TWH – In March 2021, Mexican archaeological officials filed reports with Mexican authorities that construction had begun on land near Teotihuacán, a site that forms the largest archaeological site in the Western Hemisphere. The reports stated that the construction threatened both existing and unexamined structures.

Avenue of the Dead at Teotihuacan – Image credit: AnbyG – CC BY-SA 4.0

When Mexican officials were sent to investigate, they found a fenced-in area with visible damage. The construction crew ignored orders to stop their activity. An online petition to stop the construction had 13,000 signatures as of late May.

According to the Associated Press, on May 31, the Mexican Government sent in 250 Mexican national guard troops and 60 Mexican police to stop construction.

Teotihuacán contains temples and represents a major indigenous center of Central Mexico. Jaime Gironés, international columnist for The Wild Hunt and author at Llewellyn Worldwide described how modern Pagans related to Teotihuacán.

Gironés said, “I know of some Pagan groups that visit Teotihuacán from time to time. I think that most of the people, regardless of their beliefs, see Teotihuacán with great respect and as a sacred site. Thousands of people visit the site, especially during the Spring Equinox, and you can find many types of visitors: tourists, indigenous groups, healers, New age groups, esoteric groups.”

Girones said these visitors seek an energy charge, a cleansing, “to perform a more elaborate ritual, or just to be there and see and feel the place. I see Teotihuacán as one of the most sacred places of our country, and as one that has become a modern spiritual meeting point. But we know so little about Teotihuacán and there is so much still to uncover that its safeguarding is crucial.”

In contrast, the construction seeks to build a recreation center. More precisely, they want to build a Ferris wheel.

The significance of Teotihuacán

Teotihuacán was one of the largest cities in the world from 100 B.C.E. to 750 C.E. At its height, 125,000 to 200,000 people lived there. It covered an area of around 20 sq km (about 7.7 sq. miles). Teotihuacán became the economic and political center of Central Mexico.

In 1987, The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated it as a World Heritage site and described Teotihuacán as representing the highest expression of Mexican identity.

According to UNESCO, the valley began to see an increase in inhabitants beginning around 100 B.C.E., though large-scale urban growth and actual construction of the city complex did not begin until around 1 C.E.

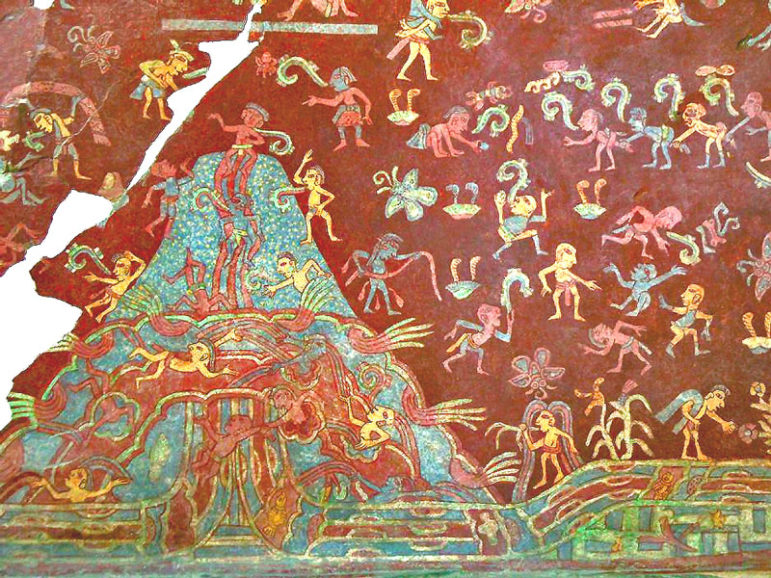

Teotihuacán has three world-famous monuments: the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Temple of Quetzalcóatl. The site also has magnificent murals.

