This is part two of our interview with Danica Boyce, host of the podcast Fair Folk. Please find part one of our conversation here.

As I was driving home from my coven’s Beltane celebration this past May, I was listening to an episode of Danica Boyce’s Fair Folk podcast about May traditions. Boyce introduced a folk song during the episode, Lisa Knapp’s version of “Don’t You Go A-Rushing,” a riddle-song for the May Day season:

How can you have a chicken without any bone?

How can you have a cherry without any stone?

How can you have a ring that has no rim?

How can you have a baby with no squallin’?

I was so captivated by the performance that I knew I wanted to hold Beltane the next year, specifically so I could work that song into the ritual. When I saw that Boyce would be teaching a course on Pagan ritual songs, I knew I wanted to hear more about her particular approach to music, ritual, and Paganism, which led to this discussion.

Here is Boyce’s own biography:

Danica Boyce is a medievalist and folklore researcher with a masters in Medieval Studies and a bachelor of education with a focus on Indigenous pedagogy. She takes a de-colonial approach to the revival of traditional cultures. For the past seven years she has produced the Fair Folk Podcast, a research-based show sharing accessible information about Paganism, folklore, and folk song. She has traveled to research and take workshops in folk singing in places like Iceland, Finland, Georgia, and Lithuania.

She is also a practicing Pagan with a scholarly yet experimental approach to historical materials, and an open mind to multiple ways of seeing the world.

Interested readers can find more information on the course, which begins on January 14th, here.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Danica Boyce by dolmens in Drenthe, Netherlands, in 2019 [Quinn McCord, courtesy]

TWH: Let’s segue into talking about music. The reason I got in touch with you for this interview is that you’re soon offering a course on Pagan Ritual Song. You’ve mentioned that this is something that has been a special interest of yours for the past couple of years. What led specifically to thinking about song and ritual?

DB: I’ve always had a sense, an instinct, that song is really important. I think most people can relate to the fact that music communicates something beyond what language can, and singing specifically is this really accessible form of music: everybody can sing, whereas not everybody can play an instrument. It has this real appeal of being a sort of universal musical expression.

I have a friend, whose name is Joseph Jordania. He’s a music historian, but he also dabbles in evolutionary biology. He has this theory that humankind sang in harmony before we even had articulated speech. It’s one theory, but it’s really inspiring to think that singing is something absolutely innate to our humanity and our ability and our embodiment. And it’s only in being trained out of singing that we stop doing it in our daily lives. When we’re young, we revel in song.

When I started making the podcast, including music seemed obvious to me, because I’ve been interested in folk music for a long time, and I’ve had a radio show before about music. It made sense to me to combine folklore and folk songs on the podcast. So I’ve always included folk songs on the podcast, and sometimes they’re the main focus.

I’ve been fascinated with the question of, “what songs are Pagan? How can we prove that they’re Pagan?” There’s an unending debate about whether a lot of older songs or folk songs with seasonal or mythological themes are authentically Pagan or not. And then it occurred to me one day that a song is Pagan when we use it in a Pagan way.

I would just take a folk song, the melody maybe, and change the words a little bit so that it was a prayer to a tree or to a god, or I would take the words to epic poetry and put them to a folk melody, and suddenly I would have a Pagan song. I realized that it’s actually not that complicated: if you believe that you can make a Pagan hymn, then tomorrow you have one.

I see all these other religious traditions, like Christianity, for example – they’re full of religious, spiritual songs for worship. And Paganism really lacks those songs, or at least, Pagans lack the permission to use those songs in a spiritual context. We do see a lot of Pagan music groups arising, like Heilung or Wardruna, who are composing new songs that are Pagan. But rarely are those songs simple or usable in a group in a casual context. Rarely could you take out a Wardruna song at a campfire and expect everyone to sing along. Whereas folk songs are structured that way: they are simple, accessible.

We are modern Pagans, we’re practicing. We don’t have to prove to anybody that our religion or religions are real; we can just go ahead and make a song Pagan if we like the song, and it’s relevant to our context and purposes. And the oral tradition of folk song is an excellent resource for Pagan practice if we only look at it that way.

