I vividly remember my first visit to the Louvre museum, when I must have been no older than nine or ten. The massive complex, almost the size of small city, cannot be explored in one visit, and even given subsequent trips there, I myself must only have seen at most a quarter of it. So when, after going down Pei’s iconic glass pyramid, I was let loose by my mother, I went straight for the big hits – namely the Early Modern paintings from the Renaissance to the early 19th century, where, among others, the “Mona Lisa” was located.

On my way there, wandering the titanic hallways of the world’s largest museum, I suddenly came across a ridiculously massive (and somewhat pompous) painting: “The Coronation of Napoleon” by Jacques-Louis David. After admiring the solemn work for a while, I took a stroll down the aisle, only to be met, at the next corner, by an ever more massive painting, “The Wedding at Cana” by Veronese.

Little did I know, then, that this second work, not only larger, but also significantly more colorful, lively, and engaging than the first, had been looted by the forces of Napoleon himself. Indeed, the Emperor, while mostly known abroad for his tactical acumen, was also immensely concerned with art and how it could help expend his influence. So, when Napoleon lead the armies of Revolutionary France outside of his borders, to Egypt and Italy in particular, he kept his eye open and stole numerous artifacts and artworks. Those ended up exposed in various museums like the Louvre.

Following the defeat of Napoleon, “The Wedding at Cana,” like most plundered art that had made its way to France, was supposed to be taken back to its country of origin. Numerous artworks, however, avoided repatriation due to being held in smaller, out of the way institutions, or simply hidden away by reluctant conservators. “The Wedding at Cana,” however, remained in France on the grounds of the supposed brittleness of the canvas and, by a rather ironic twist of fate, ended up exposed right by the most sumptuous propaganda piece glorifying the man who took it from its home.

If I have decided to reminisce about this rather minor childhood memory, it is because in the past couple months and years, the topic of repatriation of looted art and artifacts has become mainstream discourse. Numerous media outlets, including The Wild Hunt have been thoroughly covering all aspects of this complex issue.

Jaques Louis David’s “Coronation of Napoleon.” Public Domain.

As for myself, a lowly museum worker and museophile, I did tangentially muse on the topic in a piece some two years back. In that article, I mostly talked about the place of artifacts in museums and how complicated it is to negotiate the preservation and communication of ancient heritage when it is seen as sacred by a section of the public.

