The skies over Chicago today are not the same as the skies over the ancient northern world.

In the heady days of the long-ago time, Anglo-Saxon chroniclers could report “fierce, foreboding omens” that warned of the coming of the first Viking raids and write of “excessive whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons [that] were seen flying in the sky.”

Despite the multivalent looming dooms that we now face, we don’t see dragons when we look up at night. We often don’t even see stars.

“State Street by Night, Chicago, Ill.” postcard illustration (1909) [Public Domain]

Since I was a child, there have been nights when I sought the stars floating in inky blackness and instead saw the bright orange glow of the Windy City’s electric lights obliterate the celestial bodies and replace darkness with a weird half-light reflected from sky-spanning cloud cover.

On nights when the skies are clear and some of the stars can actually be seen, I have often wondered what star or planet a particularly bright dot in the sky is, only to realize from its movement that it’s a high-flying passenger plane.

This compromised sky of ours is just one of the many challenges facing those of us who practice Ásatrú and Heathenry – new religious movements inspired by old Norse and Germanic pagan religions – while living in urban settings.

Norse mythology tells us that the gods made the sky from the skull of the primeval giant Ymir and raised it over the earth. It’s difficult to recapture a mythic sense of mystic awe when looking up at a sky crowded with big old jet airliners hovering over O’Hare and waiting to carry people far away, flying faster than the swiftest Viking ship and belching more smog than any dyspeptic dragon.

How can city-dwelling Heathens bring back the old sense of wonder when gazing upwards? How can we reenchant the post-post-postmodern skies in this third decade of the 21st century?

Through hardships to the stars

To begin, we can accept that we aren’t alone in not always being able to see the stars. Long before this age of air pollution and light pollution, there were cloudy nights, of course. Just as we sense the presence of divinity without physically seeing it, we can sense the stars above when they are invisible to us.

