Early on in David Lowery’s The Green Knight, there is a long shot where Gawain (Dev Patel) rides away from Camelot on his quest. Gawain’s loose yellow cloak is the only spot of color in the desaturated landscape; all else is a shade of gray or green. As Camelot recedes from view, another tower passes behind him while he rides, a squat and ruined place, somewhere already forgotten even at the dawn of the Middle Ages.

The Green Knight is a film of haunting and spectacular imagery, a delight for anyone who loves films for their ability to put otherworldly visions on the screen. But it’s this quiet, unremarked-upon image of the ruined tower that has stuck with me more than the phantasmagorical sequences elsewhere of witches’ spells and unearthly creatures. It demonstrates one of the most uncanny aspects of this film: how, with quiet confidence, it divorces itself from the long tradition of Arthurian filmmaking in the line of Boorman’s Excalibur (1981), breaking with the story-cycle approach to Arthur’s life. Instead, the Arthurian world, while still utterly fantastic, is already a place in ruins – a place already where the red world of humanity has been overcome by the green world of nature.

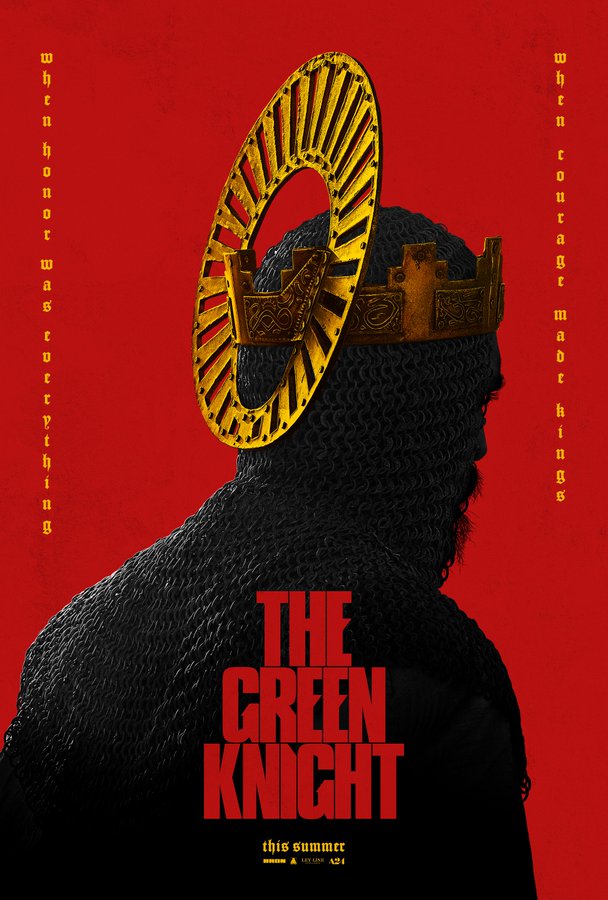

Theatrical poster for The Green Knight (2021) [A24]

The film takes its shape from the famous Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in which a strange knight, green in flesh and fold, arrives at Camelot on New Year’s Day and lays down a challenge: any knight there may deal him a blow, if he agrees that, in a year and a day, the Green Knight might give him the same blow in return. The still-young Arthur leaps to the challenge, only to have his nephew Gawain accept it in his stead. Gawain and the Green Knight exchange pleasantries, go over the terms of the deal – and then Gawain cuts off his head. Undeterred, the Knight picks up his head and says he will see Gawain in a year and a day.

Although the poem is unabashedly Christian – Gawain is a devotee of the Virgin Mary, keeping her image painted on the inside of his shield – the story has always been of interest to modern Pagans. The Yuletide beheading game of the Green Knight and the Red Knight (Gawain’s favored color) is often cited as an instance of the battle between the Oak King and the Holly King in Wiccan theology. And while the Green Knight’s color had a wide array of possible symbolic meanings to a medieval audience, to the modern Pagan eye, he reads as a being from the untamed, pre-Christian world of nature, standing in mischievous opposition to the civilized, Christian world of Arthur’s court.

