ST. LOUIS – Last week, the Saint Louis Art Museum opened a new visiting exhibition, “Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa.” Drawing from the extensive Nubian collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, “Nubia” not only showcases an extraordinary collection of ancient art and artifacts but also examines the narrative surrounding ancient Egypt’s southern neighbor – including how the biases of Egyptologists led to the splendor of Nubia being overlooked for so long.

Nubia, known to the ancient Egyptians as Kush, is a region that stretches from the First Cataract of the Nile near Aswan to modern-day Khartoum in Sudan.

In ancient times, the Nubian civilization rose alongside ancient Egypt, with whom it had a complex relationship. The Egyptians had a vested interest in portraying their empire as consistently victorious over its foes, and they often depicted Nubians as subservient, conquered enemies. In truth, however, the Nubians often had the upper hand over their Egyptian rivals, and at times – such as during Egypt’s 25th dynasty – Nubians ruled over both civilizations.

Over the course of their civilization, Nubians built more pyramids than their Egyptian neighbors and had trade networks throughout Africa and the Mediterranean.

Wall inlay of a lion, Classic Kerma period, 1700 – 1550 BCE [Photo Credit: E. Scott]

“Nubia” displays over 300 artifacts from throughout ancient Nubian history, ranging from tiny amulets of gods like Ra-Horakhty to massive statues of Nubian kings. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts acquired these items in the early 20th century as part of more than 20 years of excavation in Egypt and Sudan.

The exhibit notes early on how these scientific excavations were tied into colonialism, as both countries were under British administration at the time. While the items were certainly acquired “legally,” the colonial legacy of the excavation would go on to influence how the artifacts were interpreted for decades to come.

In an interpretive video that is part of the exhibit, the Egyptologist Vanessa Davies explains that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Egyptologists felt the need to bring ancient Egypt into the sphere of Biblical scholarship. As part of this effort, ancient Egypt was separated from the rest of Africa and placed firmly into a Mediterranean or Semitic context – one where the great Egyptian civilization could be considered “white,” while the other “Black” African cultures, like Nubia, were treated as lesser, if they were considered at all.

As another interpretive video, this one from Shomarka Keita of the Smithsonian Institution, notes, this is an ahistorical mapping of modern racial divisions onto the past; there is no evidence that these ancient African civilizations conceived of race as denoted by skin color.

In order to maintain the notion of ancient Egypt as a perpetually dominant empire, scholars ignored Nubia until only the past few decades. The cost to our knowledge of the ancient world has been immense.

George Reisner, the curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts who oversaw the excavation of the Nubian city of Kerma in the early 20th Century, was so perplexed by the presence of Egyptian artifacts that he assumed the city was an Egyptian military outpost. Reisner wrote in 1918, “The native negroid race had never developed either its trade or any industry worthy of mention, and owed their cultural position to the Egyptian immigrants and to the imported Egyptian civilization.” It was inconceivable to him and his colleagues that a “Black” civilization could have attained victories over a “white” one.

Modern archeologists now understand just the opposite: the Egyptian material was, in fact, loot taken home to their capital city by victorious Nubians.

Hathor-headed crystal pendant, Napatan period, reign of Piankhy, 743-712 BCE [Boston Museum of Fine Arts]

Although the exhibit’s dedication to its own historiography is commendable, the objects themselves are the main attraction. Much of what is on display shows continuity with Egypt, with whom the Nubians shared many cultural features, including worship of many of the same gods. One of the most dazzling pieces is a crystal pendant from the eighth century BCE topped with the golden likeness of the goddess Hathor; there is a hollow space in the crystal that may have held a prayer or spell written on papyrus.

There are many other religious artifacts on display as well, including objects dedicated to deities like Isis, Horus, Ra, and especially Amen, whose worship was widespread during the period when Nubia conquered Egypt. There are also many objects dedicated to indigenous Nubian deities like the lion god Apedemak or the hunter Arensnuphis, and animal figures that may or may not be tied to those deities; one dazzling example is a faience inlay of a lion, the glaze a bright and magnetic blue.

One highlight of the collection is a reconstructed funerary bed from the Kerma period, about 1700 to 1550 BCE, presented next to a set of ivory animals that would have been inlaid in the bed’s headboard. Among these animals is the protector goddess Tawaret, depicted as a hippopotamus brandishing a knife – certainly a deity no sensible person would be willing to upset.