TWH: I think because I’ve grown up in a society where originality and copyright are seen as the most important things in any kind of creative pursuit, my instincts are, “oh, well, I can’t use someone else’s melody.” No. You hear a traditional tune, and you might think, “Oh, that’s ‘Greensleeves,’” but then you might also think, “Oh, that’s ‘What Child is This?’” Using that same method to create new Pagan songs is on the one hand very obvious, but on the other, gets to some of your points about not being able to see past our current assumptions about originality, about what kind of “property” is available to us.

DB: It is a huge difference between modern western capitalist culture and culture at all other times on earth that originality is highly prized, and that ownership of intellectual property exists. I did a master’s in medieval studies, and the original author of something is almost never known; people copied as a virtue, and this is the ethos all of the traditional songs came to us from as well. There were potentially hundreds of versions of each one, and everybody made it their own.

Just thinking about “Greensleeves” – maybe the text, maybe the original words to this melody that you’re referring to, was some terribly boring account of a war in the most boring part of England. And somebody was like, “well, that won’t do. I’m going to make it a love song.” And then it’s a hit, and then, later, it’s about Jesus. This is how culture has always worked. If something is good, then it’s an honor that it will grow and change and spread. That’s how it sticks around, because we didn’t have recordings before. We just had people with enthusiasm.

That is how culture will survive after we don’t have the internet as well, is when people take something on, take ownership of it and give it away for free. All of the songs that I make up and share online, like these Pagan ritual chants – I hope people take them and change them. Of course, it’s helpful if they say, “I learned this from Danica,” but it doesn’t really matter. I’m going to die one day and I hope that song outlives me. That would be the most amazing thing ever. I don’t care. I’m not going to make $2 off of it. Please let the Pagan songs live at the expense of my intellectual property.

Though saying that might bite me in the ass someday. (laughs)

![]()

We hate to keep asking, but it is serious. Costs have hit us too.

We are grateful to our readers for your support, however it manifests. Right now, we need readers who can help fund Pagan journalism to help us continue serving the community. This is the type of story you only see here. This is how to help:

Tax Deductible Donation | PayPal Donations | Join our Patreon

We remain one of the most widely-read news magazines within modern Paganism, and our reporters and columnists remain dedicated to a vision of journalism for and about our family of faiths.

You can also help us by sharing this message on your social media.

As always, thank you for your support of The Wild Hunt!

![]()

TWH: From following your work, I know you have spent a lot of time going to different communities and learning from them in the past few years. What has the research process looked like in preparing this course? Especially the balance between “academic” research, looking things up in historical records and so on, and “field” research, where you are visiting these communities and talking to people in the present.

Participants in a Romuva ceremony [Mantas LT, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

DB: It’s been a combination of your standard boring research, like reading articles online from academic journals, and traveling to do field research for this podcast. I’ve been going back and forth to Europe since 2016, to places like Iceland and Lithuania, and Finland and Georgia.. And I had always been looking for Pagan themes in folk songs in that process. But it really struck me when I got to Lithuania specifically, and started hanging out with this Pagan religious group called Romuva, that folk songs specifically could not only be a tool for ritual, but a source of information about ritual, or the very core of the ritual.

So this group Romuva takes Lithuanian folk songs, which have a lot of mythical themes in them already, and builds rituals around them. It will be a group singing together around a fire, dancing in a circle, with a folk song that’s often been adapted to Paganism, or sort of re-Paganized. I’d never seen folk song employed in this way before.

There’s a lot of people trying to be really careful to not say something’s Pagan when they don’t know for sure how long it’s been around, but these people were just quite boldly taking the cultural heritage of Lithuania and saying, “this is Pagan.” And in Lithuania, there is a bit more pride in their Pagan past. It’s easier for them to embrace. There’s also a lot of Catholicism there, but Paganism is more positively viewed than it would be, say in North America, for example, or Germany.

But being in those rituals, singing those songs – they were quite easy to participate in, even though I didn’t speak Lithuanian, because there was this emphasis on repetition and call and response and accessibility. It’s because they’re folk songs, they’re simple. It just blew my mind, that it was like I didn’t have to “find the Pagan roots” within a folk song. I could reverse engineer it. We could, all of us could.

