. . . I should like my life to be like an abundant river, flowing over the land with joy.

(Amedeo Modigliani,1901 letter from Capri to Oscar Ghiglia)

Everything begins with a story. How we met our partner, the times into which we are born, the so-called history of any people or nation, the myths by which we attempt to impose meaning on existence. This story is about a land far away from me, but which has reached out to me for many years with the most gentle persistence. Ancient Egypt became the existential frame around which I configured my personal theology, very gradually, and over many years.

Author on a water taxi near Valley of the Kings [Courtesy]

In November 2022 I finally was able to make my pilgrimage to the famed land, following in the footsteps of tourists going back at least to classical antiquity. My use of the word pilgrimage is very intentional. This was no vacation, although I was completely removed from home, family, and work during that time. It proved, in fact, to be the most physically demanding experience of my life. The challenges of sleep deprivation, a serious early fall, and the rigor of keeping up with our tour guide (even though my husband and I were not part of a group) all contributed to my sense that this was a sort of initiatory journey and the rigors accompanying initiation.

That’s only a hint of my own account; the real tale is the traces and memories that I found everywhere I looked in Egypt (between Cairo and Aswan, from Giza to Philae). The ancients apprehended story in every part of their world, and fortunately for us, they were compelled to record, or at least encode, these narratives of meaning on every available surface, and even the shape of the land itself. Appropriately, they honored several deities identified with processes essential to storytelling.

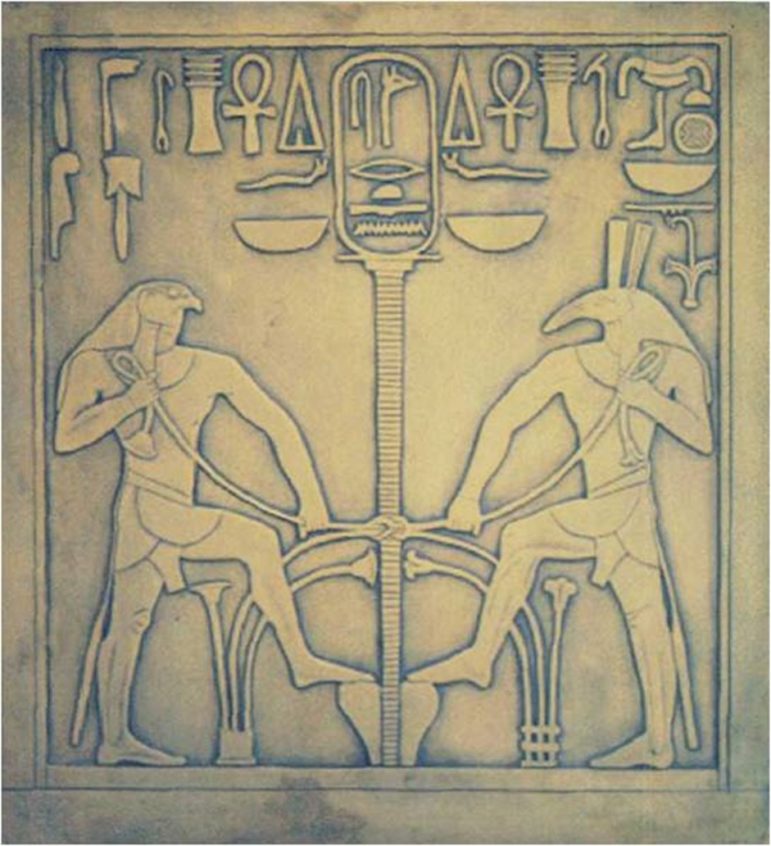

Horus and Set uniting the Two Lands [Courtesy]

Ptah (the P is pronounced, unlike the far later Ptolemies, who were Greek) is a creator god whose Memphite Theology describes creating with his tongue, through the power of speech. Parts of the Memphite Theology are so similar to the opening of the Gospel of John in the Christian Bible that the latter is assumed to be derivative of the former. The cult center for Ptah and his consort Sekhmet was at Memphis, one of the most important ancient capitals, but the veneration of Ptah was widespread.

Djehuti, also known as Thoth (a later Greek appellation) is the great divine scribe who records the results of each person’s afterlife judgment and plays several other key roles in ancient mythology. The god with the head of an ibis turns up in virtually every Egyptian temple and was a key advisor for both gods and kings. He was said to have invented writing, and so we honor him as guardian of Egyptian lore long assumed to be secret (before we could read hieroglyphs).

But most of Egypt’s stories do not involve speech or writing; they are written, so to speak, in the land itself. No doubt nb TAwj, (b) the Two Lands, imprinted their lore on the hearts of the ancients, for the Egyptians considered the heart to be the seat of thinking, conscience, and emotion. Their written record contains countless references to the joys of living in Kmt, the desire to always return there and to be buried in the home of their hearts. There is no doubt that my own heart now carries that imprint for Egypt feels like my other home.

The defining characteristic of Egypt, both ancient and contemporary, is the gigantic silver serpent that begins far to the south in Nubia – the Nile River. Although prehistoric Egypt was an abundant savannah, by the time of our story it had become a rocky desert, blown with sand, save for the life-giving stream of water embodied in the god Hapy. Because of the Nile, Egyptians enjoyed a prosperity unrivaled in antiquity. Most years they exported grain to the rest of the Mediterranean world. The Nile was how one normally traveled—to the west bank to visit tombs of the ancestors, to attend a large festival like Opet or the Beautiful Feast, or to transport goods. And because of a shallow water table, the countryside for about a mile to either side of the river is green and blooming, a veritable long oasis.

