Twelve years ago to the day, I boarded a flight from the Oslo-Gardenmoen airport in south Norway. I was heading for Tromsø, some 1100 kilometers (roughly 700 miles) north, where I was to start a new year of study and a new chapter in my life.

This plane ride was but the last leg of a much longer trip which started all the way in the southern French town of Beziers, where I lived, before leading to Paris, my birth place, and then Oslo, all through a combination of high speed trains, overnight bus rides, and ferries.

When I arrived in Tromsø, it was a typical Arctic autumn day, where massive gray clouds had only cold winds to compete with for the domination of the skies. As I left the airport, I grabbed unto my two massive suitcases, and headed for the other side of the island, where the campus was located.

When I got over the small patch of stubby birch woodlands that separate the western and the eastern side of the island, it was not the sight of the university that caught my eyes, it was the colossal heap of stones rising over the hills on the other side of the water.

It was a mountain. They call it Tromsdalstinden: the peak of Tromsø valley.

View of Tromsdalstinden in the fall. [Lyonel Perabo]

Sitting some 1238 meters (4000 feet) over sea level, Tromsdalstinden was the largest mountain I had ever seen. Growing up in the arid hills of southern France, I was more accustomed to landscapes made of vineyards, small dusty canyons and coastal inlets. I was completely unprepared for the view of this absolute unit of a mountain.

Towering over the surrounding hills, it shot in the heavens like the tooth of some primeval chthonic beast, capturing the attention of anyone letting their gaze meander eastwards. It truly and literally was a sight to behold, and it took me a couple minutes before I was able to turn my eyes away from the peak and go back on the task at hand.

In the following days and weeks, I kept encountering Tromsdalstinden again and again: while strolling in the city center, taking the bus to the university, hanging out at the harbor. I spotted postcards sporting its noble figure in the town’s souvenir shops and covers to books about Tromsø where it towered over the small town at its feet; I even saw it, just days into September, disappear into fog before reappearing, all snow covered, once a misty mountain, now a white peak.

In a town as small as Tromsø, with just about 60,000 souls calling the lonely arctic harbor their home back then, Tromsdalstinden seemed more like a benevolent and venerable neighbor than a mere pile of rocks. It was a landmark, a symbol, something to look to, and forward to.

As I wrote in a previous piece, in Norway, hiking and mountain climbing are elevated to the level of quasi-spiritual practice, with significantly more people spending their Sundays in the mountains than in the halls of churches. In Tromsø, a town quite literally enclosed by high mountains to the north, east, south, and west, hiking opportunities abound, but none is as coveted as Tromsdalstinden.

Despite being registered a class-four peak (the hardest), Tromsdalstinden remains surprisingly accessible. Starting in the city center, one can easily reach the top in four to five hours, with closer starting points making the whole hike even shorter. Still, it took me almost two years before I ascended it, having first tested my abilities on the neighboring mountains called Tønsnesvarden, Rundfjellet, and Fløya.

When I finally got the chance to make an attempt for the peak, I had the advantage of having with me my girlfriend (now wife) as well as a few friends. After taking the bus and getting off at the edge of the forest, we stepped into the wooded valley that stretches for miles, surrounded by peaks on three sides.

As the incline started to grow, we soon reached the tree line, and entered in what I recall thinking was the most Lord of the Rings-looking landscape I had ever seen. With every step up, rocks grew bigger, and lichen smaller, until the point only porous, sand-like soil stood in between the massive boulders on the edge of the peak, until ultimately, only rock remained.

As we stepped into the mountain’s grey ridge, the landscape to the north came into view, revealing nothing but dozens of kilometers of desolate rocky horizon. Between this barren scenery and us, nothing but the edge of the mountain, and a 300 meter (1000 foot) fall into the small glacial lakes below.

Closing in on the peak, I sighted in the distance the massive cairn marking the peak’s highest point, still surrounded on its eastern side by old snow from the previous winter. The path suddenly stopped ascending, and, before we know it, we had made it to the top. Behind us, the island, and beyond it, the archipelago, and then, more than 40 kilometers to the West, the open sea, azure and devoid of life and land all the way until the eastern shores of Greenland.

A view from the top of the mountain. [Lyonel Perabo]

After taking the time to take in such a view, we all took turns on the cairn, opening the rusty metal mailbox attached to the stones with metal wires. As if checking out of an art exhibit, we all left our names, place of origin and signature under today’s date, before heading down via the smoother southern edge. A few hours later and a few calluses later, we had come down safely to town, still moved by our walk.