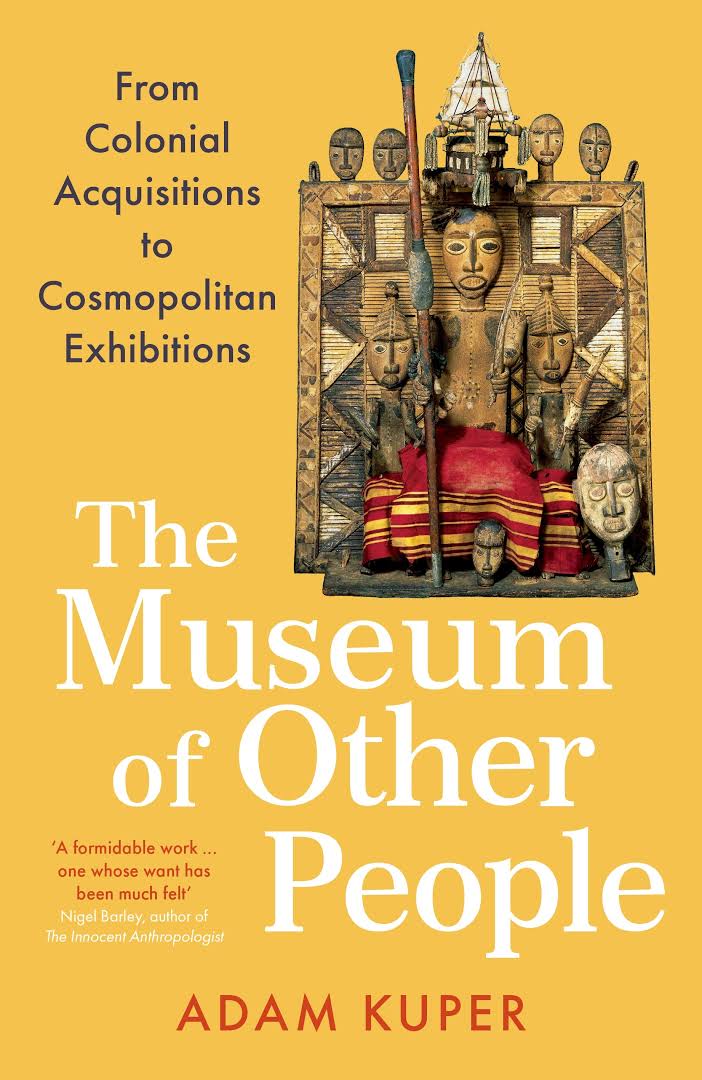

However, after finding, in my museum’s library, no less, a little book called The Museum of Other People, I began to think further about the importance of repatriation, especially in a religious, Pagan context. My previous article was titled “Do Gods Belong in Museums?” Now I was challenged to think in new ways: what can make museums welcome for gods and sacred paraphernalia? I will try my best to expound on this question in the following paragraphs but first I will need to shortly introduce the book that started this train of thought.

The Museum of Other People, which came out just a few months ago, was authored by famed cultural anthropologist Adam Kuper. Despite being written by an anthropologist, the reader will find that The Museum of Other People is (praise the gods) mostly free from the rather byzantine academic language that most writers in this field coat their works with. In lieu of contrived theories and abstract philosophical musings, this book offers a series of thematic chapters, mostly arranged chronologically, focusing on the origins of museum culture in the western world.

Despite being neither a historian nor a museologist, Kuper manages to paint a vivid and factual portrait of the museum world and the changes it experienced over four centuries. Unsurprisingly, given the author’s credential and the title of his book, The Museum of Other People is especially concerned with ethnological museums and collections and how they came to be in the previous two centuries.

In the second part of the book the author pivots his narrative and takes the topic of looting and repatriation by the horn. Starting with the aforementioned Napoleonic looting campaign, which some scholars credit as being the opening salvo of modern art theft, Kuper spends considerable amount of time discussing museums’ repatriation policies and how specific exhibits, artworks, and institutions were, and continue to be, transformed in the process.

Adam Kuper’s book, released by Profile Books.

When going through the concluding chapters of The Museum of Other People, it becomes quickly apparent that Kuper views the so-called “decolonial” advances in the museum with much skepticism. While it would be easy to dismiss this criticism outright, he brings forth numerous arguments against categorical repatriation.

One of the most compelling of these is the case of the Cyrus cylinder, an artifact of considerable historical and symbolic significance: it chronicles the work of Cyrus the Great, leader of the Persian Achaemenid empire, especially concerning the worship of ancient Mesopotamian deities, law-giving and temple-building. The cylinder was discovered in the late 19th century by a team working for the British Museum, which received the artifact and has held unto it since then.

Later, when the Pahlavi dynasty took over Iran, the government started to make use of the memory of ancient Persian dynasties and empires in order to prop up and glorify its rulers. Thus, the Cyrus cylinder was elevated as a kind of national symbol, especially after it was loaned to be exposed in Teheran in the early 70s. Following the Islamic takeover of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq war, the new leaders of Iran pivoted to other symbols and narratives, but in the early 2000s, talks with the British Museum resumed for a loan of the cylinder. This was especially notable because, back in 1971, some Iranians had campaigned for the artifact to be permanently repatriated.

Despite these previous disturbances and the challenges associated with working with the hardline Iranian government, the British Museum eventually agreed to send the Cyrus cylinder to Iran in 2010. While the exhibition itself was apparently a success, a number of state-affiliated clerics publicly denounced the exhibition, comparing the showcase of the cylinder to pagan idolatry. According to Kuper, this controversy played a role in a later event where the then-director of the National Museum of Iran, where the cylinder had been exposed, was dismissed, arrested, and jailed. This anecdote, centered on a very pagan artifact, illustrates well the complexities inherent to the question of repatriation and collective ownership of ancient heritage.

