Mindfulness is all around us. It’s been a trendy thing for many years, but it still surprises me how ponderously po-faced people can become the moment it’s invoked.

Balls by Bertha Boynton Lum (1922) [Library of Congress]

When I was working on a divinity school graduate degree, there was a weekly interfaith gathering that featured a different speaker each session. After attending several of these meetings, I realized that it wasn’t really interfaith in the broader sense, but mostly served as safe space for Christian ministry students to practice giving sermons.

One presenter was a very awkward grad student, clearly tasked with incorporating mindfulness into his sermonizing, who began by asking us all to close our eyes. As an admittedly grumpy Heathen, I instead quietly watched what went on. He asked everyone to think about how their toes felt.

“Are they relaxed? Are you clenching them? Really feel your toes.”

I managed to not giggle at the deep toe-based spirituality being practiced by this very serious congregation during a supposedly interfaith moment within a supposedly secular academic department.

The grad student then moved up through various body parts (“really feel your glutes”) before suddenly pivoting right into his pre-prepared sermon on some aspect or another of some Biblical text or another.

More recently, I participated in an equity workshop that began with a mindfulness exercise. The moderator ran through the various instructions (“really feel your forehead”) in a near-monotone, as if reciting required warnings about side effects at the end of a sexy and sunny pharmaceutical commercial.

Again, I discretely watched everyone take this survey of body parts incredibly seriously, right up to the moment when the moderator suddenly switched over to her first PowerPoint slide on the specifics of embracing advocacy within the context of racial equity.

In both cases, the concept of mindfulness was brushed aside as soon as the requisite moment was done. It very much felt like a box had been checked, and there was no real through-line to the subject on which the rest of the gathering centered.

There was also an uncomfortable feeling that we were being pushed into performing a spiritual practice that had been completely shorn of its spiritual context.

Siri, what is mindfulness?

The website mindful.org offers a definition:

Mindfulness is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us.

Mindfulness is a quality that every human being already possesses, it’s not something you have to conjure up, you just have to learn how to access it.

The new agey language of commercial self-help really does stay fairly consistent over the decades, and it always reminds me of Rainier Wolfcastle’s narration of the Nature’s Biggest Holes documentary on the 2003 “Special Edna” episode of The Simpsons (appropriately backed by the meditational music of Sting):

From the widest gully to the deepest trench, holes define who we are and where we are going. And although Rover here may not know it, he is participating in a ritual as old as time itself – he is giving birth to a hole.

The mindful website (lower case website names are apparently meant to exude sincerity) goes on to explain that mindfulness can be practiced while seated, standing, walking, or moving as “short pauses” are inserted into daily life. Amazingly, it seems mindfulness can be done for a few seconds right at your workstation without even having to clock out, which helps explain why employers love it.

The billion-dollar mindfulness training industry is bolstered by giant corporations encouraging their employees to embrace the practice, not for personal growth but because it has been shown to cut employer payouts for healthcare and to increase employee productivity. Unsurprisingly, religious elements have been stripped from this marketable manifestation of meditation.

UC Santa Barbara Emerita Professor of Religious Studies Catherine L. Albanese says, “With business meditation, we have a practice that is extrapolated from Buddhism and secularized so that all of the theological underpinnings are swept away. So we have Buddhism stood on its head. Mindfulness meditation has been brought into the service of a totally different perspective and world view.”

The mindful site emphasizes that mindfulness isn’t connected to the “exotic” in any way:

Mindfulness is not obscure or exotic. It’s familiar to us because it’s what we already do, how we already are. It takes many shapes and goes by many names.

In other words, members of the white, Christian, middle-class workforce needn’t worry that they’ll accidentally do something Buddhist while performing their brief mindfulness exercises at the office.

Mayo Clinic’s webpage on mindfulness exercises makes no mention of religion or spirituality, let alone Buddhism or Hinduism. Strangely, Mayo Clinic staff assert that the practice of mindfulness is simultaneously a focus on nonjudgmental internal feeling and an engagement “with the world around you.” The benefits promoted include help for a wide range of health conditions and (of course) improved work efficiency.

The University of Minnesota webpage on mindfulness (“Brought to you by the Earl E. Bakken Center for Spirituality & Healing”) promises fundamental transformation of “how we relate to events and experiences.” Down at the bottom of the page, there is an acknowledgment that “the practices that cultivate mindfulness originally come from a more than 2,500 year-old Buddhist tradition.” However, the blurb goes on to emphasize that today’s mindfulness practice has already been “adapted into a secular context that did not incorporate the original cultural or doctrinal elements.”