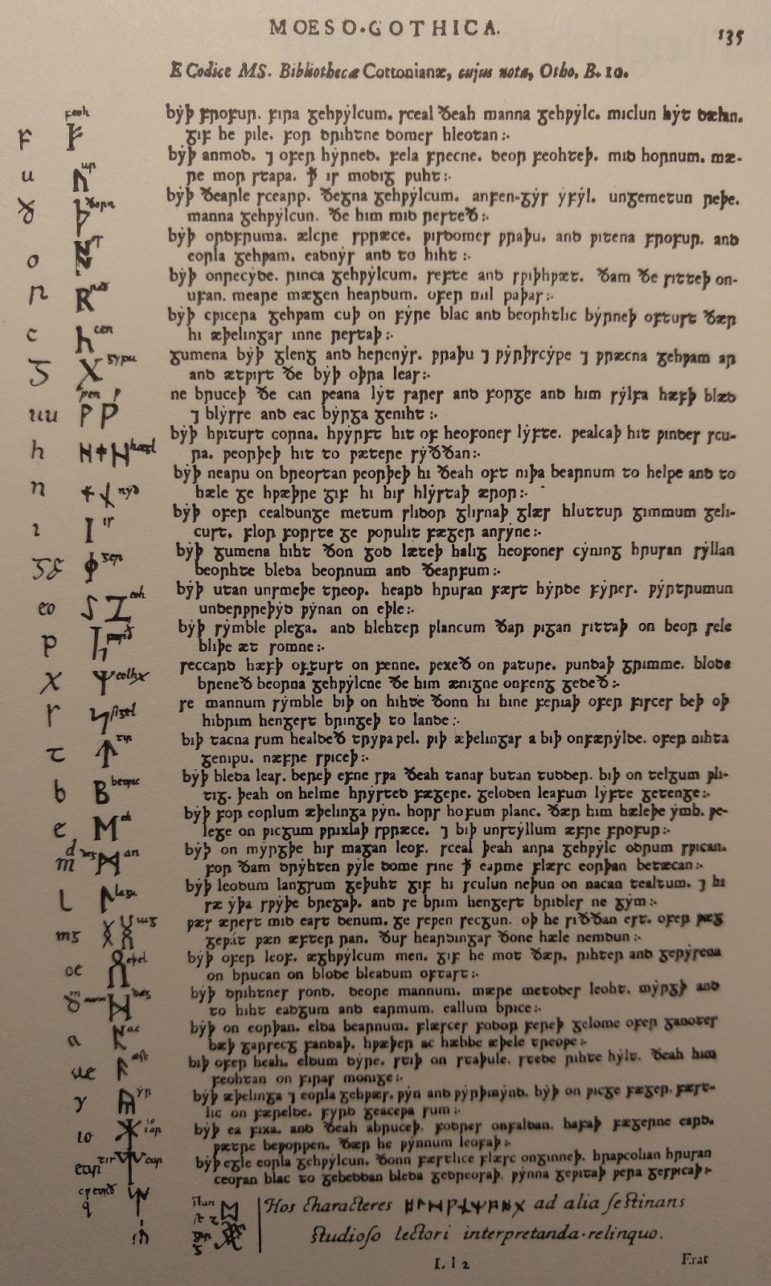

The 9th- or 10th-century Old English runic poem, which provides 29 futhorc runes with defining verses, has this to say about the Tir (Old Norse Týr) rune:

T. is a guiding star; well does it keep faith with princes; it is ever on its course over the mists of night and never fails.

Even when we can’t see it through the mists that cloud our vision, the star associated with the god who gave his right hand to bind the enormous beast Fenrir is there to faithfully and unfailingly guide us through the darkness of night. Such a symbol of dedication and guidance is felt with the heart more than seen with the eyes, in any case.

Perhaps the Tir/Týr rune, which looks like an arrow pointing up, is guiding our gaze up to the North Star, that constant guide for travelers from time immemorial and a fitting starting place for sidereal re-enchantment. The rune invites us to look up to the skies and see, with both our outer and inner vision.

The Old English runic poem as it appeared in the first printed edition of 1705 [Public Domain]

Another single star singled out in the Norse myths is Aurvandilstá (“Aurvandil’s toe”). In his Edda of c. 1220, the Icelander Snorri Sturluson tells of Thor carrying his companion Aurvandil in a basket while crossing a river on his return from Jötunheim (“giant world”). Aurvandil’s toe sticks out of the basket and is frostbitten, so Thor breaks it off and sets it in the sky as a star.

The Old English equivalent of the name Aurvandil is Earendel, which J.R.R. Tolkien discusses in a letter draft of August 1967, writing of “the obviously related forms in other Germanic languages”:

it at least seems certain that it belonged to astronomical-myth, and was the name of a star or star-group. To my mind the [Old English] uses seem plainly to indicate that it was a star presaging the dawn (at any rate in English tradition): that is what we now call Venus: the morning-star as it may be seen shining brilliantly in the dawn, before the actual rising of the Sun.

Here is a second empyrean point for our re-enchantment project. The planet named for the Roman goddess Venus, identified with the Norse Frigg already in Germanic pagan times, serves as both the evening and morning “star” – the first bright celestial body to appear as the night begins and the last to wink out as it ends. Whether we associate it with Odin’s wife or Thor’s friend, it can be a symbol of companionship and comfort in dark times.

In the Old Norse mythological poem Hárbarðsljóð (“Graybeard’s song”), Thor brags of placing other stars in the sky. In Carolyne Larrington’s translation, he says:

I killed Thiazi, the powerful-minded giant,

I threw up the eyes of Allvaldi’s son

into the bright heaven;

they are the greatest sign of my deeds,

those which since all men can see.

Snorri Sturluson gives credit to Odin for transforming the eyes, writing (in Anthony Faulkes’ translation) that he “threw them up into the sky and out of them made two stars” as compensation given to the giant’s daughter Skadi for the killing of her father by the gods and as part of her welcome into the divine community.

