At the very end of this past summer break, immediately before the beginning of fall semester teaching, I slipped away for a tiny vacation in a little cabin on a small lake in the Wisconsin Northwoods.

I’ve been up there many times since I was very young, spending time walking in the woods and tootling around the lakes in a rented fishing boat with an outboard putt-putt motor.

During this most recent stay, I thought a lot about how deeply the stories we hear, the stories we read, and the stories we live color our experiences of being in the world.

Illustration by Jennie Harbour for “Little Red Riding Hood” (1921) [Public Domain]

The Forest

My mom has some aged photos of me around age four, taken in the golden light of late summer afternoon and faded to the reddish overglow that now somehow hovers over even my memories of the 1970s. In the pictures, I’m not yet in kindergarten, and – with feathery blond hair, clutching a baggie of golden raisins and a toy Volkswagen Beetle, and dressed in corduroys, striped t-shirt, and red zip-up hoodie – I look like a kiddie cast member from an early season of Sesame Street.

My dad took those photos while we hiked through the Wisconsin woods, when the world seemed small and safe and an afternoon was an eternity. I vividly remember the end of that particular hike, after my preschool energy had burned itself out and my flat feet were hurting. There was still a way to go to finish the meandering trail and get back to the car, so my dad started telling stories to keep me going.

I mostly remember him telling me about the dwarf Rumpelstiltskin and the clever girl who outwitted his plotting, but I know that I asked him for another story and another after that. By telling a continuous stream of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, he helped my curiosity to know “and then what happened” overpower my tiredness.

Ever since then, across six decades, I’ve associated the forest – any forest – with dwarfs, elves, secrets, songs, trolls, traps, witches, wizards, and other mysterious manifestations. All unknowingly, my ex-monk philosophy professor father was laying the tracks for my later embrace of Norse mythology and Ásatrú religion.

Maybe it’s these sorts of associations that led me and so many others to experience that particularly Heathen form of arriving at a religion – not converting, per se, but coming across the myths and the traditions (old and new) and realizing this is what I have always been, and now I have a name and framework.

Walking through the Northwoods just a few days ago, I was thinking about all of this – about story and memory and association and religion – when a pale shape off a way between the trees caught my eye. When I stopped and quietly watched, the shape resolved into the form of a white deer. Not a deer with some white on it, but a deer that was nothing but shining white.

I teach about the tale tradition of white deer in my course on the mythic sources of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, and I suppose I’ve always considered those mystical objects of the fairy hunt to be mythical creatures. Looking at that beautiful being as it looked back at me felt like a special moment, like interacting with a snippet of older folklore come to life. It gave a little bit of the bellows to that tiny spark deep inside that still hopes there’s magic out in the woods.

The local man whose family has owned the little cabin since his great-grandfather built it long ago was completely unimpressed when I told him what I saw and simply said, “Yeah, he was wandering around here a while ago,” which really underscored the need for bookish city folk to get out of town more often.

The Fire

Those who truly love books understand that reading enables us to experience other lives, both historical and imaginary. I’ve always felt that, through reading, I’ve extended the subjective length of my own life by inhaling the condensed lives that play out on paper.

Sometimes it’s single scenes that lodge in the memory and become part of our how we see the world. Sitting by the nighttime campfire I built out in front of the cabin, I felt yet again that I can’t watch curling wood or pipe smoke rise into the evening air without being taken back to the “unexpected party” in the first chapter of The Hobbit.

Illustration by Jennie Harbour for “Hansel and Gretel” (1921) [Public Domain]

That magical scene of the wizard blowing smoke rings in front of the fire really struck me as mystical when I first read it, long before I know what the word mystical meant. At this point in my life, I have that same feeling during our celebrations of midwinter, when the house is dark but for the candles, when we eat and drink while talking of memories both joyous and melancholy. Again, it was story that set the path toward later religious practice.

Tolkien called his Gandalf an “Odinic wanderer,” yet the devoutly Catholic author would surely have been displeased to learn how many modern Heathens took their first steps towards neo-paganism by following the adventures of his wise wizard.

