It’s the day after Christmas, the beginning of what Norwegians call romjul, the couple of days between Christmas and New Year when not everything is quite closed but most people take it easy and stay home. Here in my Arctic hometown of Tromsø, the weather is awful, with ice all over the streets, gale-force winds, and snow starting to fall. I had just managed to escape that freezing death-trap some people call “the outside” and get started with my work day at the Polar Museum.

Up until a certain infectious disease started messing everything up, I primarily occupied myself as a tourist guide, and regularly took tourists to the museum so they could learn about Norway’s longstanding tradition of polar exploration and exploitation. While the tourism industry completely collapsed in the middle of March, I was soon able to find a part-time job at the University of Tromsø Museum (of which the Polar Museum is a branch.) As the holiday season approached, I took the opportunity to take a few extra shifts, including some at the good old Polar Museum, which is located a mere few hundred meters from my home.

After turning the lights and the surveillance cameras on, I grab a microfiber cloth and a spray-bottle filled with some sort of undefined disinfecting agent and get ready to start cleaning the exhibits’ numerous touch-points. Once I am done with the diorama room depicting the time-honored tradition of baby seal clubbing, I head upstairs and enter the hall dedicated to the conqueror of the South Pole, the one and only Roald Amundsen.

In the center of the room stands a large stone bust of the explorer, which gives surprising significance to the explorer’s jagged facial features. When I was a guide, I would always come to that stony face and point out, among other things, the remarkable size of Amundsen’s nasal cavity, liberally prodding it in the process. Even if no tour guide is likely to show up today, it stands to reason that this stony snout might still see a fair bit of action today, so I chose to treat it as a touch-point.

I lightly wet my cloth and apply a think veneer of disinfectant on Amundsen’s face. At that moment, it hit me: in some way, does my rather profane act not mirror the work of Pagan priests of yore? Those who would dedicate themselves to a temple-deity and devotedly wash the hands and feet of their beloved gods and esteemed heroes?

This started its own train of thought: in today’s world, where Pagan artifacts are held by institutions that generally don’t concern themselves with matters of faith, could modern practitioners of the old religions make use of museums and other public spaces in their spiritual practice, and if so, how?

The Amundsen exhibition at the Polar Museum in Tromsø [L. Perabo]

At the branch of the museum I work at most often, Pagan religious artifacts are very rarely exposed, with the only example I can think of being a Sámi shaman drum from the early modern period. On the other hand, a whole aisle remains dedicated to local North-Norwegian church art, with objects stemming from the early Middle-Ages to the 18th century. While most of the tourists I have guided there displayed a real interest and probably identified as Christians, I cannot say that I saw anyone engaged in any kind of prayer, spiritual reflection, or any kind of religious activity.

In a way, this makes sense. For Christians, there are hundreds of thousands of churches and chapels all over the world, and it was not all that unheard of for some tourists of mine to kneel or recite a prayer when we visited some of the local churches. Why kneel on the concrete floor of a museum when there are living, breathing houses of worship aplenty? On the other side of the spiritual spectrum, so to speak, we Pagans rarely can complain about a superabundance of dedicated religious practice spaces. And while I will be the first to recognize the undeniable power the natural world holds, there is still something about an enclosed, built-up space that hits differently.

In the absence of such dedicated cultic spaces, some might turn their attention to other areas where the gods, or at least their likenesses lay: museums.

I, and I surmise most Pagans and likeminded people, really like museums. Being born in Paris, I had the chance of visiting the world’s largest museum, the Louvre, no less than half a dozen times. Every time I stepped under its massive glass pyramid, I would lose myself for hours, fill my head with representations of gods and heroes of ages past, turn my feet into mushed peas, and always have something more to discover for next time.

While the origin of the word “museum” lays in ancient Greece, the idea of the modern museum stems from the Renaissance. In this period, wealthy and inquisitive individuals would routinely collect various items – such as animal parts, sculptures, paintings, books, and other trinkets of note – to show to their peers. One of the oldest museums still in existence, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, started just like that in the 17th century, built from the private collection of antiquarian and alchemist Elias Ashmole.

When in the summer of 2019 I visited that very museum, I was pleasantly surprised by the wealth of artifacts on display: Roman coins, Greek statues, and Viking rune-stones filled each and every corner of the enormous building. But when I came up to the second or third floor, and entered a near-deserted room dedicated to Egyptian antiquities, I started feeling somewhat conflicted.