Part of Mural 3, known as the “Paradise of Tlaloc” – Image credit: Robin Heyworth – Public Domain

No one knows its language or culture. Most of its inhabitants farmed. Others worked making ceramics or carving obsidian, a volcanic glass. Many merchants lived there as well. Archaeologists have found about 200 single-story apartment compounds in the ruins.

Around 750 C.E., a fire burned the central part of Teotihuacán. The fire may have been part of a civil war or rebellion. Parts of the city still functioned, but large parts had become ruins.

The Aztecs emerged as the dominant power in Central Mexico after 1300 C.E. They found Teotihuacán abandoned. They incorporated it into their cosmology. Much confusion exists about the name the Aztecs gave to the city. The Aztecs called it either “Teohuacan” (city of the sun) or “Teotihuacán” (“city of the gods” or “place where men become gods.”).

Previous attempts to stop the construction

El Pais reported that the construction company first built a fence around their proposed recreation area. Neighbors begin to notice things changing. Historian and tourist guide, Jane Kadala told El Pais that before the construction, “there were three unexplored mounds and the masons [have since] destroyed at least one.”

The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) heard in March that construction was occurring near the site. Early that month, the Archaeological Zone of Teotihuacán (ZAT: Zona Arqueológica de Teotihuacan) sent staff to the site to stop construction. They posted stop-work orders issued by INAH. The construction crew removed ZAT’s signs, ignoring the orders, and continued to work on the project.

The delays in attempting to stop the building project shine a light on how the Mexican government’s antiquated and often unwieldy legal system makes it hard to enforce building codes and zoning laws and to stop illegal construction, even on protected historical sites Teotihuacán.

Archaeologist Rivero Chong reported that they appeared to be building foundations for structures, using bulldozers to clear the ground within the fenced-in area. He said, “That made us assume that significant damage had been done in the area.”

The U.N. International Council on Monuments has also become involved. According to that Council, the bulldozers threatened 7 hectares (15 acres) at the site.

On April 20, the INAH filed a formal complaint with the Federal Public Ministry. The INAH charged damage was being done to the archaeological site. An archaeologist and officials from the Public Prosecutor’s Office went to the site. The construction crew brandishing pipes, stones, and sticks chased the INAH team away.

El Pais reported that local authorities suspect a local politician, René Monterrubio, to be the owner of the fenced-in area. In the 90s, he was chief of police in Mexico City. Monterrubio formerly was president of a nearby town, San Juan Teotihuacán. He had made campaign promises to build a large Ferris wheel in the vicinity.

INAH had received a request to build a Ferris wheel when Monterrubio was mayor. They denied the request since it would have violated UNESCO guidelines for a world heritage site.

Rivero Chong said, “We know that he is presenting himself as the owner, it will be up to the prosecution to confirm whether the private property is owned by Monterrubio.”

The Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan – Image credit: E. Scott

The village of Oztoyahualco

Archaeologists believe that the fenced-in site is the location of a settlement. That settlement, the village of Oztoyahualco, predates urban Teotihuacán and dates to 300 B.C.E. The area appears to have been the center of a rabbit cult. Babies who died at birth would be buried with rabbits in their graves.

According to archaeologists, Linda Manzanilla, and Rene Millón, 20 archaeological structures lie within the fenced-in area. One of three mounds within that area is gone already. The area also contains a cave.

Destructive tourism

One resident, Guillermo García, told El Pais that the threat is not just construction. He called it “destructive tourism.”

García said, “I feel that the new tourism in Teotihuacán is destructive. It is not regulated, nor does it follow the rules, nor does it respect the archaeological zone. There are motorcycle tours that ride on the mounds of Oztoyahualco, without knowing the richness of the site, just for fun.”

Located 50 km (30 miles) northeast of Mexico City, Teotihuacán attracts 2.6 million visitors per year. If a site so close to Mexico’s largest city and so popular can be threatened, it does not bode well for Mexico’s more remote and less popular sites.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.