That reminded me of, to a degree, of the Indigenous groups in North America who are also – again, to a degree – having to reconstruct traditions that have been partially lost. It felt really invigorating and beautiful, and that’s what sort of changed how I saw folk song and Paganism relating. It made me really inspired to do the same thing.

The old town in Tórshavn, Faroe Islands, 2004 [Erik Christensen, Wikimedia Commons, CC 3.0]

TWH: Now I’m thinking about language. When I visited Iceland, I went out drinking with some people from Ásatrúarfélagið, and they started singing these Faroese ballads with all kinds of Pagan material in them. Now, I can just about order a cup of coffee in Icelandic, and Faroese is close, but it’s not the same thing. I could hear the refrains you’re talking about, but I certainly couldn’t jump in and keep up. How does the language element work into these songs, especially languages we may not speak? Does something get lost in translation?

DB: When it comes to addressing folk songs, Pagan songs, et cetera, that are in other languages, it is a challenge. I find my first instinct is to give in to perfectionism and think, “well, I could never translate this, therefore it won’t get translated.” Or that I could never translate this well enough to honor the tradition, which would cause me to give up.

But if I just say, I have this friend who speaks the language, and I ask them, could you translate this song for me? Could you tell me what the song is about? Then take that information – and I’m an English teacher, so this is easier for me, but – take the meter that the song is in. Just listen. You don’t have to understand meter, but if you listen to the rhythm of the song and notice where the rhymes are, you could take the information of what’s in the song and make an approximation of it in English, which is 100% better than having no approximation of it at all. And you can run it by your friend and say, is this any good? Does this convey the general idea behind this song? And voila, maybe you now have a Pagan song in English.

I just think making connection with things and building this repertoire is so much more important than perfection, than trying to aspire to an academic standard. And we also have a lot of amazing tools right now. Google Translate, not for some languages, but for others, is remarkably useful. And if you have a second person, if you can find someone who speaks the language – you might find them on Reddit, you might find them on Instagram – you can get a lot done.

TWH: So let’s talk about the course itself. How’s it structured? And how are you planning to approach it pedagogically?

DB: Well, there’s five units, and in each unit, I’ll start by giving the history of a particular type of song and give some information on the history of a type of song or a genre. And then in the second part of each lesson, I’m showing people the tools that you need to either learn or create that kind of song for yourself or utilize that historical source. So there’s the learning in the sort of lecture sense, and then there’s the application of it in a rather low pressure way. It’s more of an invitation – here’s what you would need if you want to engage this in this way. It’s not like a classroom where you’re going to have homework and be in trouble if you don’t do it or something.

TWH: It’s not going to show up on your transcript if you don’t make up a song.

DB: Right!

First, we’ll cover ancient song. What songs do we know about from pre-Christian times, the actual Pagan history, what were skalds singing in the halls? What texts do we have that remain, at least for the most part, from the pre-Christian era? Then the second unit is about charms and prayers. This is one of the most common forms of address to a god or a saint or a deity of any kind. That is really common in folklore and is quite a simple structure. And so I want to show people how to create a charm or a prayer that’s a song, based on the conventions of the past.

Then in the third unit, I’m going to teach about ballads, supernatural ballads, specifically. I think that ballads get a bad rap as being this kind of boring kind of poem that you might not even encounter in English class anymore. But there happens to be a beautiful collection of narratives in song that tell the story of humans encountering otherworldly beings, like the king or the queen of the fairies, and going into other worlds. As you can tell, I’m kind of obsessed with ballads, because they have this regular structure to them, they have all these chant elements. They could be used in a ritual context quite easily. We just aren’t framing it that way because it’s much safer to think of a ballad as just a storytelling container. But the origin of ballads is not only storytelling, it’s also group circle dancing and singing, which can be very pagan indeed!

In unit four, I’m going to be teaching about songs for specific occasions, like say like the sunrise or the sunset, or a toast at a meal. The more that you think about occasional songs, the more examples you can come up with moments in your life when you might want to sing: in blessing or in opening of a ceremony or in a rite of passage; there could be a song for any occasion. So I’m going to be teaching about songs for occasions and inviting people to find a moment that they find particularly meaningful and to create or learn a song for that situation.