Aside from this strangely open admission of cultural appropriation, the Minnesota webpage critiques a way of living in which we “spend large parts of our lives on auto pilot, not aware of what we are experiencing, missing out on all the sights and sounds and smells and connections and joys we could appreciate.” Instead, the “expert contributors” assert, we should embrace a form of mindfulness that cultivates awareness and focuses attention on what is occurring.

Taking these three explanations together, it’s clear that Asian religio-spiritual meditation has been willfully genericized, secularized, and morphed into a commercialized practice of hyperawareness that simultaneously centers on what Mayo Clinic calls “body scan meditation” (focused on relaxation of toes, glutes, etc.); conscious survey of internal thoughts, feelings, and reactions; and careful parsing of what is happening at the moment in the world immediately around us.

There is another way.

Oakland A’s and Odin’s ways

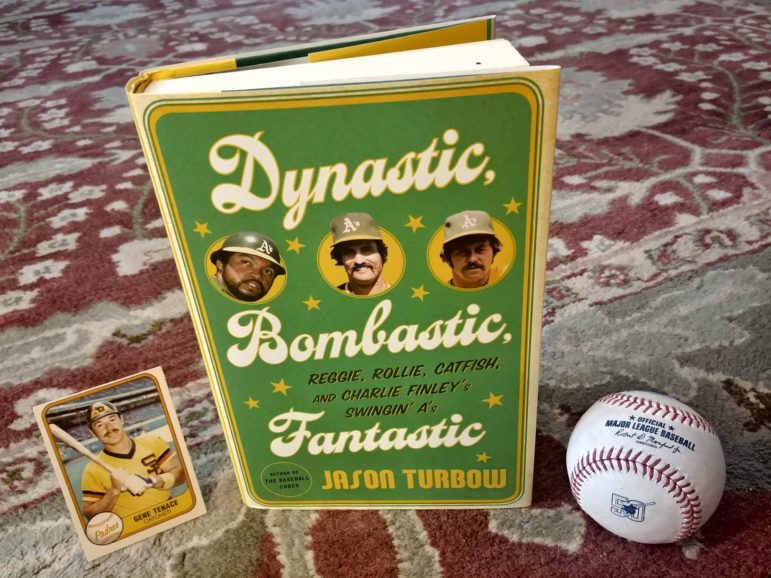

In his wonderful 2017 book Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish, and Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s, Jason Turbow describes the batting experiences of A’s catcher Gene Tenace in the 1972 World Series.

1981 Fleer card of Gene Tenace (as a San Diego Padre); hardcover copy of Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic by Jason Turbow; baseball from the August 9, 2019 Padres vs. Nationals game in San Diego [Photo by K. Seigfried]

During the second inning of the first game against the Cincinnati Reds, while waiting in the on-deck circle, Tenace thought he’d gone deaf. He absolutely could not hear what were obviously – to his eyes – 53,000 noisy fans in the stadium.

When he stood at the plate and faced pitcher Gary Nolan, the pitches looked so slow that they seemed to float to the plate. When the fourth one moseyed on by, Tenace slammed it over the fence. He didn’t feel the ball hit his bat, and he didn’t feel his feet hitting the bases as he rounded them.

His second at-bat went the same as his first, complete with deafness and time dilation, and he became the first player to hit home runs in his first two World Series at-bats. It wasn’t until the Michael Jordan era and its promotion of the concept of athletes being “in the zone” that Tenace finally realized what he had experienced in those long-ago glory days of the almighty A’s.

Reading Turbow’s colorful account immediately brought attributes of the Norse god Odin into my mind. We know him from Icelandic sources as the deity who inspires and possesses, who fills humans with mind and soul, and who unbinds the minds of his devotees as he makes them rage free of linear thought.

In 11th-century Germany, chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote of Odin’s Teutonic counterpart, “Wodan, id est furor” – “Wodan, that is fury.” In what Joni Mitchell calls “coincidences that thrill my imagination,” the full name of the great A’s catcher is Fury Gene Tenace.

What is so notable here is that the baseball moment of Zen was not about becoming more mindful in the sense of the mindfulness movement. It was not about becoming more aware of one’s inner world and surrounding environment. It was an opposite experience to that promoted by mindfulness advocates as it featured a shutdown of at least two senses and a lack of awareness of physical actions.

I’ve had similar experiences in a few different situations.

When recording electric guitar solos, I’ve sometimes gotten into a headspace in which the engineer hits record, I improvise a solo, he hits record, I improvise a solo – on and on, until something stops us and we go back to choose the best take. When this happens, I sometimes don’t remember playing the part at all.

