ANAHEIM, Calif. – On June 1, 2022, water restrictions officially began for many people in Southern California in an effort to mitigate the effects of a megadrought. Overall, the last two decades in California have gone on the record as the hottest and driest in the previous 1,200 years. However, many people are skeptical that the newest water restrictions, among the most sweeping and strict, can be effective.

Image credit: Richard Heim NCEI/NOAA – Drought Monitor [1] – Public Domain

Where California Gets Its Water

More than 19 million people receive water from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Of that water, nearly 25% comes from the Colorado River, already embattled and overstressed. Around 45% comes from local sources, such as water retreatment plants, groundwater, and even desalination plants. The State Water Project supplies the final 30% of the water—that is, until this year.

Because State Water Project resources have dwindled, California is on track to pull at least a third of its total water needs from the Colorado River in 2022, at a time when farmers in other southwestern states are leaving fields fallow because there is not enough water.

The State Water Project in California disburses water to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, as well as to other districts and vast tracts of farmland. In total, the State Water Project supplies water to over 27 million Californians and draws water originating in the diminishing snowpacks of the Sierras through the Edmonston Pumping Plant. During the winter of 2021-2022, the snowpack in the Sierras was only 38% of normal.

The period of January to March of 2022 hit the record books, according to the National Weather Service, as the driest in 101 years of recordkeeping at three different recording stations in California. Although the winter began with some promising precipitation, the late winter and early spring dry-up propelled California into its third year of drought.

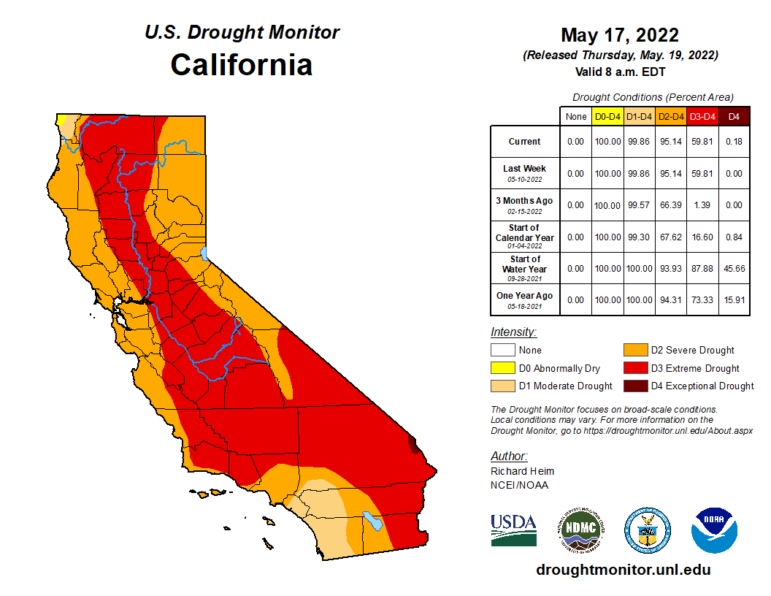

The area that the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) now classifies as D4—exceptional drought—is rapidly growing. More than half of California is currently in D3, which is extreme drought. No part of California is not in drought conditions at this time.

Where the Water Goes

Governor Newsom has encouraged people to reduce their water usage voluntarily, and many public officials have suggested that residents take shorter showers and use recycled water to water their lawns.

Garlic field irrigation – Image credit: NASA Goddard Photo and Video – CC BY 2.0

However, more than 80% of all the water used in California is for agricultural use, such as farming, and industries utilized around 6%. The remaining 14% of all the water used in California runs through the faucets, toilets, and hoses of nearly 40 million residents. But even that 14% is misleading—around half of residential water use goes toward landscaping.

And while residents in Southern California are more efficient than in Northern California or the Central Valley, usage does change depending on income. For example, residents in the wealthy Beverly Hills area use around 284 gallons a day, versus residents of Compton, who use around 106 gallons a day. The Metropolitan Water District supplies water to both cities.