And then finally, the last unit will be the one that if folks listen to my podcast would probably be expecting the most, and that is songs to honor the cycle of the year – seasonal songs. We especially become aware of those in the middle of winter, when we start hearing carols all of the time. Pagans are suddenly looking for songs about the solstice and coming up dry. But there’s a song for every season of the year in folk tradition, and it’s so readily available to start thinking about these songs in a Pagan context. There are already so many examples – think of the song John Barleycorn, about a personification of the grain being murdered and made into beer.

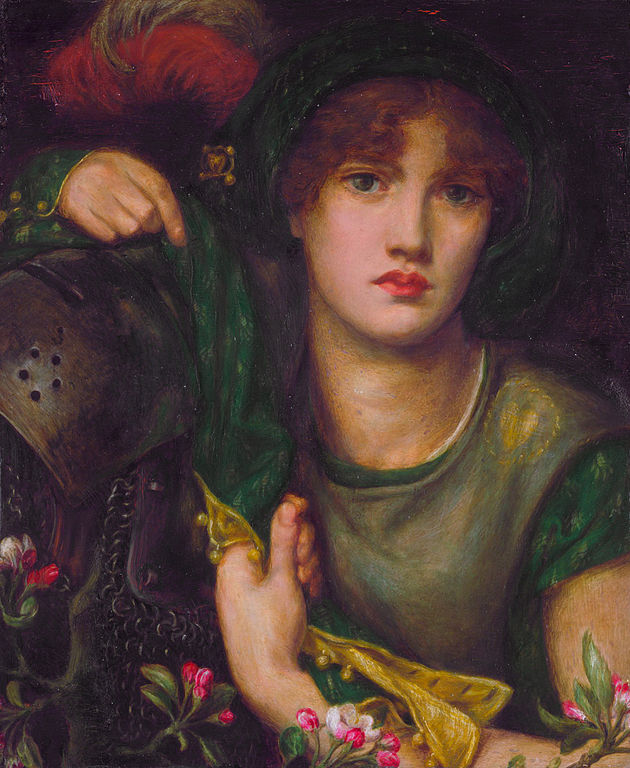

“My Lady Greensleeves,” Dante Gabriel Rosetti, oil on panel, 1863 [public domain]

TWH: What are you hoping to see students in the course do with this material?

DB: Oh my gosh. I want them to go out into the world and sing as much as they can. I want them to sing praise to the living world, and to feel empowered to do that, to use their voices, to worship life on earth, and to feel confident in doing that. To feel like they’re allowed to make songs, and to have songs, and to be engaged in that deep and vibrant way that our instincts tell us that our ancestors were able to do, before industrialization. Because people used to be singing everywhere, all the time, in all kinds of contexts. And not because they were specialists at it, but because they were alive and they wanted to participate in the world in a loving way.

TWH: As you have been engaged in this research, how has all of this work affected your own ritual practice? How has music entered or affected your own ritual practice?

DB: That’s a great question. I almost never do ritual now that isn’t somehow related to song. To me, songs have become ritual, and ritual has become song, and it feels a lot more organic. I used to think of ritual as something that you had to plan and that you had to have other people coordinated with, and you had to have props. And now I’ve started to feel it more as something that arises organically almost out of my body or the earth, which is just this often spontaneous singing, because it’s the most basic and portable of offerings. That feels like the truest approach to paganism, to me, is what is the most ready to hand and most sincere tool that I have to offer to the animate world. And that is song, in my case. So I guess I’ve become increasingly focused on song as a ritual tool, you could say.

TWH: A ritual form, it sounds like.

DB: A ritual form. Yeah. Thank you for that. I would say I would agree that now I see song as a form of ritual, and it’s my favorite form of ritual. It’s the main one that I engage in. I do divination and things, like with my tarot cards. I don’t sing to them, but maybe I should, now that I think of it.

Interested readers can find Danica Boyce on Instagram and join her mailing list at Flodesk. The Pagan Ritual Song course begins on January 14th; more information can be found here.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.