A close up of Cyrus’ cylinder. Photo by wikipedia user fæ, shared through Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Should the state of Iran, a hardline totalitarian Shia Muslim government own a two and a half millennia old relic of a polytheistic emperor, just because he, like them, spoke a Persian language? But, on the other side, why should the British Museum own it, then?

As opposed to numerous other items which have indeed been obtained through less than legitimate means (such as the Parthenon marbles), the Cyrus cylinder was obtained legally: The British Museum obtained an authorization from the Ottoman authorities to start the dig, which actually took place in Babylon, the seat of an ancient Semitic nation, now located in Iraq. To make things even more complicated, the dig was directed by Hormuzd Rassam, an ethnic Assyrian Christian.

To attempt to determine the ownership of an item like the Cyrus cylinder is, as one can clearly see, extremely complex. Issues of religion, politics, nationhood, ethnicity, culture, and international diplomacy all converge here to form an inextricable mess.

While this specific example is probably the most vivid one can find in Adam Kuper’s book, others come to mind. One could mention, among others, the removal of shrunken Jivaro heads (Tsantsa) from the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Louvre holding unto a Beninese statue of the god Gu which had been created by a slave of the kingdom of Dahomey, or the more famous Benin bronzes.

The latter, which originate not from the country of Benin but from an older kingdom located in what is now Nigeria, have become somewhat emblematic of the question of repatriation. As opposed to some items whose origin is either unknown or which can be proven to have come from bona fide trade, the Benin bronzes, which were considered sacred by the local ruling family, came into European hands as spoils of war.

As talks of decolonization and reparation became more widespread towards the end of the previous decade, talks between the Nigerian authorities and various museums in the western world began to bear fruit and repatriation began in earnest. While most commentators have described this process in optimistic terms, others have raised a number of concerns, first of which being that of conservation: Kuper notes in The Museum of Other People that, in the decades since independence swept Africa, art theft has significantly increased. He mentions how various priceless items have disappeared, either likely stolen by unscrupulous museum workers, or offered to foreign dignitaries by state representatives.

The statue of the God Gu by Akati Ekplékendo. Photo from wikipedia user Ji-Elle, share through Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Kuper notes that the National Museum of Nigeria in Lagos, established in the 50s by British administrators, can hardly manage to display the collection it already owns, and that only a paltry 300 items are shown in its permanent collection. While one could dismiss his words as paternalistic, the sorry state of the museum has been acknowledged time and time again by Nigerians themselves.

Not only does the museum lack space to display its collection, there is little oversight of the items in storage, which are both prone to disappearing and suffer from degradation that comes from inadequate power supply. Another factor contributing to the museum’s shortcomings appears to be the country’s religious landscape, which is dominated by Christianity and Islam, leading some to hold ambiguous views of their country’s Polytheistic heritage:

The museum librarian, Taiye Pedro, said religion was a major cause of public apathy towards the museum. Pedro explained that many Nigerians believed that items in the museum were fetish and hence preferred to go to amusement parks and recreational centres. He said, “Religion has blindfolded us. Every individual of this jet age believes the museum contains fetish materials. When we have new workers posted here, as soon as they see what we are doing, they will want to resign. They have the presumption that to keep this collection of objects, we put oil on them and pour libations, which are not true. These misconceptions have reduced the number of people coming to the museum. (from the Nigerian journal Punch).

However, despite, or maybe because of the challenges faced by public institutions such as the National Museum of Nigeria, others avenues for repatriation have recently been devised. Starting in 2022, the Nigerian government, upon receiving two artifacts previously kept in England, handed them over to the current Oda, the traditional ruler of the Nigeria Edo people and descendant of the Beninese king who lost power following the British takeover. Nigerian authorities later clarified the situation further by stating that each and every of the looted Benin bronze that comes back to Nigeria will return in the ownership of the Oda.

