Every Monday I set out offerings for the household. Time is a premium for me, so it’s one of the few times during the week that I’ll bake or cook as the mood takes me. What I make depends on a few things – what I have on hand, how much time I can spare, and the intuitive sense of requests that I get from the spirits in the household.

Intuition is one of the least solid ways I have to communicate with the spirits, but it’s also one of the clearest and the easiest to discern. Case in point: last week, when I was making oatmeal for the house spirit and the ancestors, my husband was in the mood for something altogether less wholesome.

“This,” I said, pouring hot sauce over the oats, “is disgusting.” The smell still wasn’t quite right – I followed the sauce with butter, rosemary, and, somewhat horribly, butterscotch chips. “Can we be done?” I asked, looking at the concoction with dismay, and then went to fetch the whiskey from the cabinet.

When completed, the bowl looked like a crime scene, both overly-congealed and runny, the spicy-sweet smell of it hounding me out of the altar room and down the hall. “He did it again,” I complained to another partner, cracking a window to let in the Chicago spring air. “It’s every week, like this.”

“I think he’d stop, if you asked him,” my partner said, amused. “But then how would you know he cares?”

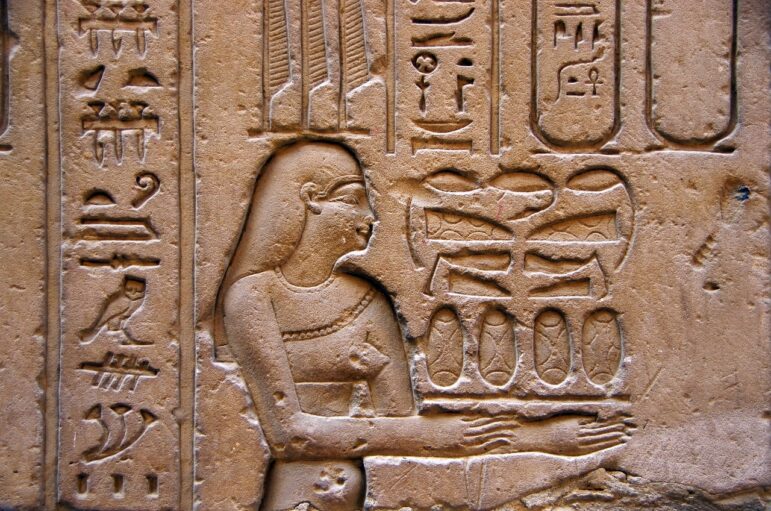

An ancient Egyptian carving showing loaves of bread [Pixabay]

He’s not the only one with dubious tastes. One of the first pieces of Pagan Drama™ that I ever heard was the saga of Spongecakegate. For the uninitiated, in September 2012, someone on tumblr mentioned that, in their experience, Loki enjoyed offerings of cheap pre-packaged sponge cake. Someone else responded, essentially, that sponge cake wasn’t an historically accurate offering and was inappropriate. Things spiraled from there, with dozens of people piling onto the argument to the point that many people of a certain age who work with Loki acknowledge the fourth of September as a tremendously silly, tongue-in-cheek holiday.

I first learned about the whole mess from a series of memes, months after the original overblown event. The idea of an “appropriate” offering, based on historical precedent or best guesses, was familiar to me, but in a community like the Lokeans, with so little information about historical cultus, focusing on historical precedent was unlikely enough that it had become a joke, completely divorced from the vibrant, living modern practice. The underlying ethos of the conversation formed my approach to Paganism itself. I learned it was important to draw from the resources I had. And when those failed? Well. It was alright to share things that I loved from my own life, to trust my instincts, to be a little silly as I fostered my spiritual relationships.

My altars were the clearest places where this approach shone through. Freyr got an antler, a series of carved runes, an acorn – and a little plastic pig, rescued from the floor of a friend’s car. The space I had set aside for Thor gathered a series of stones, a hand-forged hammer, a piece of lightning struck oak – and a red straw julbok, a gift from a friend that never made it back into storage after Yule. My room became a Wunderkammer of sorts, filled with strange and magical items right alongside cheap pieces of mass-produced plastic that made me laugh and reminded me of my friends. The ways in which I saw the gods grew into a visual language, a series of physical metaphors grounded in my everyday experience and sprawling across my living space.

Like all languages, it began to create its own meaning.