The film makes a number of changes to this premise in its opening scenes. For one, the King and Queen (Sean Harris and Kate Dicke, never explicitly named Arthur and Guinevere) are aged figures, looking toward the natural end of their lives and thinking about what will come after them. They look to Gawain, Arthur’s nephew, who is not yet a knight, and ask him to tell a story of his own. “I have none,” he replies.

The previous scene has shown that heretofore Gawain has lived a hedonistic life, staying out with his lover Essel (Alicia Vikander) in a local brothel, a fact that displeases his mother, played by Sarita Choudhury. She conjures the Green Knight through spells written with Ogham staves and sends him to confront the King and her son. (Although much of the initial focus of the film was on the decision to cast Patel as Gawain, Choudhury’s performance as his mother, a combination of the legend’s sisters Morgause and Morgan le Fay, lends the film a mesmerizing postcolonial texture.) Gawain beheads the Green Knight at the feast, and, more hesitantly than his literary counterpart and still unknighted, sets off on his quest to find the Green Chapel.

The Green Knight (Ralph Ineson) himself [A24]

It’s here that the film diverges most from its source material. The poem alludes to Gawain’s many adventures while seeking the Green Chapel – “now with serpents he wars, now with savage wolves, now with wild men of the woods” – but these incidents pass by without any further explanation. Lowery stages this section of the film in several vignettes, indicated by title cards. “Sir Gawain and… The Journey Out,” “…a Kindness,” “…a meeting with St. Winifred.” Rarely does Gawain come out of any of these episodes unscathed: by the time he arrives at his final challenge, he has been robbed, bloodied, insulted, and even haunted.

There are a few ways to read these scenes, as Gawain descends ever deeper into his quest to find the Green Knight. One is as a hero’s journey, a bildungsroman, in which over the course of these trials Gawain’s character is tested – and usually found wanting. Another is that Gawain is, far from a noble hero, playing a pawn or fool. He is reminded constantly by those he encounters that the Green Knight’s challenge was only a game and that at any point he could turn back. Would Arthur’s court think less of him? Perhaps, though the film’s final moments seem to show he might still achieve his knighthood, great power, and courtly respect either way – at least at first. Like Sgt. Howie in Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973), Gawain is given opportunity after opportunity to turn away from his doom, but knowingly or unknowingly, he refuses each one.

In both the poem and the film, the heart of the drama is not in the Green Chapel nor in the Green Knight himself, but in a curious lover’s game played between Gawain, a lord (Joel Edgerton), and his lady (Vikander again). The lord gives Gawain shelter before his encounter with the Knight in exchange for a bet: the lord will go hunting, and whatever he catches will be Gawain’s; meanwhile, Gawain will stay home with the lady, and whatever Gawain obtains he shall give to the lord.

The lady (Alicia Vikander) offers Gawain (Dev Patel) a gift of a book in The Green Knight (2021) [A24]

The lady comes to him in bed and offers Gawain her green silk girdle, which she claims will protect him from all harm – a girdle exactly the same as one his mother gave him at the outset of his quest, which was lost along the way. Fearing for his life, he gives in to her temptations. The lady, though she holds good to her terms, gives him a cold dismissal along with the girdle: “You are no knight.”

As charged as the bedroom scene is (and Gawain’s subsequent “return of the gift” to the lord thereafter), the lady’s best scene is at dinner the night before, where she discusses the nature of the Green Knight and his chapel with her husband and Gawain. “While we’re off looking for the red, here comes the green,” she says. “Red is the color of passion; green, the color of what passion leaves behind.” She is telling Gawain, and us, about his breathless search for honor, a thing that Gawain cannot even explain when asked. But the boy does not have ears to hear her, not until it is too late.

The Green Knight is a slowly-paced film and never goes out of its way to explain why things are happening, though there are hints throughout of how Gawain ends up where he does. This deliberate speed gives ample time for the camera to fill our eyes with lush visuals and for the sparse script to fill our minds with its mysteries. An hour after I left the theater, I could only think about the ending, which is sharp, bitter, and hits like the final chord in a long symphony. But two days later, as I write this, I find myself thinking mostly about that lonely tower in the shot of Gawain riding from home, the green that overtakes the red.

The Green Knight is a rare picture, so easy to get lost within that while I soaked in its mysteries, I sometimes thought I might have lost my head.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.