A logical astral choice for the giant’s eyes is the pair known as Castor and Pollux, which are part of the Gemini constellation. Castor (actually a system of six stars appearing to us as a unity) and Pollux shine brightly together from the sky, and it’s not difficult to imagine them as enormous eyes looking down on us.

Whether as a sign of Thor’s protective might or a testament to the value of resolving disputes and welcoming the “other” into our communities, these shining stars return our gaze.

Wheel in the sky keeps on turnin’

As a little kid, my favorite constellation was the Big Dipper, mostly because it was the one I could always find in the sky above the city. As a white-bearded old wizard, the same constellation is still my favorite, since it has such a wonderful connection to the thunder-rider.

In an often copied but seldom cited passage in Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (1899), Richard Hinckley Allen writes of the Big Dipper:

The Danes, Swedes, and Icelanders knew it as Stori Vagn, the Great Wagon, and as Karls Vagn; Karl being Thor, their greatest god, of whom the old Swedish Rhyme Chronicle, describing the statues in the church at Upsala, says:

The God Thor was the highest of them;

He sat naked as a child,

Seven stars in his hand and Charles’s Wain.

Aside from my obvious affinity for both my favorite constellation and my own first name being associated with Thor, there are suggestive elements here that continue to give me a thrill whenever I explain them in my courses on Norse mythology and religion.

The seven stars of the Big Dipper (also known as Ursa Major, the Great Bear) are indeed easy to see as making up Thor’s Wain, his wagon. In the first volume of Jacob Grimm’s monumental Deutsche Mythologie (1835, published in English as Teutonic Mythology, 1880), a source cited by Allen in his book on star names, the German philologist and folklorist writes

We know that in the very earliest ages the seven stars forming the Bear in the northern sky were thought of as a four-wheeled waggon, its pole being formed by the three stars that hang downwards.

The handle of the Dipper can be seen as the wagon-pole connected to Thor’s goats, and the cup can be seen as the wagon in which Thor himself stands. Then things get really interesting.

If we draw a line up from the two stars that make the back of the wagon, they lead to the handle of the Little Dipper. If we imagine Thor standing in the wagon, stretching up his arm, and reaching up over his head, we can see that he would be able to hold that handle.

Thor, of course, isn’t known for holding a spoon. Connecting the dots of the Little Dipper, the constellation can easily be seen as a hammer with head and handle. The bit of the Rhyme Chronicle cited by Allen that mentions the wagon of Charles (i.e. Karl, Thor) also mentions the “seven stars in his hand.” The Little Dipper – or the hammer Mjölnir, held in Thor’s hand – also has seven stars. But it gets better.

That line that we drew from the back of the wagon actually points directly to Polaris, the North Star. When we take a time-lapse photo of the night sky, Polaris appears to stay still while all the other stars move around it. In terms of Thor’s Wagon and Mjölnir, this means that the hammer spins around in a circle above the god’s head as he rides around the sky.

Thor illustration by Ludwig Pietsch (1865) [Public Domain]

Sweet Christmas! Were Stan Lee and Jack Kirby actually reflecting ancient cosmology when they first portrayed Marvel’s blond Thor spinning his hammer before throwing it?

I also wonder if the idea of Mjölnir’s handle being too short – a concept recorded by both the Icelander Snorri Sturluson and the Dane Saxo Grammaticus – is related to the length of the hammer’s handle in the constellation.

In any case, it does my Heathen soul much good to look up when the skies are clear and see Thor up there, driving his goats, and swinging his hammer. It’s a bonus that he also shows us how to find that faithful guide, the North Star.

Stargazer

It would be a fair objection to question Allen, Grimm, and other 19th-century authors as primary sources for old Germanic conceptions of sky and stars. Sometimes, the old scholars seem to know far more than we do about obscure sources. Sometimes, they clearly spin complex theories from what we would now consider very flimsy evidence.

In the face of that objection, I would gladly confess my own fondness for the idea of the Northern Lights as Valkyries riding their flying horses across the sky.

