Editor’s note: Today’s offering contains descriptions of eye trauma.

When she last came to visit, my best friend left a bottle of wine behind.

“It’s Odin’s,” she said. “He wanted it. I just didn’t find a good time to give it to him.”

I let it sit on my shelf for months, waiting to find a time to drink it, or offer it, or pour it out. It wasn’t that I didn’t work with the Old Man – although our relationship has been a bit touch and go. I’d started up working with him again during Yuletide. His altar was back in place, and I’d even bought him a few more trinkets for it – but it didn’t seem urgent to offer anything. I was busy. Polytheism offers a full social calendar for those of us who like making friends. I had other appointments.

* * *

Years ago – sometime at the start of my journey with Paganism – I had a dream. In it, I walked through a dark house – the house from The Babadook, which even in the movie is a metaphor for the conscious mind – and out into a bright backyard. Then, as one does in a certain type of dream, I took a rope and hung myself from a large tree. I dangled there, perfectly comfortable, as ravens pecked out my eyes and tongue. When I complained that it would be very difficult to make do without either, they replaced them, one crawling in to attach itself and become flat and pliable in my mouth, the other nestling into the socket of my right eye.

When I woke up, my eye ached. For months afterwards, I had a sense of it being hollow or unfocused, enough so that eventually I went to a doctor and asked them to look to see if anything was wrong. I was sent away with a clean bill of health and not even a change to my glasses prescription to explain the constant, distant pressure.

Eventually, as these things tend to, it became a part of life. Most of the time I didn’t even notice, unless I was meditating. Most of the time, I didn’t think about it at all.

When I did think about it, though, there was a twinge of fear. The folks I know who work with Odin, after a certain age, have remarkably similar medical histories. Eye trauma features heavily: cataracts, glaucoma, the sorts of illness that require long periods with eye patches or new, glass eyes to fill out empty sockets. The day my partner looked at me and held up their hand, covering one eye and nodding as if something made more sense, sits with me still on some nights.

“What are you looking at?” I’d asked, and they just shook their head.

“Just seeing how you’ll look,” they said, as if it was a normal thing to say, as if the sight of a beak jabbing in between my lids wasn’t lodged in my brain.

That was only one day. Most days my eye was fine, and I was busy with the mundanities of life, and I didn’t think of Odin at all.

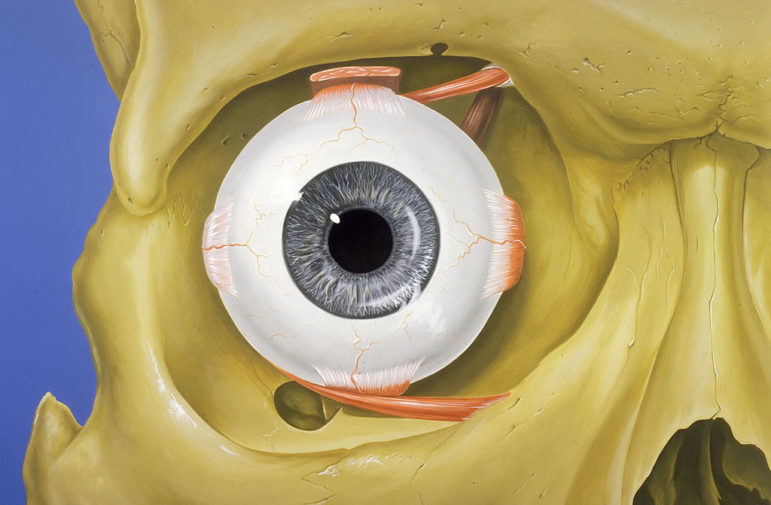

Normal anatomy of the human eye and orbit, anterior view [Patrick J. Lynch, Yale University Center for Advanced Instructional Media Medical Illustrations, CC 2.5]

Still, the threat of losing my eye was why I told him, at long last, to leave. After a particularly nasty jolt evening, a year passed with his altar in a box at the base of my closet, wrapped in black and tucked where there was no chance of touching it by accident. It was a year of learning how to set boundaries, and with him I set them firmly – no engagement, nothing, no word to me or my family until the allotted time had passed. The year after that, I brought him back out and wrote a contract, on Yule, with much more specific agreements and limitations. I didn’t trust him, I wanted that to be clear, but I was willing to hear what he had to say.

The problem, I knew, would be holding those boundaries. Like Tyrion Lannister, I too have a soft spot for bastards, and there is a certain sort of unrepentant con man that I’m hard-pressed to stay angry at. A hard stop was easy enough to enforce, but maintaining my position against someone who was in turns wheedling and threatening but always charming sounded like my own personal brand of sisyphean task. I wanted to feel safe – but even C.S. Lewis knew that gods aren’t safe. Barring that, I wasn’t sure what boundaries I had that I could expect myself to hold.

