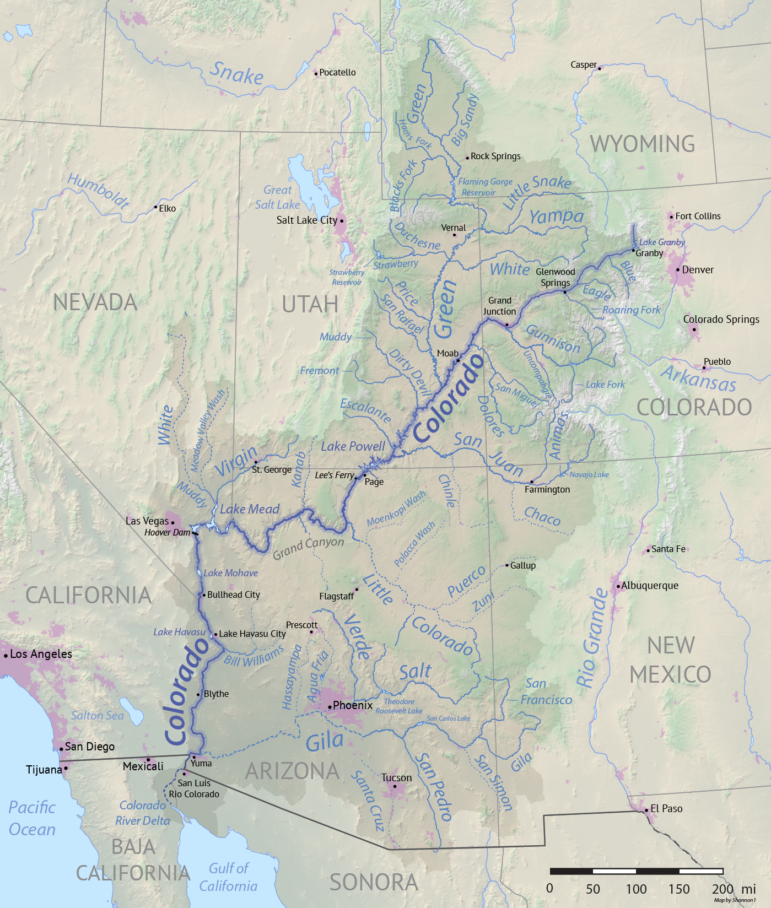

TWH – The 1,450 miles long Colorado River drains about 1/12 of the U.S. watershed in some of the most arid parts of the country, flowing through seven U.S. states and Mexico. 70-80% of Colorado River water is used to irrigate U.S. crops. While demand for its water is increasing, the volume of water in the river is decreasing.

Image credit: Shannon1 – CC BY-SA 4.0

The Colorado River Basin

In March of 2022, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy issued a fact sheet on Land, Water, and Agriculture in the Colorado River Basin. The basin covers almost the entire state of Arizona, about half of Utah, and about a third of Colorado. It also covers smaller parts of California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Wyoming, as well as small parts of Mexico.

Roughly 42.9 million people rely on the Colorado River for drinking water. Urban areas outside the Colorado River basin that depend on Colorado River water include Albuquerque, Cheyenne, Denver, Denver, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, and Santa Fe.

The Wild Hunt recently spoke via email with Colorado native and Pagan, Chas S. Clifton. He said, “The Colorado River begins in northern Colorado, on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park, and flows (when it flows) to the Gulf of California, leaving the United States at Yuma, Arizona, after dividing Arizona from California.”

Thirty-seven reservoirs store water from the Colorado River. Large reservoirs, like Lake Powell and Lake Mead, store Colorado River water. Both are artificial constructions and not natural creations. Lake Powell, in southern Utah, is at only 26% of its capacity. Lake Mead, between Arizona and Nevada, is at 34% of its capacity.

The Colorado River Basin and Native Americans

Thirty Native American tribes/nations live in the Colorado basin. Of those, 22 have rights to 22% of its water. However, Native American households are 19 times more likely to lack indoor plumbing than are White households in the U.S.

The Navajo or Diné have much worse water access issues. They are 67 times more likely than other people in the U.S to lack indoor plumbing. Between 30 and 40% of the Diné have to haul water to their households for daily use. While technically they have rights to its water, they lack the infrastructure to actually use it.

The Colorado River Basin and the global food supply

Water issues in the Colorado River Basin have a major impact outside of the basin. About 15% of U.S. crops and 13% of U.S. livestock rely on Colorado River water. Cotton is the third most common crop reliant on Colorado River water.

Imperial Valley in Southern California – Image credit: Spacenut525, Public Domain

Clifton said, “If this all seems remote, ask yourself, do you like lettuce? A lot of lettuce is grown around Yuma, watered by the Colorado River. Do you wear cotton clothing or sleep on cotton sheets? If that cotton comes from Arizona—and a lot of American cotton does—it is [was] probably irrigated with Colorado River water, stored at Lake Mead or other reservoirs. A lot of cotton farmers are currently unable to plant their crops, however, due to water restrictions.”

The multiple problems of the Colorado River basin will affect prices. The cost of produce and cotton clothing will increase. Clifton asked, “Are you going to change your food-buying habits when you are used to seeing the same fresh vegetable from January to December?“

The Colorado River Compact of 1922

Dr. Professor Elizabeth Koebele, Ph.D. of the University of Nevada, Reno wrote about the complex legal agreements to share Colorado River Basin water. Known informally as “The Colorado River Compact,” it estimated the basin to have an annual volume of 18 million acre-feet (MAF). An acre-foot equals the amount of water needed to cover one acre with one foot of water. The Compact allocates 16.5 MAF to six states and Mexico, with large reservoirs like Lake Mead and Lake Powell storing excess water.

