“This feeling of wonder shows that you are a philosopher, since wonder is only the beginning of philosophy.” So said Socrates, according to Plato’s Theaetetus, a dialogue dated to around 369 BCE. He continues: “He who said that Iris was the child of Thaumas” – that is, of θαῦμα, a name that means “wonder” itself – “made a good genealogy.”

Theaetetus may have been left with a headache, and to tell the truth, so are many modern readers. But the central point of the dialogue was the idea of “wonder” as a driving force in the world that undergirds all knowledge in philosophy and science. It underpins our rationality through its connection with curiosity and awe. From our earliest moments, wonder is a feeling central to the experience of being human.

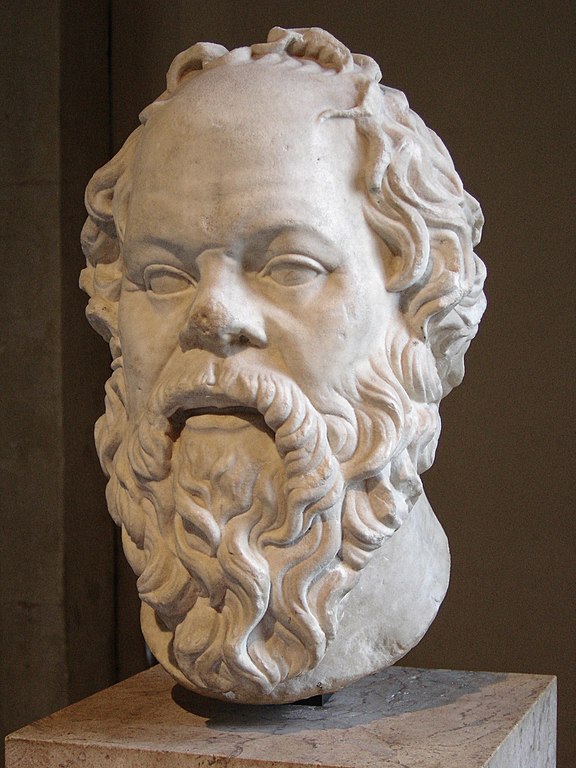

Portrait of Socrates. Marble, Roman artwork (1st century), perhaps a copy of a lost bronze statue made by Lysippos [public domain]

In the dialogue, Socrates is also saying that he sees potential in Theaetetus. Socrates sees Theaetetus’ sense of wonder and his readiness to do the heavy work in pursuit of truth. Socrates recognizes that wonder is dulled – even destroyed – by our unexamined assumptions of the world and of life. He sees Theaetetus’ willingness to rise to that challenge.

2,400 years later, psychological science is starting to look carefully at the idea of wonder. Clearly wonder is useful for asking the big philosophical questions. But does it have other benefits as well?

Wonder is clearly a positive emotion, and one different, perhaps subtly, from awe. Wonder leads from surprise to amazement, whereas awe seems to suggest some reverence and even fear. Fifteen years ago, research by Michelle Shota and Amanda Mossman identified distinctions with awe, and even earlier theoretical development suggested that wonder was more associated with curiosity, perhaps adding an impulse to examine and contemplate.

A few years ago, researchers at Texas A&M examined the language processing differences between awe and wonder. “When describing awe,” the team found, “people focused mainly on perception and observing novelty in their environment. Accordingly, they used more language related to perception than wonder. This conception of awe as a perceptual emotion may enable people to change their existing views of the world, and better adapt to new experiences. In contrast, when describing wonder, people focused on understanding the novelty in their environment.”

A major takeaway from the scientific scholarship was also the accessibility of the emotion of wonder. Early work by Kirk Schneider looked at integrating awe-based experiences as a means of promoting therapeutic gain especially for quelling the consequences of trauma and fear through mindfulness and gratitude.

Awe, however, still has roots in fear. Wonder can produce these benefits in a perhaps more accessible process.

A child looking up at fish in an aquarium [Pixabay]

“I have started to think about the value of ‘wonderment’, as against ‘awe’,” commented Simon du Plock, head of faculty of applied research and clincal practice at London’s Metanoia Institute. “I have even begun to question the notion of ‘therapy’ and to think about whether something more akin to ‘self-care’ might have a place.

“I think ‘wonderment’ [as] the secular equivalent of ‘awe’ might be a more helpful, less fearful, dare I say, less imperialistic, term,” he added. “I do not want to be in awe, and I do not want my clients to be in awe – I want us instead to recapture our innate ability to wonder. The ability to wonder comes from within us. It is not something frightening, a Higher Power which descends upon us from above.”

Trips to nature, the contemplation of art, the reading of a book or poem, experiencing new music, or a walk through a new neighborhood produce opportunities for wonderment. Wonder is ineffably accessible and its effects lasting and powerful.

Recently, researchers in Israel put that question to the test. The researchers constructed a study “aimed to explore the lived experience of the spontaneous creation in art by Holocaust survivor artists, and to gain new insight into the way creative engagement may relate to survivors’ traumatic past.”

The researchers conducted semi-structured interviews of 30 individuals who were both visual artists and Holocaust survivors, who discussed personally meaningful artwork. Their interviews were then analyzed using a thematic analysis technique that identifies codes and connections in the statements.

The Holocaust survivors consistently described the transformative power of marvel and wonder to overcome the personal horrors witnessed surviving concentrations camps and seeing their family members murdered. One theme that emerged from their responses was the rejoicing of life during the personal creation of art and the deep gratitude they had for the opportunity to express that beauty. The other theme described how the creation of their art induced moments of wonder that allowed a connection with a spiritual force.

The researchers noted that these findings did not describe fleeting moments of positive feeling, but rather lasting, healing transcendence. That sense of wonder created an opening through which the holocaust survivors in the study could re-engage with society after the deepest betrayal of community and safety. The participants used the creation of art to induce the benefits of wonder to overcome the despair and pain they witnessed and “behold the word afresh.”

The study highlights what du Plock would see as “everyday therapy,” that is, easily accessible, positively transcendent, and wonderfully effective.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.