As with everything about my spiritual life, there’s a level of chicken-or-the-egg to this. Are the patterns I notice, the stories that grow out of my altars and offerings, reflective of my own biases and humor? Or are they reflective of some deeper truth about the spirits, as individual as their wildly varied preferences? I’m aware, however distantly, of the circumstances that have allowed Ancient Greek and Roman representations to pass down the centuries into modern culture. There are reasons that the record is so clear, and that the images associated with the gods are both uniform and largely unchanged. Is this why my altar for Hermes is laden with statues, pictures, and medallions of his face? Or is he, perhaps, just fond of seeing himself represented? Did he have a hand in making sure that he’s recognizable enough for me to know him in museums, on train stations, on the sides of vans? Just as likely: do I simply like looking at him?

This is the sort of question that can spin me up, weigh me down with theology, and keep me from actually doing anything about my spiritual life. Thinking about it for too long, with too much seriousness, makes me self-conscious in a dozen different ways. I’m aware of the classist, capitalist roots of my own acquisitive nature. I don’t want to centralize items in a way that makes my privilege and access to money key to my relationships with my spirits. I worry that I am taking things too seriously and, equally, that I am being ridiculous, creating panoramas out of nothing but my own greed. If I am stressed and defensive about the things I have that remind me of Farbauti (a card from a divination deck, a statue from God of War, and a pair of Marx brothers glasses), it’s harder for me to feel good about reaching out to him. If I am busy questioning the impulse purchase of a rock and why it feels right for my working altar, I’ll lose time I could be spending on actual spells. Altars open up space for contemplation – and contemplation is, for me, sometimes exactly what silences my intuition.

Offerings are different. The kind I offer – food, drink, incense – are transitory by nature, which limits the amount of thought that I can put into them. If I make something that doesn’t feel quite right, then it’s only a few days before I’ll make something else. They’re also, in my practice, specific to the time and place in which I live. I know enough about the gods I work with to know that some of the offerings they’ve received in the past are well outside my ability and interest to offer, which means that I think a lot about their modern parallels. I’m no farmer, and don’t have any livestock, but I have time, food, and energy. My neighbors might object to processions with a tambor and whistle, but I can play music, sing, pray with fervor in the ways that feel right to me.

By all rights, the limitations that make me focus on my own situation should make it so that all the offerings I make are similar. If I open the cabinets on a Monday and have only one option for my offerings, then my own tastes should dictate what a “good” version might be. So it’s doubly surprising when I get a sense that no, actually, cranberries and butter are not the best choice for a house offering this week. It leaves me confused, staring at the cabinet and waiting for inspiration to strike, something else to suggest itself as a better option.

These moments are as close as I can come to being unselfconscious, these quiet times of listening and intuitive action. When patterns become clear it’s only after the fact, after weeks or months of a spirit requesting a certain taste, a certain scent, after I have reached in blindly and pulled out the same canister or box of incense time and time again. And it’s harder to question whether I’m the one imposing my own tastes when I’m halfway through making something that seems, even with all of my fondness, like a crime against the concept of food.

This is how I’ve come to the conclusion that Hermes likes savory, herbal tastes – anise, dill, and fried meat. This is why I separate out the butter into salted and unsalted piles before serving up baked goods to different areas of the house, pausing for a moment to see where, exactly, each plate should go. This is also why it strikes so surprisingly, and so intensely, when I hear an echo of these unthinking patterns from someone else.

Drinks with friends [Pixabay]

It isn’t proof. My understanding is that spirituality is a different kind of truth than science, and the details that lead up to my conclusions will always be circumstantial, always limited to the shifting world of interpretation and conjecture. There is no such thing as fact, in religious practice. The closest I can come is when something I believe, something I have built out of my own interpretations and relationships, shows up somewhere else unexpectedly.

The closest it comes to feeling like fact is when the corroboration comes from the past. Picking up a new book and learning that the ancient Greeks burned animal fats for the gods can give me a new take on Hermes’s KFC addiction. But what hits home, what makes me feel like I am speaking to someone real, is when a stranger shares my experience.

“He wants ouzo, on the rocks,” my friend tells me as we unload for a ritual. “Took me years to figure out. It gets all cloudy when it pours, and he loves it.”

“I can’t stand it, can you?” I ask, and pull out the bottle from my bag. He looks at it and grins at me, both of us surprised and sure, beyond a doubt, that we know the same person, that we know someone real.

“Never touch the stuff,” he says, and pulls his own bottle out. “You have any ice?”

These are the ways I talk to the spirits: intuition and synchronicity, coincidence and pattern. These are the ways I know that they listen.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.