I’ve spent a lot of the past week dying. Sometimes death takes me by surprise as I walk into a trap hidden somewhere in an eerie green dungeon; more often, especially in the last few days, it’s been a grim inevitability, slogging battered and penniless along the hellish banks of a river of fire. But I have become somewhat more adept at death in the past few days — the last few times I died, I made it as far as Elysium before I slipped away, back to the halls of Hades.

Hades, the video game from Supergiant Games, had an early access release in 2018 but had its official release last month for Windows, macOS, and the Nintendo Switch (which is the platform I have played it on.) It’s an action RPG, built around procedurally generated levels — which means that every time the player enters the game, the layout of the levels is different.

Part of what keeps the gameplay compelling is that the player never quite knows what enemies they will face in a given room, nor what kinds of powers they will be able to collect to defend themselves. The only thing certain is that the player will die many, many times en route to completing the game, and every death entails starting over again — a premise with a long history in computer games, dating back to games like 1980’s Rogue, a game so wizened that it used ASCII characters in place of graphics.

While I have long been a fan of “roguelike” games — I dabbled in the totally inscrutable Nethack in my teens and was fixated on FTL: Faster than Light for years — Hades drew me in because of its setting: rather than playing as a nameless adventurer dropped into a dungeon, Hades puts players in control of Zagreus, the son of Hades, as he attempts to escape from the underworld. At first, it seems Zagreus is simply bored of the underworld, but as the player progresses in the game — which means dying over and over (and over) again — it becomes clear that his drive to escape from his father’s domain is more complicated than it appears.

Zagreus bickers with his father Hades [Supergiant Games]

Hades is not a straight read on Greek mythology, but the way it toys with the myths is a delight. Take, for example, its approach to Elysium, which serves as the game’s third level. At first, Elysium seems like a poor setting for an action game — aren’t these the Blessed Isles where heroes go to spend eternity in paradise? But Zagreus finds himself bedeviled by the shades of Elysian warriors precisely because Elysium is filled with the spirits of heroes — people who, in the classical understanding, were certainly accomplished, but not necessarily very nice. (Patroclus, the lover of Achilles, finds himself miserable in Elysium precisely because he has no desire to fight endless battles.)

As the name implies, Hades puts the spotlight on the Chthonic deities of Greek myth. While the more well-known Olympian gods do appear throughout the game as sources of new abilities for Zagreus, the player spends more time with deities like Hypnos, Thanatos, Nyx, and the Erinyes, all of whom reveal more of the personalities to the player over the course of the game. Zagreus himself is based on an obscure underworld god sometimes identified with Dionysos, though they are separate entities in the game.

Hades himself, the god of death, is technically the game’s antagonist, but he gets a fairer shake here than in most adaptations. He is presented as a stern, often harsh, and always distant father to Zagreus, but also as a dutiful ruler of the underworld who puts its administration above his own happiness. Although he is the one who refuses to let Zagreus leave for the surface, he is available for conversations just as much as anyone else in his household and their relationship is less a battle between good and evil than a troubled and complicated relationship between parent and child.

One might ask, what about Zagreus’s mother? Where is Persephone? That question is one of the game’s key mysteries, and learning the answer is a major reason for the player to continue their attempts to escape from Hades.

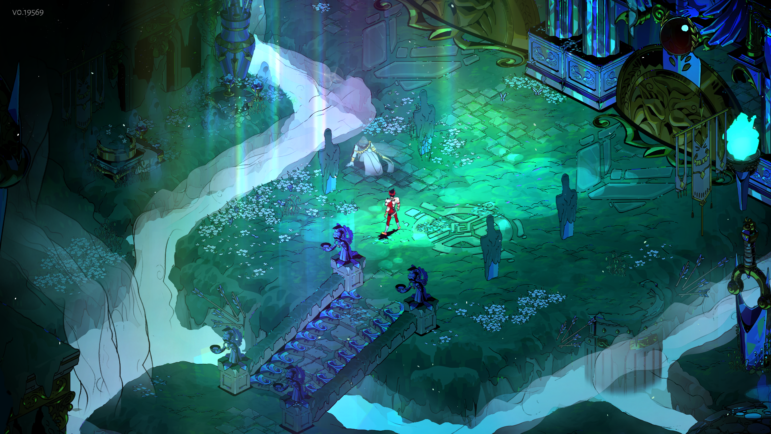

Zagreus enjoys a brief moment of peace in Elysium [Supergiant Games]

As for the game itself, Supergiant Games has done a tremendous job of making a game that provides a nearly endless variety of play, yet has a steady learning curve that rewards the attentive player. Challenges that swiftly end a player’s early attempts become only slight obstacles with practice, and new combinations of weapons, power-ups, and abilities present themselves in every new run. And because the story of Zagreus and his family reveals itself little by little with every try, the player is always itching to do “just one more run.”

Generally, we think of “story” in video games as a linear plot, like a film or a novel, where a character travels through events from beginning to end. Sometimes games have experimented with other ways of creating narrative — FTL, for example, let the random events it threw at the player create an emergent narrative, trusting the player’s imagination to sew a story together. Hades has managed to take the nature of its repeated loop and turn it into a vehicle for a story that weaves itself together over dozens of playthroughs. In the process, it has created one of the most vivid explorations of Greek mythology yet seen in video games.

For now, though, please excuse me — I just unlocked a new form for Varatha, the Eternal Spear, and I can’t wait to take it on a new run through Tartarus.

The Wild Hunt is not responsible for links to external content.

To join a conversation on this post:

Visit our The Wild Hunt subreddit! Point your favorite browser to https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Wild_Hunt_News/, then click “JOIN”. Make sure to click the bell, too, to be notified of new articles posted to our subreddit.