Unfortunately, that 18 million acre-feet estimate was incorrect and scientists now estimate its annual flow to be 13 MAF with an annual deficit of 3.5 MAF. Climate change, drought, and population growth augment the water deficit. The states, tribes/nations, and Mexico have not renegotiated allocations to align with current estimates of the Colorado River’s volume of water.

Clifton said, “The states were slicing up a pie that looked bigger than it actually was. But everyone wants to get the size of slice that they were promised.”

In 2019, the U.S. Congress approved the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP). Under the plan, lower water levels in Lake Mead would trigger reductions in water allocations. In August 2021, low water levels triggered a Tier 1 Water Emergency. For Nevada, this means a 7% reduction in its water allocation. Southern Nevada gets 90% of its water from the Colorado River basin.

The DCP will expire in 2026. A renegotiation process has begun, and is likely to be contentious and politically fraught.

The Colorado River Basin and specific states: Utah

In addition to the Compact water deficit, the entire U.S. West is experiencing a severe drought. Higher temperatures linked to climate change increase evaporation, causing water in the river and stored in reservoirs to evaporate faster.

The Lincoln Institute published “Utah Makes Plans for a Water-Smart Future” reported that Utah’s Great Salt Lake has shrunk by half. While the Great Salt Lake lies outside of the Colorado River Basin, Utah’s Reservoirs are at 50% capacity.

Like much of the U.S. West, Utah is both arid and fast-growing in population. One effort involves coordinating land and water policies to create a sustainable future. The Utah legislature has developed a specific framework for community action.

Utah has developed a water reduction strategy to reduce per capita water use 16% by 2030 and 26% by 2065. While the state legislature has a history of conflict around water issues, Utah has backed a pilot project to reduce its water use.

“Growing Water Smart” is another initiative to mitigate water supply problems. The program works with community stakeholders and researchers. Together they would develop workable plans for their communities that are located in Arizona, California, Colorado, and Utah. The program’s goal is to coordinate land-use planners with water managers.

Hydropower

Dams in the Colorado River basin also produce about 5.5 billion kilowatt-hours through hydropower that are consumed by 5 million people in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico Utah, and Wyoming. The sale of that energy generates over $150 million in revenue. While most of the revenue is used for operation, a small portion of it funds programs such as the Upper Colorado Fish Endangered Recovery Program and the San Juan River Basin Recovery Implementation Program. They state that “both recovery programs focus on seven elements of recovery: instream flow, habitat restoration, nonnative fish control, information and education, propagation and genetics, research and monitoring, and program management. Each element contributes uniquely to stronger fish populations and healthier ecosystems to benefit people and fish.”

The funding of these programs is being impacted by the loss of hydropower from the ongoing drought. According to the Colorado Sun, hydropower could drop by as much as 38% causing these programs to seek funding elsewhere to maintain the projects. The programs are currently seeking alternate funding strategies. Teresa Waugh, the spokesperson for the Western Area Power Administration that markets the hydropower, told the Colorado Sun, “Persisting drought is the primary driver for the current and near-term Basin Fund balance concerns, which become particularly acute should reservoirs drop below minimum power pool elevations, and the probability of that occurring continues to increase.” But the good news is that none of the program partners have ceased their support of the programs.

Possible Signs of Hope

Professor Kerri Jean Ormerod with the University of Nevada, Reno wrote about ways to target water re-use investments to address the Western Drought. She bluntly stated that two alternatives exist. People can either reduce demand or increase supply. To increase supply, she argued for “Reuse of highly treated municipal wastewater, known as reclaimed water or recycled water.”

Montebello Forebay Ground Water Recharge Project in Los Angeles, California – Image credit: EPA – CC BY-SA 4.0

Wastewater has the distinct advantage that as the population increases, the amount of water to be recycled also increases. Increased water conservation would also play a key role.

Ormerod stated that the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill passed by Congress provides funding for new water projects. The Environmental Protection Agency will distribute $7.4 billion this year to states, tribes, and territories. That money would develop water infrastructure over the next five years, resulting in the government distributing $50 billion. Of those funds, $1 billion will fund water reuse grant programs for large-scale projects. Ormerod noted that these funds from the Infrastructure Bill could be transformational.

Clifton brought up another, more holistic solution. He said, “Any solution is going to involve both nature and politics. Here at the headwaters, we will be learning the relationships between forests and water flow. In late 2020 the East Troublesome Fire burned 192,500 acres (77.930 ha) up where the Colorado River begins. I hope that efforts to rehabilitate the land will include more beavers. Beaver dams change the water flow in high-country valleys, making the land spongier, raising the water table. Instead of water that rushes down in late May and June following snowmelt, streams below beaver dams rise more slowly but run for a longer time.”

“Pagan equals ‘local’ in some situations,” Clifton continued. “At my house, we grow what we can, and we often replace shipped-in spinach with quelites, wild greens that come back every year, like lambsquarters and wild amaranth. We still wear cotton, though, but we try to make it last. We are not hardcore locavores, but we think about these things.”

Clifton said, “On the macro level, renegotiating the Colorado River Compact will move about as fast as politics in the Vatican. … Agriculture will take a bigger hit than cities like Phoenix or Las Vegas —and when that happens, all Americans will feel a ‘disturbance in the Force.’”

The Wild Hunt has previously reported on water issues in the Colorado River Basin.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post, visit The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new comments in our subreddit.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.