As deep as I’ve been able to dig, it seems that the origin of this common conception is in Bulfinch’s Mythology (1867) by Thomas Bulfinch. Actually, his claims first appear in The Age of Fable; or Beauties of Mythology (1855). In his section on “The Valkyrior,” he writes:

The Valkyrior are [Odin’s] messengers, and their name means “Choosers of the slain.” When they ride forth on their errand, their armor sheds a strange flickering light, which flashes up over the northern skies, making what men call the “Aurora Borealis,” or “Northern Lights.”

A footnote, rather than citing any source, states that “Gray’s ode, The Fatal Sisters, is founded on this superstition.”

Thomas Gray’s English poem (written 1761, published 1768) is based on a Latin translation of Darraðarljóð (“Spear-fighter’s song”), an Old Norse poem sung by Valkyries as they weave at a loom with men’s entrails, heads, arrow, and sword. Possibly written shortly after the Irish vs. Viking Battle of Clontarf in 1014, it is preserved within the 13th-century Icelandic Njáls saga.

In neither the English rewrite nor the Norse original is there anything that can be reasonably interpreted as referring to the Northern Lights. Maybe the footnote connected to Bulfinch’s paragraph-ending asterisk means the Valkyrie legends in general when he states that Allen’s poem “is founded on this superstition.”

If the oldest source we ourselves can find for a supposedly ancient Germanic or Viking Age conception of the cosmos above is from the 19th century, does that mean modern Heathens should simply throw it out?

One answer is provided by Norwegian philologist Eldar Heide in his article “Contradictory cosmology in old norse myth and religion – but still a system?” (2014), when he writes of the mythological associations of another constellation:

Friggerocken, literally ‘Frigg’s distaff’, the name of the constellation Orion’s belt in Swedish folk tradition, also implies that the gods may be located in the heavens: the name suggests that Frigg was imagined to be sitting up there spinning. As far as I am aware, the name Friggerocken is not attested before the 19th century, but it ought to stem from pre-Christian times, as it is difficult to imagine why Christians would invent such a name. Instead one would expect Marirocken, which is in fact attested, but likely to be a younger variant, as there are many examples of Maria substituting pre-Christan mythological women’s names.

Late attestation in the surviving written record does not necessarily mean a recent invention. Surely, in addition to the thinly stretched theories of some 19th-century authors, there are also 19th-century fabrications based on the then-resurgent popularity of Norse mythology and Germanic legend. Yet there are also amazing anthologies of folklore and works of brilliant scholarship that show incredible erudition and insight.

Where do we draw the line? If we cannot prove the prime origin of a concept without a doubt, do we necessarily need to reject it?

None of our written sources – aside from short inscriptions – were written down by the hands of ancient pagans. The 13th-century (and therefore post-conversion) Eddas and sagas of Iceland that are regularly mined by practitioners of Ásatrú and Heathenry for nuggets of religious beliefs and practices show the same sort of theorizing and tinkering as the 19th-century sources do, with their closer relationship to oral tradition perhaps canceled out by their lack of the deeper and wider scholarly knowledge that skyrocketed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

I’m not so ready to throw out everything that we can’t date to pre-Christian times with absolute certainty. This doesn’t mean I’m going to blindly accept everything that waves a raven flag in the Romantic Era.

Some American Heathens of the older generation go so far in their embrace of 19th-century Viking-ism as to embrace the saga-inspired and politics-drenched operas of the raving anti-Semite Richard Wagner as key roots of modern Heathenry that made “people aware of a spiritual power very different from the faith they knew.” That’s not a path I can follow.

What I am fully willing to do is look up to the skies and see Thor forever riding his wagon and spinning his hammer, to let the Evening Star remind me of friendship that crosses social boundaries, and to follow the pointing Týr rune and remember that, even on the cloudiest nights, there is a guiding star above that – like Týr himself – shows us the right way to go.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.