Agricultural Giant

California agriculture generates around $50 billion, or nearly 3%, of the state’s GDP. Despite the pervasive droughts and dwindling water supplies, California grows more than two-thirds of the nation’s supply of nuts, fruit, and a third of all vegetables. It is the world’s fourth-largest wine producer and the leading dairy producer in the US. The US is the top global producer of almonds, grown in California.

Witching for Water

While many orchards, rice paddies, and lettuce fields stay vibrantly green year-round, not every farmer is able to tap deeply enough into the water supply. As locating water becomes more challenging, some have sought out water witches.

Some water witches like Rob Thompson are in high demand as ranchers and growers hope to find hidden water reservoirs. Thompson claims his dowsing success rate is over 90% accurate.

Thompson described water witching as a sort of magnetism, saying, “It’s like the energy between two magnets when they just pull you together.” Most water witches consider the practice a form of divination.

Wine growers are also turning to water witches to help locate water deep below California’s vineyards. Marc Mondavi, co-owner of Charles Krug Winery, has dowsed for the Napa Valley community for years.

After working with another water witch for several years to hone his abilities, Mondavi has found steady work helping growers to locate water. Drilling wells costs thousands of dollars, whether the drillers find water or not. Mondavi explains that the majority of growers in the area will consult a water witch first to increase the chances that they’ll drill in the right place.

The Challenge of Reaching People

Pinpointing exactly how much water California is currently consuming is a challenge. As of 2015, the US Geological Society (USGS) estimated that California was consuming 28,759 million gallons per day, or approximately 9% of the nation’s total water usage. The state with the subsequent highest water usage per day is Texas, at 21,268 million gallons per day.

However, staggering water usage numbers and photos of baked and cracked reservoir shorelines have not reached as many in the public as in years past. Many government and agency officials have stated their reservations about announcing and enforcing restriction mandates like in years past, citing worries that people are mandate-fatigued after several long years of COVID-19.

California State Senator Melissa Hurtado, a Democrat from Hanford, expressed her concerns about restrictions recently: “If we’re still not even over the (COVID-19) vaccine mandate and the testing mandate, and now you’re going to ask people to cut down on water consumption? That you should take less showers and you can’t get a new pool or whatever it may be? Yeah, no, that’s going to make people really angry.”

Many, including Senator Hurtado, are calling for fundamental changes in infrastructure and technology rather than asking residents to cut back. But the problems are here, now, with some communities already facing dry wells.

Mendocino’s wells ran dry in 2021, causing some restaurants to decide whether they could get enough water to stay open for the tourists the town depends on. People there hauled water from creeks to flush their toilets until the county and state-subsidized water deliveries.

A Vicious Water Cycle

California residents can report when wells go dry to a tracking system run by the Department of Water Resources. There has been a 63% increase in reported dry wells in the last year. In the last 30 days, the number of wells reported dry increased 26% over the previous 30 days as summer temperatures have arrived. Many communities rely on bottled water deliveries while waiting for truckloads of water that will then be pumped into storage tanks.

The worsening well problem for many communities is a result of a quickly-dropping water table. A law passed in 2021 did little to protect groundwater and gave agencies until 2040 to mitigate the effects of over-pumping the groundwater. And as the drought worsens, the pumping continues. In fact, as farmers and growers continue to pursue the groundwater aggressively, parts of the San Joaquin Valley have subsided or collapsed more than two feet.

The Outlook Is Dry

As California hits the midway mark of 2022 and the third year of the megadrought, many are also nervously watching for fires.

Owens Valley by Ross Stone

The traditional fire season is a thing of the past, with blazes popping up year-round that wreak widespread destruction and swallow entire towns.

Some officials are revisiting proposals once considered highly controversial to create water storage reservoirs. But there are no plans to radically alter the current infrastructure or reevaluate the agricultural model that produces so much of the country’s food.

In Northern California, water witches are getting more calls than they can possibly answer. In Southern California, people are mainly ignoring calls to limit watering to once a week, and some counties have not imposed any restrictions whatsoever. And Central California is gobbling up every single drop it can find.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.