In the following years, I got the chance to climb this peak a couple more times, every time thoroughly enjoying myself. Still, my personal experience with Tromsdalstinden remains limited compared to some locals, who may have reached its peak dozens, if not hundreds of times over the years. There is just something about that mountain that seems to attract people to it, as if it held some sort of secret spiritual power. It is a feeling I have had countless times since moving to Norway, driving down on the countryside, or sailing past an island, and seeing a mountain, so noble, beautiful, so unique, that I had to refrain myself from leaving whatever I was doing and climb that peak here and there.

As it stands, I might not have been the only one to have such an experience with Tromsdalstinden and other mighty mountains. The Sámi, the Indigenous people of northern Fenno-Scandinavia, who remained a steadfastly Pagan nation all the way until the 18th century, did retain ancient beliefs and traditions surrounding holy mountains and rocks, especially those of large size and peculiar shape.

Called Sieidi, those geological formations have been the recipient of offerings, prayers, respect and sometimes even fear by the Sámi population for hundreds if not thousands of years. While the neighboring Norwegians would routinely call these names such as trolls, shaman stones or Sámi-churches, they would nevertheless most often than not leave them alone, and dozens are still standing to this very day, some even adorned with fairly recent offerings.

The holiness of Tromsdalstinden, or Sálašoaivi in northern Sámi language, was, however, not all that well-known until, twenty years ago, the city of Tromsø, which was presenting its candidacy as a potential host city for the winter Olympics of 2014, planned to built a huge ski jump on the face of the mountain.

Almost immediately, opposition for such a project was voiced, not least by local Sámi representatives, who argued that defacing the mountain would be tantamount to spiritual desecration. In the face of this controversy, the Sámi parliament of Norway commissioned the artist and historian Hans R. Mathisen to write a report documenting the history of Sálašoaivi.

In 2004, when it was made public, the report indeed confirmed that the mountain had for generations been seen as a spiritual entity that one ought to show respect towards. When reindeer herders came by the mountain, for example, they would feed the reindeer thrice before departing, removing their hats and thanking the mountain for protection. Other researchers also pointed out a number of places in the immediate vicinity of the peak where possible offerings could have been made.

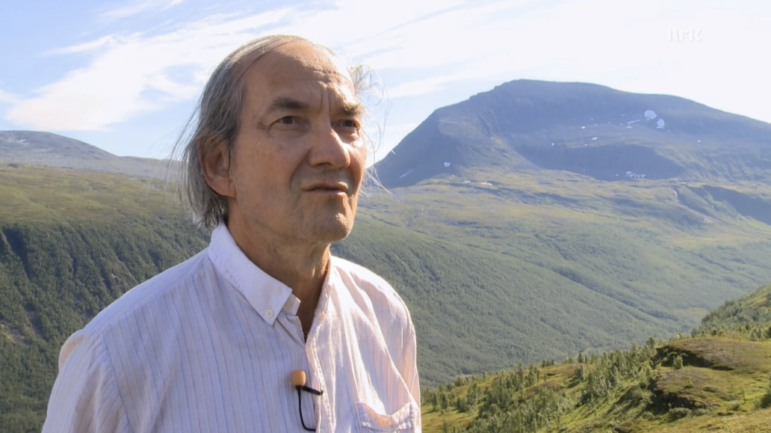

Ragnar M. Mathisen interviewed on the Norwegian national television network program Folk in 2010 [NRK]

At the end of the day, Tromsø did not get selected to host the 2014 winter Olympics (which went to Sochi instead) and the mountain was spared. Instead, it kept its role as the shining symbol of our town, ever-enticing peak from where one can see over the hills, through the fjords, and across the sea.

I might not have been able to climb it for a few years already, but I will never forget the many pilgrimages I once made on its rugged edge. I also will never be grateful enough for all the thousands and thousands of time when, in the middle of a dull or exhausting day, I gazed at its magnificence, and felt its holiness deep inside me, keeping my very own mountainborne faith alive.

THE WILD HUNT ALWAYS WELCOMES GUEST SUBMISSIONS. PLEASE SEND PITCHES TO ERIC@WILDHUNT.ORG.

THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR DIVERSE PANEL OF COLUMNISTS AND GUEST WRITERS REPRESENT THE MANY DIVERGING PERSPECTIVES HELD WITHIN THE GLOBAL PAGAN, HEATHEN AND POLYTHEIST COMMUNITIES, BUT DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE WILD HUNT INC. OR ITS MANAGEMENT.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.