TWH – Up until the early 20th century, mourning was a visual, community activity. Death wasn’t removed from everyday life, taboo to speak about, or hidden from children as it is today – it was accepted and understood. In less than a hundred years, we’ve changed our perspective and relationship with death so extremely that it has led to a less-than-healthy fear and misunderstanding of death in the wider culture. This might yet be restored, however, if we understand the mourning practices we lost, and how to bring them back.

In the wider Witch, Pagan, Druid, and some other minority religious communities, death is much more discussed and accepted. We can find common ground across most traditions under this umbrella. The acknowledgment of death as a part of life, the understanding that our time on this earth is just one of many journeys we’ll take, and finding comfort in our connection and return to the earth are all commonly held beliefs amongst our varied community, in one way or another. In society at large, particularly secular, Western popular culture, death is not so discussed or even thought of. But this gap can be bridged by recognizing that when we are discussing the Old Ways, many of them, when it comes to death rites, were Christian, Jewish, Islamic, and secular, too.

A grave at the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome [Photo Credit: M. Tejeda y Moreno]

Mourning practices are the things done leading up to and after the death of a loved one. These include funerals and viewings, still commonly administered (albeit differently than our ancestors would have done, as we’ll see) as well as activities like wakes, the washing of the body, grave-tending or digging, and mourning dress for the home and family of the deceased. Until the advent of the modern funeral home, the funeral was held at the home of the deceased or simply at the gravesite. When someone died, their body didn’t leave with the coroner. It was the responsibility of the family to clean and prepare the body. This might sound like an inconvenience or a challenge for the aggrieved to achieve, but it actually provided a much-needed period of closure. By preparing the body oneself, it enables the aggrieved to slow down and understand that this has indeed come to pass. It gives one time alone in contemplation, and to talk to the body.

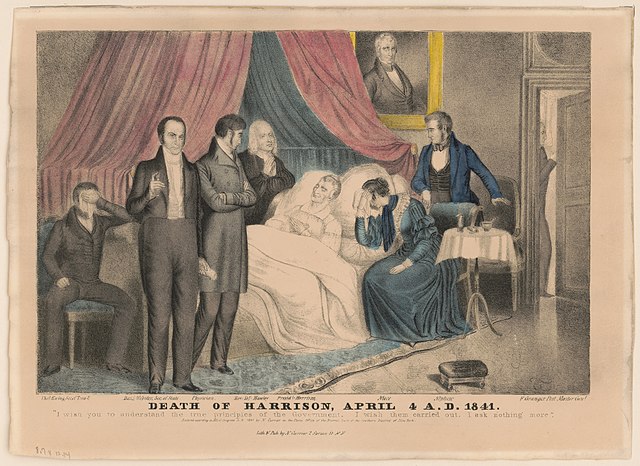

Following this period of preparation, the body would be laid out in the home for public viewing, often lasting several days. This gives people much more time to come and pay respects to the deceased, rather than the two-hour viewing held optionally today. Being at home also gave people a chance to support the household of the deceased by bringing food, helping to facilitate the event, or keeping the house clean for them. It quickly becomes a community activity when a member dies, rather than an ostentatious, somewhat-performative event hosted by the aggrieved. These long viewing events were called wakes because the family wanted to make sure the person wouldn’t wake before being buried; and although this is unlikely to be an issue today, having a wake with or without the body of the deceased today can provide closure and enable people to take care of the deceased’s household.

Death of President Harrison [public domain]

Funerary services were still provided by outside officiants, traditionally, but in the home of the deceased, or at the gravesite, making the process less officious, more affordable, and simpler – taking so much weight off the mourners. A service often provided, particularly in the 1800s, was the hiring of mutes: tall gentlemen dressed in black who stood by the doorway of the house throughout the wake and funeral to be sure visitors would know a death had occurred. This was just one silent cue to the emotional state of the household we’ve lost with mourning traditions.

The act of wearing mourning clothing was a silent sign to all around that that person recently lost a loved one. Simply wearing black achieves this, but as mourning clothes are so uncommon today, it might go unnoticed by society. Traditionally, when someone was seen to be in mourning, it was a silent cue to treat them kindly and gently: a cue it can be hard to signal today without rehashing all of the loss and sadness that goes along with talking about a loss.

Legally (and hygienically) a week-long wake might be difficult to do today, but mostly, these are practices we could restore. With the interest of supporting the grieving being the main object of these practices, it becomes clear that by neglecting them, we’re neglecting the grieving process. As pagans, these are practices we can adapt and support, with coven leaders giving funerals and hosting wakes that support the family. Wearing black and ceremonial jewelry can help us feel connected to the deceased and invite their spirits to stay with us longer. But most importantly, showing up for each other in these or other ways in the days following a loss is important for our grieving process: continuing to have conversations with and about our loved ones beyond their time on this earth is vital, healthy, and the surest way of processing grief.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.