Does it matter what Tolkien – who died just as the Ásatrúarfélagið was performing the first public Pagan rituals in Iceland in nearly a thousand years – would have thought of Ásatrú? Does it matter what the Grimms – dedicated Lutherans who collected fairy tales as part of their wider academic project on Germanic religion – would have thought of it?

I say no. The art, if it is strong, survives the artist. I do not at all believe that Tolkien, the Grimms, or even the Icelandic antiquarian and Edda-compiler Snorri Sturluson were some sort of secret pagans. I do believe that they were all lovers of the same wide cauldron of story, and those of us who love those stories today owe each of them an enormous debt of gratitude.

We do not, however, owe any allegiance to their religious beliefs. By passing along the stories in the various forms that they did, they helped those stories to have lives of their own – literary lives that can intersect with and deeply affect our human lives. The feelings that we have when reading the tales and the colored perceptions that they then bring to our experiences are our own, perhaps most strongly when they connect to what we experience as spiritual.

The Island

It’s not only the stories we hear and read early on that can profoundly affect how we see the world. I came to kung fu much later than I came to the Grimms, Tolkien, and Snorri. German fairy tales and Chinese martial arts made their presences felt at opposite ends of my life (so far), but we can still undergo major changes after our beard hairs have turned from brown to gray to white.

Since I began practicing tiger crane kung fu in conjunction with acupuncture treatments and qigong breathing exercises, I’ve lost nearly fifty pounds, eliminated the need for pain medication, and gotten completely off the steroid inhalers and proton pump inhibitors I’ve been using for most of this century. Results like that would make anyone a believer.

Up in the Northwoods, there’s a very small island that I like to visit in one of the lakes that I zip around. I have no idea if it has any sort of official name, but I’ve dubbed it Kung Fu Island. I’ve repeatedly tied up the boat to one of the trees on its rocky edges and climbed up to practice kung fu blocks, blows, kicks, and patterns on the soft bed of dry, reddish-brown pine needles that cover the dusty soil.

Practicing a lengthy pattern – a predetermined series of kung fu movements meticulously passed on from sifu to student – there under the towering evergreens, deep blue sky, mountainous clouds, and blazing sun is a fundamentally different experience than working on it in an indoor, urban setting. Ditto for doing deep-breathing qigong exercises while inhaling the clean breeze blowing off the lake and meditating between the trees while surrounded by the sound of the wind.

Memories of kung fu lessons, practice sessions, discussions, books, articles, comics, movies, television shows, and videos swirl around me, and I feel less like I’m in upper Wisconsin and more like I’m at the Shaolin Temple in its long-ago glory days. Named for Shaoshi – the mountain beneath which it lies – and the lin (“grove”) within which it sits, the monastery has an array of legends that have built up over the decades and centuries around its relationship to the martial arts.

Those legends color my experience of practicing on the island as much as the fairy tales color my experience of the forest and The Hobbit colors my experience of the rising smoke. Without the stories, physical exercise can be a tedious drudge. With them, performing the movements over and over feels like a gift as it connects me to all those who are performing the movements elsewhere in the world now and all those who have performed them over the immensity of past years.

Even when throwing a punch alone into the air, I am not alone, and the air is not empty.

The Thunder

Am I hallucinating? No. Am I astral projecting? Absolutely not.

As they swirl around inside of our minds, our stories coalesce into a poetic gloss on our lives. They form a lens through which we view the world. You might even say that they constitute our worldview.

The more stories we know, the more deeply we know them, the more intensely we feel them, the more they add depth and richness to the lives we live. When they are connected to powerful memories (like my earliest forest walks with my father) or repeated actions (like practicing a kung fu pattern), they even more powerfully affect how we understand our experience of the moment.

This is, fundamentally, how I relate to religion. The stories are what mean the most to me and have the strongest presence in my daily life.

