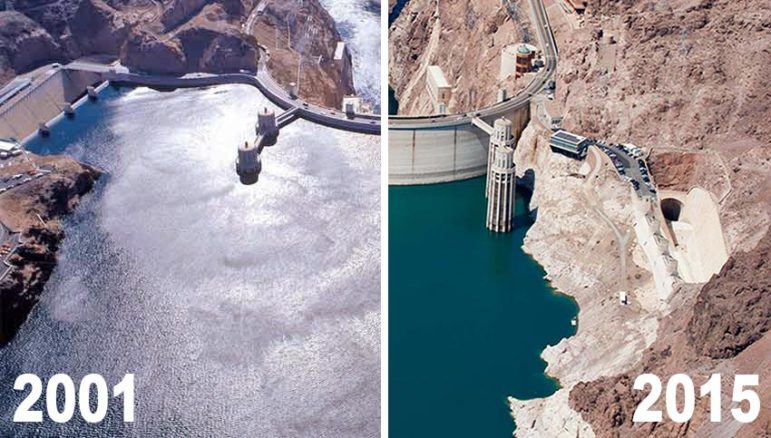

TWH – On August 16, the U.S. declared a water shortage at Lake Mead, which functions as a reservoir and stores water from the Colorado River. In 1983, the lake reached capacity. It hasn’t been that full in the 38 years since then.

This declaration means a loss of Arizona’s water allocations from the Colorado River. Starting in January 2022, Arizona will begin to lose 20% of its allocation of water. Nevada and Mexico will face smaller reductions in their water allocations.

Image credit: National Park Service – CC BY-SA 4.0

Hydrologists have already issued a dire forecast for that lake. They projected that the lake would only be at 34% of its capacity by December 2021. Lake Mead in addition to supplying water to Arizona, California, and Nevada, also sends water to parts of Mexico.

A more serious water shortage exists further south. In its natural state, the Colorado River emptied into the Gulf of California. National Geographic reports that “the Colorado River no longer reaches the Gulf, and instead peters out of existence miles short of the sea.” The Colorado River once carved out the Grand Canyon. Now, it dies before it reaches the sea.

In 2019, seven US states negotiated the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan. That plan is intended to manage declining water levels in the Colorado River. The August 16 declaration of a water shortage marks the first time that plan has been used. Those negotiations also involved Mexico and 29 sovereign Native American nations. The plan sets up a tiered system to reduce water allocations. Specific water levels in Lake Mead trigger specific reductions.

Those negotiations failed to reach conclusions about more serious declines in water levels. The Contingency Plan has no accommodation for when water levels fall below 312.4 meters (1,025 feet). The Bureau of Reclamation estimates that it will fall to 324.9 meters (1,066 feet) by January 1, 2022. It hasn’t been that low since the Hoover Dam created the lake in the 1930s.

On September 13, the electronic talking circle called Native America Calling hosted a discussion about these water shortages and Native American Tribes. Participants included Dr. Melissa Nelson, a Chippewa Indian and professor at Arizona State University, and Matthew Leivas Sr., a Salt Singer and elder of the Chemehuevi Tribe. They also discussed how those tribes are preparing for a future with less water.

Nelson described how Native and Western cultures differ in their understanding of water. She said, “For us, water is a relative, not a resource … Water is an ancestor. We are water.” She said, “For us, it is not a resource outside of us that needs to be managed … It’s actually a sacred element that we are enveloped in. We need to nurture, conserve, protect and restore it.”

More cuts are likely

The Bureau of Reclamation forecasts dropping water levels for the next two years. More allocation reductions loom ahead for Arizona and California.

Jennifer Pitt, of the Audubon Society, said “Climate change is water change. We can no longer rely on the fact that we know what the hydrology is going to be in the Colorado River basin, and that has water managers worried.”

The drought

The Colorado watershed has had roughly two decades of drought. Those twenty years have depleted reserves. Decades-long droughts have occurred in the Southwest before. Climate change intensifies droughts. Hotter temperatures dry out the soil. The drier the soil becomes, the more water it absorbs. That absorbed water never reaches the river.

A closer view of just how expansive the drought has been (notice the boat along the rocks for size comparison). About 100ft high – Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey from Reston, VA, USA – Public Domain

Hotter air increases evaporation from the river and its reservoirs. That evaporation further decreases the volume of water. In 2020, scientists estimated that a million acre-feet of water evaporated from Lakes Mead and Powell. Humans constructed these “Lakes” as reservoirs. They did not emerge from nature.