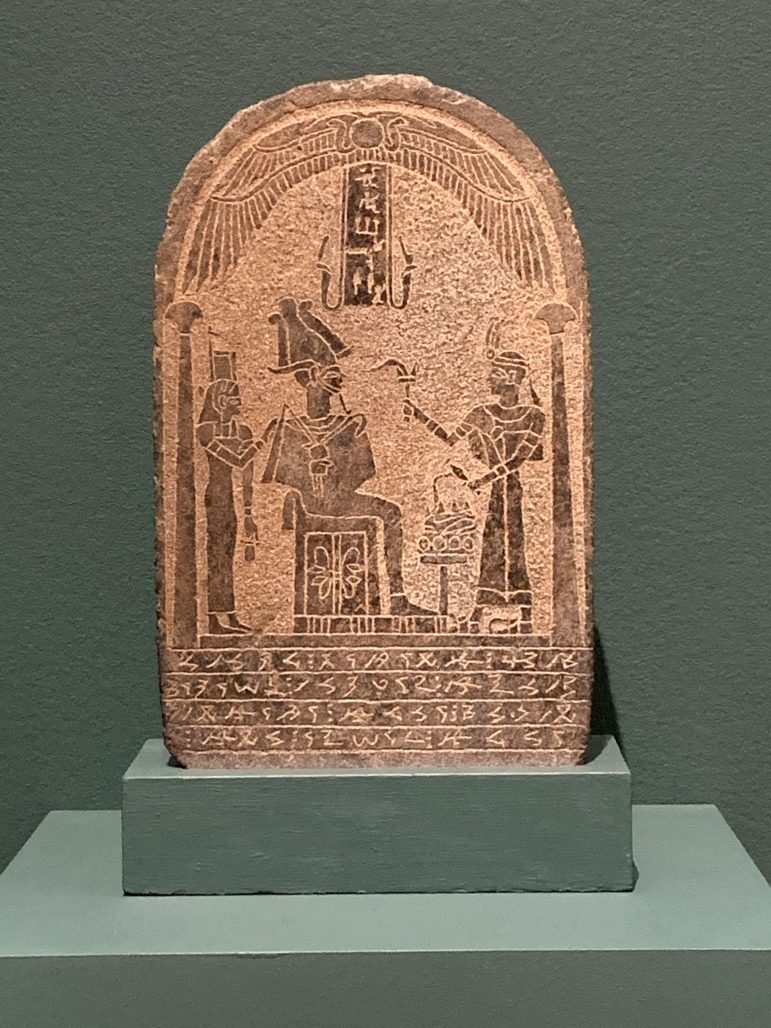

Stele of Prince Tedeken, Meriotic Period, 200 – 100 BCE [Photo Credit: E. Scott]

In addition to these depictions of the deities themselves, the exhibition features many other finds from Nubian temples and tombs, including a stele and table for offering sacrifices found in the tomb of Prince Tedeken, who lived during the Meroitic Period, between 200 and 100 BCE. Meroe, the Nubian capital during this period, was a cosmopolitan city with ingenious infrastructure and strong trade ties, but it is little understood in comparison to many of its contemporaries because scholars do not fully understand the Meroitic script. The Meroitic material, which comes at the very end of the exhibition, is some of the most fascinating in the collection – and, because we cannot read all of the inscriptions, some of the most enigmatic as well.

Even for seasoned enthusiasts of ancient Egyptian studies, “Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa” offers a welcome expansion of the ancient African world, one that invites visitors to consider a greater spectrum of contact, commerce, and conflict than has usually been presented. The curators’ willingness to examine how religious, racial, and colonial bias has harmed previous interpretation of the material is more than just a mea culpa for archeologists’ complicity in past acts of racism – it is an invitation to think through how knowledge of the ancient world comes to be, to participate in the act of interpretation that eventually decides on a historical narrative.

For those of us in the modern-day who maintain a relationship with the gods of these ancient cultures, those acts of interpretation have high stakes. It is only through constant reevaluation – like the kind on display here – that we can maintain those relationships in a just manner.

“Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa” is on display at the Saint Louis Art Museum until August 22nd.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.