For a while it was fine – another calm year, with enough distractions and other tasks that I didn’t think much about him, at all. I bought him something small as a welcome back present, but mostly I thought about other things and went about my life. My friend came to town, and left her bottle of wine, and I glanced at it occasionally and wondered whether I’d find a reason to offer it. The connection between us didn’t feel safe or dangerous. It didn’t feel like much of anything, after a while.

“Just One Eye” [Dxerd, Wikimedia Commons, CC 4.0]

This might have gone on for ages, forever. When I next moved, he might have gotten packed into a box and never unpacked, left in a part of my life that I had no more connection with. I might not have noticed the difference – if one day, the ache in my eye hadn’t turned into a shooting pain.

This time, in my dream I felt it as an ice pick. I could find exactly where it entered into my skull, exactly where it crossed out the back of my head, exactly how it severed nerves and crushed delicate systems on the way. I covered it with my arm and stared at the landscape with my good eye, panicked and knowing exactly who had done this.

When he showed up I was nearly hissing in fear and pain. “What do you want?” I asked, feeling the hole beneath my palm where the globe of it should be.

“I want to be important to you again,” he said. He was emphatic – the word that came to me was deranged, which fit the god of madness. “Wasn’t I important to you? I’ve given you so many gifts.”

“I didn’t ask for your gifts,” I said, trying to think of what he might mean.

“But you benefited from them,” he pointed out, looking smug. “It doesn’t matter who you thought bought the cheeseburger – you ate it.”

“Aren’t you the one who said -” I paused, breathing around the panic of a missing eye, an impossible wound. “Didn’t you say not to be too generous in your giving, because you won’t get things back? I didn’t ask for them. I am not responsible for what you gave to me.”

He beamed and the fear vanished, the pain was gone. “Oh,” he said, reaching out to drag me into a hug. “You listened.”

I woke up gasping, reached up to my face and found no wound, no ache. I was shaking, drenched in sweat. “What gifts?” I asked the empty air, and laid down to try and sleep.

“You need to make a decision,” one of my partners said the next day, zir face filled with worry. “If you’d told him no or yes, this wouldn’t have gotten this far. But you’ve been indecisive, and it’s stringing both of you along.”

When I asked my other partner what they thought, they just laughed. “I mean, the whale’s going to eat you either way. I don’t blame you for running.”

I dug through my memory, dredging up Jonah’s particular situation. “I thought the whale only ate him because he ran?”

They tapped the ridge of my eye socket, looking amused. “Would this have happened, if you hadn’t run?” they asked.

A child wearing an eyepatch with artwork of the Star Wars character Yoda on it [Melissa Gutierrez, Wikimedia Commons, CC 2.0]

The question, for me, is always about boundaries. If a friend of mine made a credible threat to take my eye once, over drinks, that would be an end to things. On the other hand I will forgive spirits almost anything, struggle to see the metaphor or the reasoning, wonder if, perhaps, my boundaries are restricting my own growth. Surely someone so old and knowledgeable has reasons for their actions, I tell myself. Surely there’s a lesson in it.

I am not sure this is to my credit. Perhaps the lesson is that forgiving, and expanding my boundaries, is a bad idea. Perhaps the lesson is in the work of defending those boundaries, of making them clear and inviolate, of enacting my will over the domain of myself. Lessons are valuable. They can be learned in different ways, and from people who do not threaten or cajole. Lessons are things I can teach myself.

In my more skeptical moments, when I think I am just interacting with myself, I think about the emotions that the spirits I engage with show me. When I don’t call, they miss me. When I avoid them, they can be hurt. When they’re hurt, they can lash out – in ways and to degrees that outstrip the imaginations of most of my friends.

It makes sense, if it’s all a metaphor. If I avoid or disregard a part of myself for too long, it has a tendency to drag my attention back, biting and spitting at the pain of being untended. It’s my job to soothe those hurts and tend those wounds, to coax myself back towards something like equilibrium. In the moments that I believe I am speaking to someone outside of me, the thought of hurting them feels me with regret – but while I can show compassion and care, I cannot heal them in the way I can heal myself. How do I balance divine love with my own safety?

I know the Old Man too well to trust him. Still, the day after my dream I thought long and hard about my own poetry, about the raven that lives in the socket of my eye and whispers secrets of the world. I thought about my many gifts – and I opened the bottle of wine.

The Wild Hunt always welcomes guest submissions. Please send pitches to eric@wildhunt.org.

The views and opinions expressed by our diverse panel of columnists and guest writers represent the many diverging perspectives held within the global Pagan, Heathen and polytheist communities, but do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wild Hunt Inc. or its management.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.