An acre-foot is a volume of liquid (in this case irrigation water) that would cover one acre of land with one foot of liquid. One acre is about 4,047 square meters and one foot equals about 0.3 meters.

What is the Colorado Compact?

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 governs water allocations from the Colorado River. That Compact had worked with an estimation that the Colorado River had an annual water flow of 17 million acre-feet of water. They based all their allocations on that estimate. Unfortunately, that estimate was based on the unusually wet series of years from the 1900s to 1922. It has proved to be overly optimistic.

The Colorado River supplies water to 40 million people in seven states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. It also provides water to northern Mexico and 29 sovereign Native American Nations.

The Colorado River forms the eastern border of the lands of the Chemehuevi, who live on the California side. Leivas Sr. spoke about their spiritual relationship with water. He said, “Water has life and memory. Our people will sing to the water.”

Leivas said that since 1983 the amount of water in the river has changed. In the 80s, the Bureau of Reclamation started opening up the dams. They wanted to release the sediment trapped by the dams to increase water flow. The sediments flowed downstream. The stretch of the river that borders his reservation had been clear. Now, their view of the Colorado River has mile-long sandbars in the middle. Those sandbars have damaged his tribe’s fisheries and created navigational hazards.

Water from the river also produces electricity for the area between Arizona and Wyoming.

On August 8, The New York Times reported that “about 70 percent of water delivered from the Colorado River goes to growing crops, not to people in cities.” In 2020, water extracted from the Colorado River irrigated farmland. That farmland produced 90% of the winter vegetables in the US. It also reported that 8% of the US GDP depends on water from the Colorado River. If reductions in water allocations continue, agribusiness will have to make hard decisions.

In December 2014, two representatives from the Bureau of Reclamation reported that the Colorado River has “an average “structural deficit” of 1.2 million acre-feet [of water] a year.” That deficit has much more to do with overly optimistic allocations than with drought related to climate change. Together, however, they create a bleak prognosis for the Colorado River and its dependents.

The role of reservoirs in hiding the problem

Water managers say that they had saved enough water for the system to work for a while. That time has run out. Even without a drought, the system is extracting more water than is being replaced. This is not sustainable.

Intake towers of Hoover Dam in Lake Mead on the Arizona side (2007) – Image credit: Waycool27 at English Wikipedia – Public Domain

The water stored in Lakes Mead and Powell, have, like credit cards, allowed people to spend resources that they lacked. Water levels are falling in both lakes and may soon reach a danger point.

Outlook for the future

Drought related to climate change combined with overly optimistic allocations portends continued water troubles. Officials believed they had plenty of time to deal with it before it reached critical mass. Those hopes appear to be wrong. Today’s water flow in the Colorado River represents a 20% decline from that of the 90s.

Nelson said that tribes were returning to traditional methods of irrigation, adapted for long-term drought conditions, such as the Zuni waffle garden. Tribes have also begun to switch to more minimal irrigation techniques such as drip rather than aerial irrigation.

In a hot, dry climate, aerial spray can evaporate before it hits the ground. Nelson stressed that returning to traditional agriculture does not exclude adopting modern advances.

The watershed restoration projects form an important part of building sustainability along the Colorado River. Indigenous people are taking the lead in these efforts. Nelson noted the Grand Canyon Trust as an example.

They have organized “intertribal conversations and environmental leaders on the Colorado Plateau” about protecting and restoring the river. The Elders emphasized prayer and ceremony, as well as working well with scientists.

They stressed building trust in dialogue with many stakeholders. A coalition of tribes along the Colorado River are “working to restore and protect some of these beautiful sacred places for everybody, not just for their own tribes, but for the animals, for the plans, [and] for future generations.”

Nelson said, “indigenous people need to be at the forefront leading these conversations because we have a millennia-long history going back 10,000 years, plus of stories about how we care for the rivers, the springs, [and] the freshwater sources. Traditional ecological knowledge needs to be respected again and included in all future water planning.”

Climate change may soon force people to make difficult decisions. Some coastlines may be abandoned. Some suburbs and small towns may be too wildfire-prone to sustain. Some populated areas may face water shortages.

The phrase “managed retreat” is starting to be used.

Abraham Lustgarten recently wrote the “the uncomfortable truth is that difficult and unpopular decisions are now unavoidable. Prohibiting some water uses as unacceptable — long eschewed as antithetical to personal freedoms and the rules of capitalism — is now what’s needed most.”

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.