Moon over the Winter Palace gardens [Courtesy]

This river most definitely flowed over the land with joy, flooding each year until the Aswan Dam was built in the 1960s. The flood brought rich black topsoil down from the African highlands, providing natural fertilizer for crops. Even though there is no longer an annual inundation, during my trip I saw lush evidence of the role agriculture continues to play, being about one-eight of the economy. I also observed that most of this is still farmed by hand by people and families who live nearby. Everywhere donkeys trotted their people passengers and carried donkey-sized loads of sugar cane, river grass or market vegetables. About a fourth of Egyptians are employed in some aspect of agriculture, just as their ancestors have been for more generations–indeed, more centuries–than anyone can remember.

No wonder, then, that we find depictions of the god Geb as the earth, painted with plants erupting all over his reclining body. Or worship of Osiris as not just a god of the afterlife, but a living example of the never-ending cycle of growing things, and of the ability to resurrect, doing so daily, renewed by the sun.

The river became a motif repeated in countless tomb and temple paintings and papyri afterlife books. The Milky Way was seen as a mirror of the Nile (sometimes referred to as the “starry Duat”). Most tomb stela are inscribed with the deceased’s declaration that “I ferried the boatless,” along with claims to have fed the hungry and clothed the naked. Even the gods traveled by boat (also called by the later French term, “barque”), and many temples have special rooms for housing a god’s sacred barque when it is not in use, or when one deity is visiting the temple of another, like Horus and Hathor. The dead traveled through the Duat, the afterlife, in a barque, reenacting the nightly journey of Osiris. A boat became a ubiquitous symbol of one’s ability to change, to continue living, to cross boundaries, and to surmount the difficulties posed by distance.

Much has been said about the worship of the sun by the ancients, and it is most definitely an icon inseparable from the entire landscape. For nearly two weeks I saw only blue sky before coming home to the great winter storm moving across the United States in December. Because we did not travel during the brutal summer, our experience of the sun was beneficent, much like the Heretic Akhenaten must have celebrated. Even though I dislike Amarna period art, did not visit there, and find Akhenaten himself repugnant, I confess that there were a few times it seemed I was being caressed by those little hands at the end of each sun ray. Long before his heresy, though, the Egyptians understood the sun to be the one thing in their world which was entirely predictable and constant. This sun, together with the land and the river, provided the essential ingredients for life, whether successful growing of crops or plentiful hunting and fishing.

We also enjoyed the most beautiful moonrise each evening during our stay at the famed Winter Palace hotel in Luxor. Djehuti was considered a lunar deity, and on my return, I watched that same moon over South Carolina with a fresh understanding of its passing over my other home seven hours before. There is the same feeling about the sun; it shines through a much different pattern of weather in North America, but it is constant and unwaning, continually and forever as the ancients would have said, NHH and Dt.

Agriculture by the Nile – western mountains in background [Courtesy]

There is no end to the stories heard and seen during my pilgrimage. But most importantly, I returned changed, as one should following an initiation. Everything I have studied for the past two and a half decades moved in a flash from the abstract and academic to a new place in my personal reality. In the same way that Horus and Set draw tight the cords which bind the Two Lands, I felt those cords pull together for me as our return flight landed in New York. I am now bound to a second homeland, Kmt.

Before I left, a good friend encouraged me to refresh my connections with my own deities during the trip so that I could bring them home and make them truly of this land where I live, too. This may once have sounded like pretty words. And it somewhat challenges the West’s progress in recent years of recognizing and avoiding cultural appropriation. We Pagans say we are people of the land and should find who are the spirits of our own place. But as moderns, we have dispersed far and wide around the globe. In spite of these apparent possible contradictions, there is no question that I and Egypt are powerfully connected in a way that defies explanation.

I never thought I’d be able to make this trip, for financial reasons. When the opportunity presented itself, I knew it was a carpe diem kind of moment. I have often pondered the phenomenon of my own inexorable attraction to ancient Egyptian spirituality. Furthermore, I could never seem to escape this feeling of familiarity with ancient Egypt that would not go away. I cannot say post-travel that I now feel closer to my gods; it’s more like the feeling one has after a good visit back home. Bonds are renewed, expectations are clarified, and new understandings surface. Whatever the logic of my connection, I have chosen to honor it in my own way, founding a tradition we call Osireion (another story for another day).

I am not an ancient Egyptian, though my DNA says I have ancestors who travel from Nubia, up through Kmt, and beyond. I was born an ocean and continent away in a completely different time and culture. For this pilgrimage, I am grateful beyond words. Now I will spend my remaining years doing what I can to share that connection with others whose journey may not include a physical visit. Even in my own time, it seems I am destined, like the opulently abundant Nile, to flow over the land with joy.

Holli S. Emore, MDiv, is Executive Director of Cherry Hill Seminary, founder of Temple Osireion, and author of Constellated Ministry: A Guide for Those Serving Today’s Pagans (Equinox, 2021).

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.