When improvising on string bass, I usually play with my eyes closed. When things are really happening with the other musicians, I feel like I’m floating in a red space behind my eyelids, only dimly aware that the music is happening without intellectual decision-making and without conscious control of my hands.

When performing a kung fu pattern – a solo sequence of blows, blocks, steps, and kicks – or doing partner work to practice hitting and blocking, it’s impossible to think “now this punch, now that kick, now a turn.” The moves must flow, often in very quick succession. After weeks and months of work, the patterns and reactions simply happen on their own. “I do not hit,” taught Bruce Lee. “It hits all by itself.”

In these cases, who is choosing what notes to play? Who is listening to the backing track or other performers and reacting with a new musical line? Who is deciding what martial art moves to make in what sequence?

Some will answer that it is simply muscle memory in the body and chemical connections set down by much repetition in the brain.

Northern pagans of long ago had another answer: Odin. Whether through his gift of the creativity-spurring mead of poetry or through some form of possession, the wandering god opened human minds and filled them with burning passion. It’s an answer to the question of creativity that I find meaningful. It gives a face to that strange feeling that so many creatives have that our best ideas arrive from somewhere outside of ourselves.

In sports, music, and martial arts, the unbinding of the mind as it focuses upon a specific task is paired with a shutting down of other mental faculties. Senses are simply turned off in a subjectively very real way. Linear thinking evaporates as the Odinnic moment expands.

Rather than mindfulness, this is a process of unmindfulness.

Drifting into the light

When dealing with physical pains related to the repetitive motions of music performance back in the late 1990s, I was referred to a white-bearded hypnotherapist who taught me basic techniques of self-hypnosis.

Some specific moments of success with the practice stand out in my memory. During a long airplane flight above the clouds, I fell away from my body and floated thoughtlessly outside the aircraft. The pinging of the intercom and some announcement by the pilot brought me back to mundane reality with a bump.

I used to have a flashing light for the back of my bike that I would use for self-hypnosis. The pulsing light helped me get to a place in which thought and sensation drifted away and time lost all sense of measurement. I would completely forget what it was that was shining into my eyes, and I would come out of wherever I had been with a realization that I was actually looking at a physical light that had – for a moment – become something else entirely.

Our kung fu sifu teaches us to meditate at the end of every practice session. When I am able to really get into it after a lesson, after working out the moves at home, or going through the patterns by the waves at the lakefront, sounds take on a strangely distant and echoey effect as my thoughts move into the illogic of dream while sitting fully awake.

What the successful moments of self-hypnosis and meditation have in common is a disembodied feeling of drifting into the light. Whether focused on the pulsating red bicycle light or the bright sunlight filtering through my closed eyelids, the subjective sensation is one of the light growing larger and larger until it completely encompasses me and gently eradicates my flow of thought and cataloging of sensory input. In the times when the magic worked, I achieved unmindfulness.

For what have been called knowledge workers – for those who think through problems, develop responses to difficult questions, create creative works, and continue to learn so they can continue to teach – the floating away of the mind in unmindfulness can be a very attractive thing. As a writer, teacher, composer, and performer, the practices promoted by the mindfulness movement – of sitting at my desk and taking a brief time to focus on my thoughts and sensations – is far less appealing than the idea of taking a break from the continual firing of thoughts upon thoughts in a seemingly endless internal conversation.

I’ve met adults and children for whom the practice of mindfulness really is fulfilling. A very small person told me today that mindfulness work helps her to feel calm. I think that’s fantastic. A big part of finding yourself in this life is finding out what works best for you. Whatever my own feelings about the way in which mindfulness has been packaged and sold, I’m truly glad that it has helped so many people in positive ways.

For myself, and I suspect for many others, unmindfulness is a practice that simply offers something closer to what we really need.

At one end of unmindfulness, there is the shutting down of rational thought and sensory streams as Odinnic possession pervades our experiential frame and we focus on performance or creation. At the other end, there is the breaking free from the frenetic bustle of our brains and the diffusion of self into the light outside of time. Across the spectrum, we let go of control, desire, sense, and linearity as we float away from problems and pain, distress and difficulty.

Maybe we should start an unmindfulness movement. Even better, maybe we should simply encourage friends who would benefit to dig into Buddhist, Daoist, Hindu, and other forms of traditional meditative practice while being respectful of those who developed these techniques and without turning them into another product that can be sold to the corporate world.

May we all be lucky enough to experience even some small reflection of the ecstatic deafness of Fury Gene Tenace.

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.