When I am alone in the forest, and there is an indefinable hush that seems full of expectation and presence, that is when I feel that Odin is near, in his guise of the wise wanderer.

When the thunder is so extremely loud and so incredibly close that the entire house shakes to the point where part of me wonders if the walls will hold, that is when I feel that Thor is near, the wheels of his chariot grinding as they roll across the clouds.

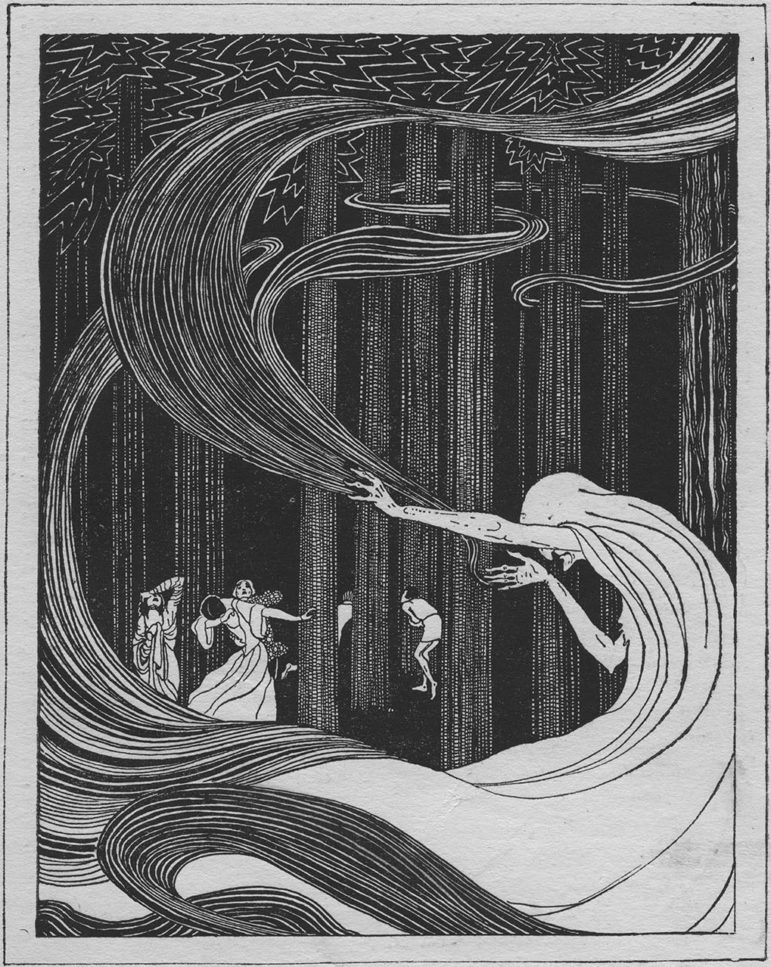

“A great thunderstorm scattered them in every direction” by Jennie Harbour (1921) [Public Domain]

I have these feelings because of the myths, because of the stories. The historical fiction of the Icelandic sagas is indeed wonderful, but it affects me less than the wonder of the legendary sagas that tell of dragons and dragon slayers, dwarfs and dwarf-forged swords – even though those legends are themselves built up around historical personages such as Sigebert and Brunhilda, Attila and Theodoric.

Tolkien was famously opposed to allegory but embraced applicability. The latter approach is indeed closer to how story works in our minds.

I’ve met many Lokis and Gollums, as I’ve met a few Odins and Thors. I’ve seen vistas while traveling in Iceland that seemed like I was looking upon the walls of Asgard or watching Frodo and loyal Samwise determinedly walk towards the setting sun. Over the last few years, I’ve often felt that the forces of darkness are gathering for Ragnarök, and the giants are determinedly tearing down the world around us.

When I teach about the myths and legends of England, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, India, and elsewhere, I hope that at least some of the students will embrace the stories. I hope that the tales can become part of their lives as they are part of mine, and that – when the storm is strongest – they will think of Thor, if only for a moment.

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.