MIAMI – Archaeologists have made a groundbreaking discovery in the Colombian Amazon: a colossal rock adorned with extensive ochre paintings depicting animals and human figures, estimated to be around 12,500 years old. This extraordinary find not only enriches our understanding of the diet and mythology of the continent’s first inhabitants but also offers a glimpse into the intricate relationship between these early people and the diverse ecosystem of the Amazon.

The research, published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology this week, was conducted by an international team of archaeologists from the University of Exeter, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

A view of the Cerra Azul. Photo Credit/Courtesy: University of Exeter

Their study focused on Cerro Azul, a prominent tabletop hill in La Lindosa, located along the Guayabero River in the northwest of the Department of Guaviare, Colombia. This region, characterized by a unique intersection of savannah and tropical forest environments, forms the border between the Amazon rainforest to the south and the savannahs to the north. Archeologists have known about Cerro Azul but the region had been off-limits due to political instability.

The Colombian Amazon is home to one of the richest collections of rock art in the world, with vibrant ochre images of human figures, handprints, animals, plants, and geometric designs adorning the rock outcrops of the Serranía de la Lindosa, Chiribiquete, and the Inírida River region. These images serve as a visual record of how Indigenous communities interacted with their environment and how they constructed and perpetuated their socio-cultural worlds.

The discovery at Cerro Azul is particularly significant as it represents some of the earliest evidence of human presence in western Amazonia, dating back over 12,500 years. The rock art was created using red ochre pigments on the rock walls of Cerro Azul, and while the images have yet to be accurately dated, they are believed to have been made as far back as 10,500 BCE.

The wall art of Cerro Azul shows many animals but with some notable omissions. Photo Credit/Courtesy: University of Exeter

The artwork includes vivid depictions of deer, birds, lizards, turtles, tapir, and other animals, offering a glimpse into the rich biodiversity of the region and the early inhabitants’ interactions with these creatures. However, the study reveals that the animals depicted in the rock art do not necessarily reflect the diet of these ancient peoples. Zooarchaeological analysis of animal remains recovered from nearby excavations showed a diverse diet that included fish, small to large mammals, and reptiles such as turtles, snakes, and crocodiles. Yet, the proportions of animal bones do not match the representation of animals in the rock art, suggesting that the artists did not merely paint what they ate.

For instance, while fish were found abundantly in the archaeological remains, they appeared only rarely in the rock art. Similarly, felines, despite being apex predators in the region and holding spiritual significance for some tribes, were notably absent from the images. This discrepancy indicates that this rock art served purposes beyond mere documentation of diet, likely reflecting the spiritual and mythological beliefs of the early Amazonian people.

Cerro Azul hosts 16 “panels” of ochre drawings, several of which could only be accessed by researchers after strenuous climbing. These panels include over 3,200 images, most of which depict animals such as deer, birds, peccary, lizards, turtles, and tapir. The largest of these panels measures 40 meters (~130 feet) by 10 (~32 feet) meters and contains over 1,000 images, while the smallest panel, covering 60 square meters (~645 square feet), features 244 well-preserved red paintings.

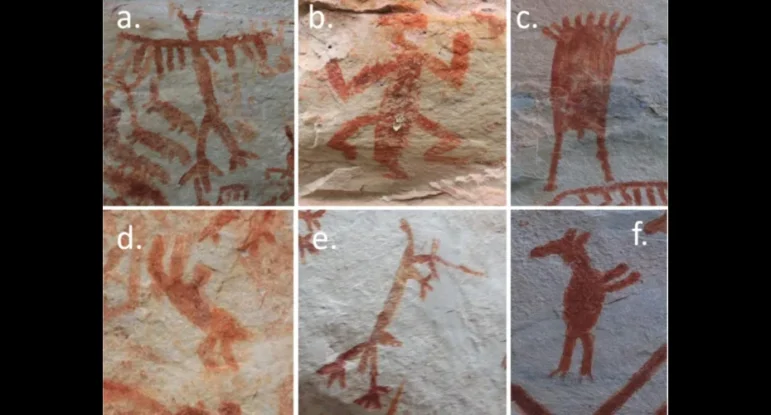

Human-animal hybrids described by Indigenous informants: a) avian/human at Las Dantas, b) lizard with round, human-like head, c) bird/plant/human, d) sloth/human, e) Unknown quadruped, f) Deer/human. Photo Credit/Courtesy: University of Exeter

The researchers utilized drones and traditional photography to document these images, providing a comprehensive record of the artwork. Their findings offer valuable insights into the complex relationships between the early Amazonians and the animals they depicted. The context in which these images were created suggests that animals were not only a source of sustenance but also revered beings with supernatural connections, requiring complex negotiations from ritual specialists.

Some of the figures in the rock art combine human and animal characteristics, hinting at a complex mythology of transformation between animal and human states—a belief that persists in modern Amazonian communities. This suggests that the early inhabitants of the region had a deep understanding of their environment and the various habitats within it, including savannahs, flooded forests, and rivers. Their ability to track and hunt animals and harvest plants from these diverse habitats reflects a broad subsistence strategy that was essential for their survival.

The paintings also offer a glimpse into the ancient peoples’ broad understanding of the various habitats in the region and their intimate knowledge of the flora and fauna. According to Javier Aceituno, one of the study’s authors from Medellín, Colombia, the early Amazonians possessed the skills necessary to thrive in this challenging environment. They had an intricate knowledge of the region’s habitats and were adept at utilizing the resources available to them.

While the exact meaning of these images remains uncertain, they undoubtedly provide greater nuance to our understanding of the power of myths in Indigenous communities. As Jose Iriarte, a study co-author from the University of Exeter, noted, these images likely played a crucial role in shaping the spiritual and cultural identity of the early Amazonians.

“These rock art sites include the earliest evidence of humans in western Amazonia, dating back 12,500 years ago,” says Dr Mark Robinson, Associate Professor of Archaeology in Exeter’s Department of Archaeology and History. “As such, the art is an amazing insight into how these first settlers understood their place in the world and how they formed relationships with animals. The context demonstrates the complexity of Amazonian relationships with animals, both as a food source but also as revered beings, which had supernatural connections and demanded complex negotiations from ritual specialists.”

The researchers caution against imposing contemporary worldviews on the creators, particularly those that might “undermine the complex spirituality” of Indigenous groups. Instead, they urge us to value the ancient artwork for its insights into societies that viewed the relationship between humans and nature as deeply reciprocal and interconnected.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.