By law, the Oda may therefore keep any of these artworks away from the public eye and use them to adorn his private palace, as well as sell or gift them. While a museum dedicated to the Benin kingdom is slated to open in 2024, it is therefore unsure which of the repatriated bronzes will end up being displayed within its walls. This last example illustrates once again the complexities inherent to heritage ownership, especially this time when it interacts with ideas of private property, history, and class.

Using cases such as these, Kuper manages to make a solid, if not bullet-proof case for looking at the issue of repatriation not through the lens of justice, identity, and grievances. Instead, he proposes to rethink the way one communicates and exhibits global culture in order to strengthen international and cross-disciplinary scholarly expertise, prioritize preservation, and facilitate dialog. In short, he champions a humanistic and scientific approach which he hopes will quench the flames of revanchism and deconstruction currently affecting the museum world.

If this thesis is worth arguing for, Kuper falls unfortunately short in several aspects. His near-complete dismissal of traditional religious knowledge (once dubbed “New-Age nonsense”), practices and worldview can feel somewhat distasteful for instance. He also never spends much time discussing the importance of enhancing knowledge communication by rightfully contextualizing artifacts within their own environment.

All in all, The Museum of Other People makes for a great, educated even, pamphlet which unfortunately misses the mark when it comes to truly engaging with outside perspectives.

The Wedding at Cana by Veronese. Public Domain.

When it comes to my own thoughts on the subject, I must admit that Kuper’s writings made me think differently on the practicalities and process of repatriation, but he never quite managed to wholly sway me. As far as I am concerned, I remain of the opinion that, in principle, each and every piece of looted art or artifact whose provenance cannot be properly ascertained ought to be taken back to where it originated. I would even go further: items that were acquired through legitimate means but which are of particular significance, especially for practitioners of indigenous and minority faiths, ought to become available for potential buybacks if the situation permits it.

Of course, the welfare of the artifacts themselves need to be taken into consideration. Is it necessarily a good idea to ship unique pieces of priceless heritage back when they risk being destroyed, or looted once more? Some would say that, regardless what may happen, stolen goods should be given back, no questions asked, and that any excuse not to do so reeks of paternalistic and colonialist attitudes. However, could this not, in some cases, ultimately be a detriment to the nation whose heritage was originally stolen? One could imagine a case where a radical Islamist or Charismatic Christian sect takes over a state, and then demands the returns of ancient polytheist artifacts only to desecrate and destroy them.

This, however is only an extreme example and, as we have seen earlier, the greatest threat heritage institutions face is that of a lack of funding and professionalization. Governments of countries that engaged or profited from the looting of art and religious paraphernalia should work hand in hand with representatives of the nations who were deprived from their treasures in order to establish solid foundations upon which a culture of appreciation and conservation of those artifacts may thrive.

These considerations, if they best exemplify the problematics of art theft inherent to colonial practices, can be applied domestically as well. All too often, the most iconic heritage of a nation can be found mostly within a handful of public and private institutions, almost all located in capital cities and other large urban centers. This often happens at the detriment of local museums and other establishments that would benefit immensely from being able to showcase local heritage to its local population.

After all, if the Benin Bronzes are considered to be more at home in Nigeria than in London, why should the Sutton Hoo helmet not be held in Sussex for instance? Why should Scandinavian runic stones be dislodged and taken to institutions hundreds if not thousands of kilometers away from where they once stood if there is a suitable museum to house them in? I believe that the idea that significant artworks and archeological heritage should only be displayed in massive, centrally located institutions is one of the root causes of looting in the first place.

Instead, we should start to ask the question – what is the point of showcasing these ancient artifacts? Is it to entertain people? Is it to gain glory by associating oneself with these priceless objects? Is it just to generate revenue? This way of thinking needs to be turned on its head.

Yes, in a fundamental way, we need heritage, especially spiritual heritage, because it informs us about who we are and where we are from. But this heritage also needs us. Like hallowed ancestors, heritage needs to be preserved, cherished, and celebrated just because it exists, because it is the right thing to do. Nowhere better can this process take place than where this heritage came to be.

This is why I support repatriation and hope that every nation, every tribe, and every province will one day be able to reclaim the past that is rightfully theirs and celebrate it, in whatever way they seem fit.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.