The Smithsonian Institution has been holding a disturbing and unethical collection of human remains from public view since the early 20th Century.

The Smithsonian Institution was established in 1846, thanks to a bequest from James Smithson, a British scientist, who left his estate to the United States to create an institution for the “increase and diffusion of knowledge.” The U.S. Congress accepted the bequest and founded the Smithsonian Institution as a trust to fulfill Smithson’s vision.

Since its founding, The Smithsonian has become a group of museums, research institutions, and educational organizations located primarily in Washington, D.C., but with some facilities in other parts of the United States. It is now one of the world’s largest and most well-known museum and research complexes.

The Smithsonian’s eclectic holdings contain some 154 million items – but few as grisly and horrifying as the “racial brain collection.”

The Washington Post broke the story last month: the Smithsonian has been holding a collection of human brains primarily taken unethically from Black and Indigenous people.

The stories are beyond understanding for modern ethical standards and echo the horrific Tuskeegee Syphilis Study. One such story involves the death of a young Sami woman from tuberculosis, whose brain was mailed to the Smithsonian by her physician in Alaska.

The Post wrote: “Ales Hrdlicka, the 64-year-old curator of the division of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Museum, was interested in Sara’s brain for his collection. But only if she was ‘full-blood,’ he noted, using a racist term to question whether her parents were both Sami.”

The Smithsonian Museum of Natural History [Photo Credit: Melizabethi123 CCA-SA 3.0]

There are 254 other brains in the Smithsonian, part of a 30,000+ collection of human bones and body parts currently held by the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum. Some 14 others were sent to other collections. The majority were taken without consent.

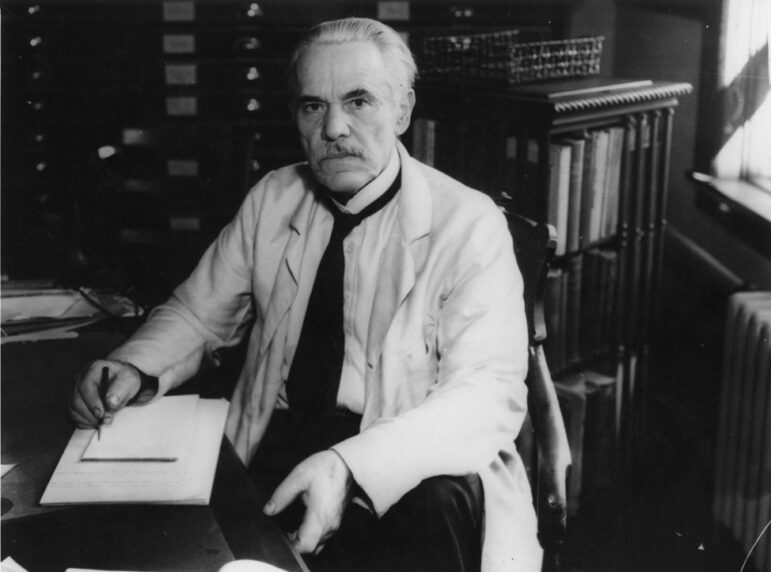

The collection of brain and body parts was championed by Aleš Hrdlička, a prominent Czech-American anthropologist, known for his significant contributions to the field of physical anthropology and his work on the study of human evolution, skeletal biology, and human migration to the Americas.

Aleš Hrdlička (1930) [Public Domain]

Hrdlička died September 5, 1943, and his interest in brains and body parts was neither benign nor scientific, certainly by modern standards. His methods included dismembering decomposing bodies and discarding infant bodies he found to be useless. His beliefs dominated his science: he was seeking evidence of white superiority. His racist work was subsidized by U.S. taxpayers.

Hrdlička was an advisory member of the American Eugenics Society, an organization dedicated to “furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations.”

Hrdlička “considered people who were not White to be inferior and collected their brains and other body parts,” according to another Post story, “convinced that he could decipher race primarily through physical characteristics, according to his writings and speeches. He was celebrated in his time, testifying before Congress and as an expert witness in court, and sought out by the FBI to help with cases.”

Hrdlička was widely considered an expert on human race variation. His views on race influenced the media and even U.S. government policies. In a famous lecture for the American Association for the Advancement of Science on “The Origin of Man,” Hrdlička offered his theory that the cradle of humankind is not in Central Asia but in Central Europe.

Hrdlička did not apparently ever have any research of his own on the harvested body parts. He simply said that the research shows the superiority of white brains.

Earlier this year, the Smithsonian released a statement that it had organized a task force with the aim of crafting a comprehensive policy that deals with the future management of human remains housed within its museum collections. The primary objective of this task force is to foster respectful engagement with the descendants and communities related to these remains and to formulate a cohesive Smithsonian-wide policy for the proper treatment of such human remains.

The statement said that in 2022, the Smithsonian introduced a policy known as “Shared Stewardship and Ethical Returns,” which permits collaborative stewardship arrangements for collections and the potential return of collections based on ethical considerations. Concurrently, the Institution acknowledged the necessity for additional policies pertaining to the human remains under its care. Consequently, this newly formed task force will establish guidelines that pertain to the ethical acquisition, preservation, utilization, and disposition of human remains.

The Smithsonian has now begun the task of locating family members and repatriating body parts.

This task force, the statement said, represents a significant step in the Smithsonian’s ongoing commitment to addressing its collection of human remains. Since the enactment of the National Museum of the American Indian Act in 1989, the Smithsonian has successfully repatriated over 5,000 individuals’ remains. The National Museum of Natural History implemented an international repatriation policy in 2015 and introduced a policy in 2020 for the return of culturally unaffiliated Indigenous remains. The forthcoming policy to be developed by the task force will encompass all human remains held by the Smithsonian.

“At the Smithsonian, we recognize certain collection practices of our past were unethical,” said Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch III. “What was once standard in the museum field is no longer acceptable. We acknowledge and apologize for the pain our historical practices have caused people, their families and their communities, and I look forward to the conversations this initiative will generate in helping us perform our cutting-edge research in a manner that is ripe with scholarship and conforms to the highest ethical standard.”

But not all brains are accounted for. The Washington Posted reported that when they asked about locating those brains, “The Smithsonian declined to research the status of some of those brains and said it would be unable to account for all brains because of prior collecting and documentation practices.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.