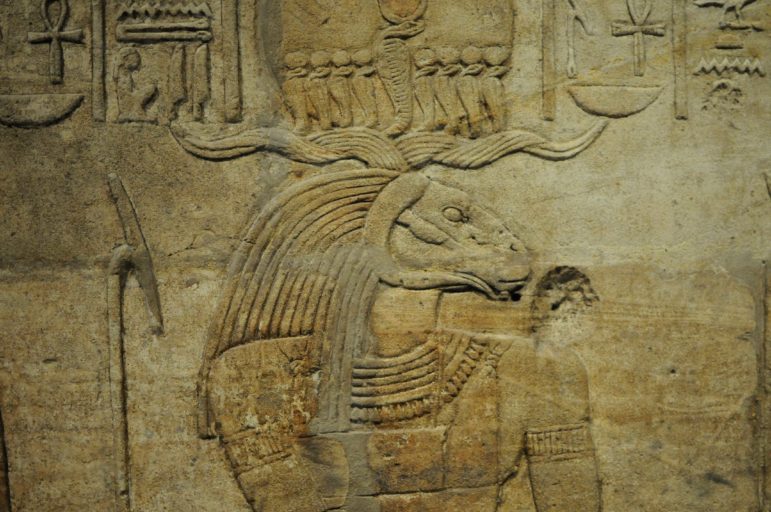

While the preservation of historical objects is one of the noblest activities there is, I could not help but feel like some of the cultic artifacts, such as the massive relief depicting the God Khnum, felt a little drab, not because of any faults of their own, but because of their immediate environment. While the face of the ram-headed god of the Nile would once have been the witness to countless rituals, processions, and other acts of faith, it had now been relegated to the corner of this murky room, where tourists might gaze at it for a second before heading to the next exhibit.

The Khnum relief at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. [L. Perabo]

Don’t get me wrong: museology is a complex matter, and no institution will ever be able to exhibit all of its artifacts in the most fitting way possible – but still, is being encased behind a glass window really the end game for the old gods? Or could there be other ways to highlight and show respect to both the objects and the deities they depict?

When I was still a kid back in southern France, I remember reading an opinion piece in the paper about the Louvre. It argued that the venerable museum, which keeps significantly more artifacts in its vaults than it actually exhibits, should distribute its riches to private citizens. Those citizens would then be able to loan and exhibit one item in their home. This, claimed the author, would make art and history significantly more accessible to the general population, and help foster a sense of respect and national pride among those who would thus become wards of the nation’s treasures.

While this proposal would, in practice, be near impossible to implement, the author of that piece did hit a nerve: maybe there would be individuals, organizations, communities, and so on, who would value, care for, and promote artifacts that would otherwise be left gathering dust in a warehouse instead. We have been seeing something along those lines in the past couple of years, with the debate on the eventual repatriation of artifacts taken to the West from colonized nations in the 19th and 20th centuries.

While this topic remains fraught with controversy, there have been a number of cases in the past few decades when cultural, and even at times cultic, artifacts have been handed back to their nations of origin. In some cases, ceremonial items that had spent decades under literal lock and key have revitalized traditional religious practice, such as with the Blackfoot spiritual societies of southern Canada.

A similar reasoning could also be applied for local, as opposed to national institutions. How many times have curators of large museums come over to the isolated countryside following the discovery of a significant archeological find, only to pick the site dry and display it hundreds of kilometers away in the capital city? How powerful would it be to keep sacral artifacts near the sites of their discovery, contextualizing their presence in the landscape and through the people who made them?

While there are valid arguments against keeping archeological objects in smaller and less centralized institutions, such as the increased risk of theft and deterioration these items would face, it could be said that the pros could well outweigh the cons.

Even if this is probably nothing but idealistic wishful-thinking, how powerful would it be if Pagan groups were able to do just that, and become the caretakers for ancient sacred relics? To take in, even temporarily, votive stones, cultic tools, and representations of their cherished gods and goddesses? What kind of sanctuaries could one dream of building around, for example, just a small oxidized Thor’s hammer, or a genuine Matronae relief?

One could also consider whether Pagan spiritual societies could make use of sacred spaces such as burial mounds or temple ruins in a way that would also benefit both the heritage institutions and the general public.

If there is one thing I have learned from half a year working at this museum, it is how hungry both the public and the workers are for engagement. Before I started selling tickets and making waffles at the museum counter, I would never have imagined how much children love the place, and how many of them can be found zooming through the various exhibits at any given time. I also never realized how hard the staff worked to find new ways to make known the vast trove of knowledge and items kept at their disposal.

When I started here, my coordinator told me that, for the past couple of years, the old church art exhibition had even been used to stage actual religious services in cooperation with the Church of Norway. While I was not able to witness this event last year due to the aforementioned infectious disease, it made me think – what if I proposed we did something similar, but for the old religion instead? Maybe we could take the old gold-plated sacral axes, and even our little runestone out of storage in time for the next Midwinterblót?

Who knows how it would go – but be certain, I will report back if it ever happens.

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.