart of this empire is the rule, not the exception, and that these events fall perfectly into the jagged line of Roman history. Even Lucius, who seeks to free the city and not to rule it, is much too optimistic about what’s to come. “The slave dreams not of freedom,” says Macrinus, quoting Cicero. “The slave dreams of a slave to call his own.”

Paul Mescal as Lucius and Pedro Pascal as Acacius in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II [Paramount]

Gladiator was a famously ahistorical film, playing fast and loose with names and dates and even the uniforms the legions wore in battle. Though Gladiator II is just as detached from the real history that it loots at will, it seizes (at length, and only by accident) on a great truth about the Roman Empire and all empires. Chaos, destruction, and rule by the worst impulses known to mankind are not aberrations. They are our default state. Fascism and kakistocracy are not disasters that come from nowhere; they’re the result of those default conditions.

But to return and view the cheerful skies, the good days, the Pax Romana, the fully automated gay luxury space communism of our dreams, is the result of boring and difficult work in creating an equitable and beautiful world that rewards merit and punishes or at least silences the cruel and inhumane among us.

Gladiator II posits that a better world is possible, and worth fighting for. It points out how important nepo babies like Scott’s three children, all film directors, will be to that world. It shows us a jaggedly broken and bloody window through which we can see that world for a second as the train of history runs us over, taking us into the dark tunnel of war and empire on the tracks that will eventually lead us home.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.